With no end in sight to Sudan’s civil war between its army and a breakaway paramilitary group, and efforts to facilitate peace talks frustrated, analysts now suggest that the fight will come down to each side’s control of resources, suggesting that the winner will be the one able to command the necessities for an economy.

The war between the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF), based in Port Sudan in the east, and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), based in Darfur in the west, is now in its third year, with no prospect for a peaceful solution, after efforts by states including the US, Saudi Arabia, and Egypt drew a blank.

The two foes now seek international recognition and have both sought to establish a ‘government’ in recent weeks, to confer a sense of legitimacy, despite the fighting having precipitated perhaps the world’s worst humanitarian crisis, with widespread reports of war crimes on all sides. “In Sudan’s war, legitimacy and resources are two sides of the same coin,” said Andreas Krieg, a senior lecturer at the School of Security Studies at King's College London, speaking to Al Majalla.

“Neither the SAF nor the RSF can credibly sustain a government without controlling the resources that fund the war effort, feed populations, and underpin patronage networks. In practical terms, whoever can point to a functioning economy—whether through oil exports, gold sales, agricultural surpluses or customs revenues—will have a stronger case for governance.”

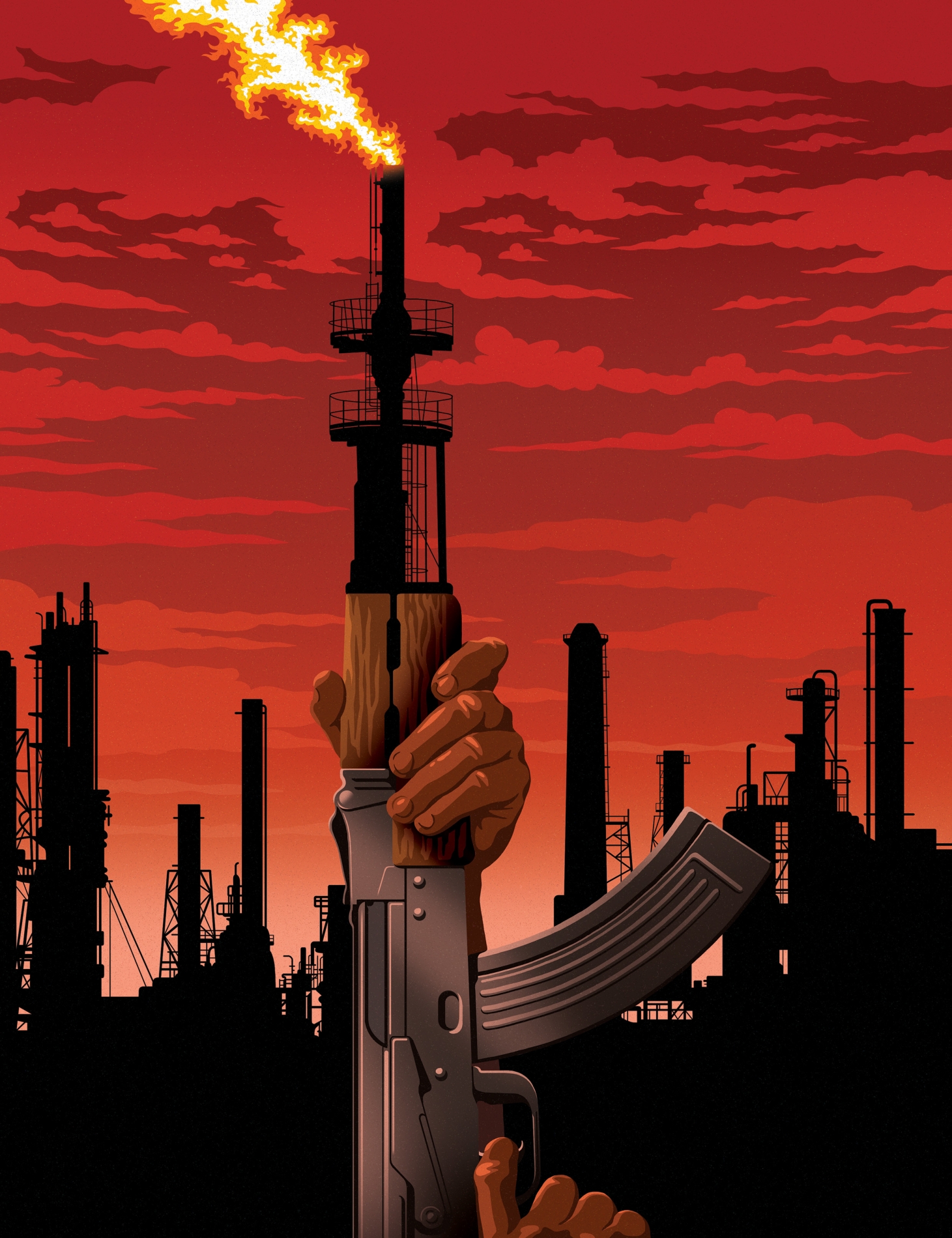

Controlling resources

The SAF controls the vital Red Sea coast, huge tracts of agricultural land, oil transport infrastructure, hydropower dams (which generate most of Sudan’s power), and has the capital Khartoum. In Darfur and Kordofan, the RSF controls most of Sudan’s gold, its livestock grazing lands, and Gum Arabic—a substance harvested from acacia trees that is used to make beverages (Sudan supplies nearly 80% of the world’s Gum Arabic).

“From a purely economic standpoint, the RSF sits atop the country’s most valuable raw assets, while the SAF holds the ports, institutions, and infrastructure that would let those assets reach international markets,” said Krieg. Both army chief Abdel Fattah al-Burhan and RSF commander Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo (known as Hemedti) are fighting over Sudan’s oil supplies. A victory for either side over this crucial resource could prove decisive in the confrontation.

Krieg cautioned that although “recognition depends as much on legitimacy, conduct, and international law as it does on resource control, in the event of a long stalemate, oil would be a powerful tool for the faction that holds it to present itself as the functional government of Sudan,” adding: “At present, international legitimacy still rests with the SAF, which holds Sudan’s formal seat at the UN and retains the appearance of a state apparatus.”

Arguably, the SAF has received more support than the RSF. Iran gave arms and drones at a time when the RSF was winning territory in Africa’s third-largest country. China and Russia have also built relations with the SAF. Moscow, which wants a naval base on Sudan’s Red Sea coast, has given the SAF fuel, weapons, and equipment. Regional powers, including Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Türkiye, and Egypt, have also stood behind Burhan. A Saudi delegation visited Port Sudan in March, vowing to help in the reconstruction effort. That month, the SAF wrested back Khartoum and Gezira, the latter being the country’s central farming hub.