In el-Fasher, the sky seemed to collapse upon the weary shoulders of a city long strangled by siege, as the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) flung open the gates of hell on 26 October, unleashing terror on those clinging to life like. The level of violence has reshaped the civil war in Sudan. Many now wonder whether the state itself will survive.

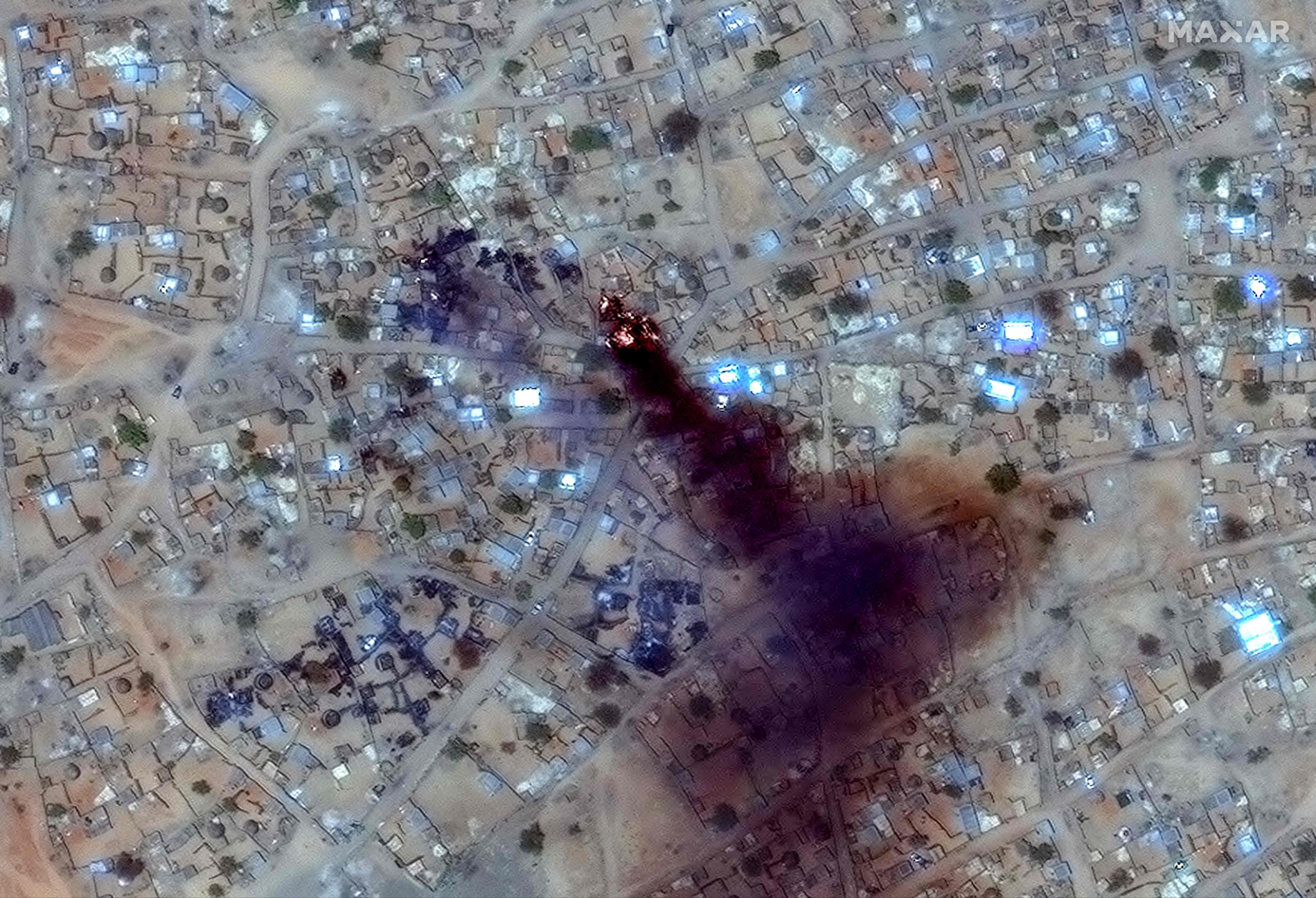

El-Fasher is the capital of North Darfur and the last holdout of the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) in western Darfur, a landlocked, mineral-rich area the size of Spain. It fell to the RSF after more than 500 days under siege. By the end of October, the city’s population of 1.5 million (as recorded in May 2024) had shrunk to around 250,000. Many of these were internally displaced and close to starvation, surviving on livestock fodder. As satellite images showed, the RSF built a 57km earthen barrier encircling the city, sealing it off entirely.

A coalition of army units, joint forces from Darfuri armed movements, and local popular resistance fighters had mounted the 500-day defence of el-Fasher. In their minds was the RSF’s genocidal rampage through El Geneina, capital of West Darfur, at the war’s outset. In April, the RSF stormed the Kalma camp for displaced persons. Drone struck hospitals, mosques, and homes. More than 260 ground assaults were launched in attempts to breach el-Fasher.

In the end, starvation was used as a weapon, until 26 October, when the RSF launched a massive offensive against the Sixth Infantry Division, the army’s last remaining base in Darfur. After fierce combat, the RSF seized the base, deploying advanced Chinese-made drones, hundreds of foreign mercenaries, and a sophisticated Chinese jamming system capable of disabling Starlink communications. The use of such technology by a non-state actor alarmed regional observers.

A tale of horror

Having breached the city’s gates, the RSF began massacring civilians. According to the World Health Organisation, more than 460 patients and staff were killed inside the Saudi Maternity Hospital alone. RSF fighters posted videos on social media showing them stepping over piles of corpses and shooting survivors at point-blank range. No-one was spared—not the sick, nor their caretakers. Up to 2,000 people are thought to have been killed in the hours after the city’s collapse.

The International Organisation for Migration estimated that around 62,000 people fled el-Fasher from 26-29 October, most of them on foot, heading towards the town of Tawila, 70 km away. Along the way, they faced extortion, sexual violence, and brutal assaults. A much smaller number are thought to have made it to the town, but reliable statistics are hard to come by.

Yale University's Humanitarian Research Lab observed body-disposal activities between 25 October and 13 November 2025 at four locations within el-Fasher. Two sites—el-Fasher University and Saudi Hospital—are reported by Sudan Tribune to serve as two of five RSF detention centres identified, according to those arriving in Tawilah. More than 50,000 people are believed to be detained by the RSF.

Among the atrocities and perpetrators, one name recurs: that or Fath al-Rahman Abdullah Idris, known as Abu Lulu. The most notorious of RSF's field commanders, he is unwaveringly loyal to the RSF's military leader, Abdelrahim Dagalo. Abu Lulu is known for his extreme brutality against civilians, orchestrating massacres and looting. He regularly flaunts his atrocities on social media. This is not just sadism; it is psychological warfare, designed to instil terror, crush resistance, and reinforce the idea of racial supremacy that is at the root of this conflict.