Among the more exciting prospects in the world of nuclear energy is the use of thorium metal, and technological breakthroughs in the field have focused attention on the world’s deposit distribution.

Nuclear reactors currently use the uranium-233 isotope to create energy. This is a ‘fissile’ material, meaning that it can split (a process called nuclear fission) when bombarded with neutrons. That releases the energy that powers homes and industry. Thorium-232, by contrast, is a ‘fertile’ material, meaning that it can become uranium-233 when showered with neutrons. Since thorium is much more plentiful than uranium, investors are taking note of the science.

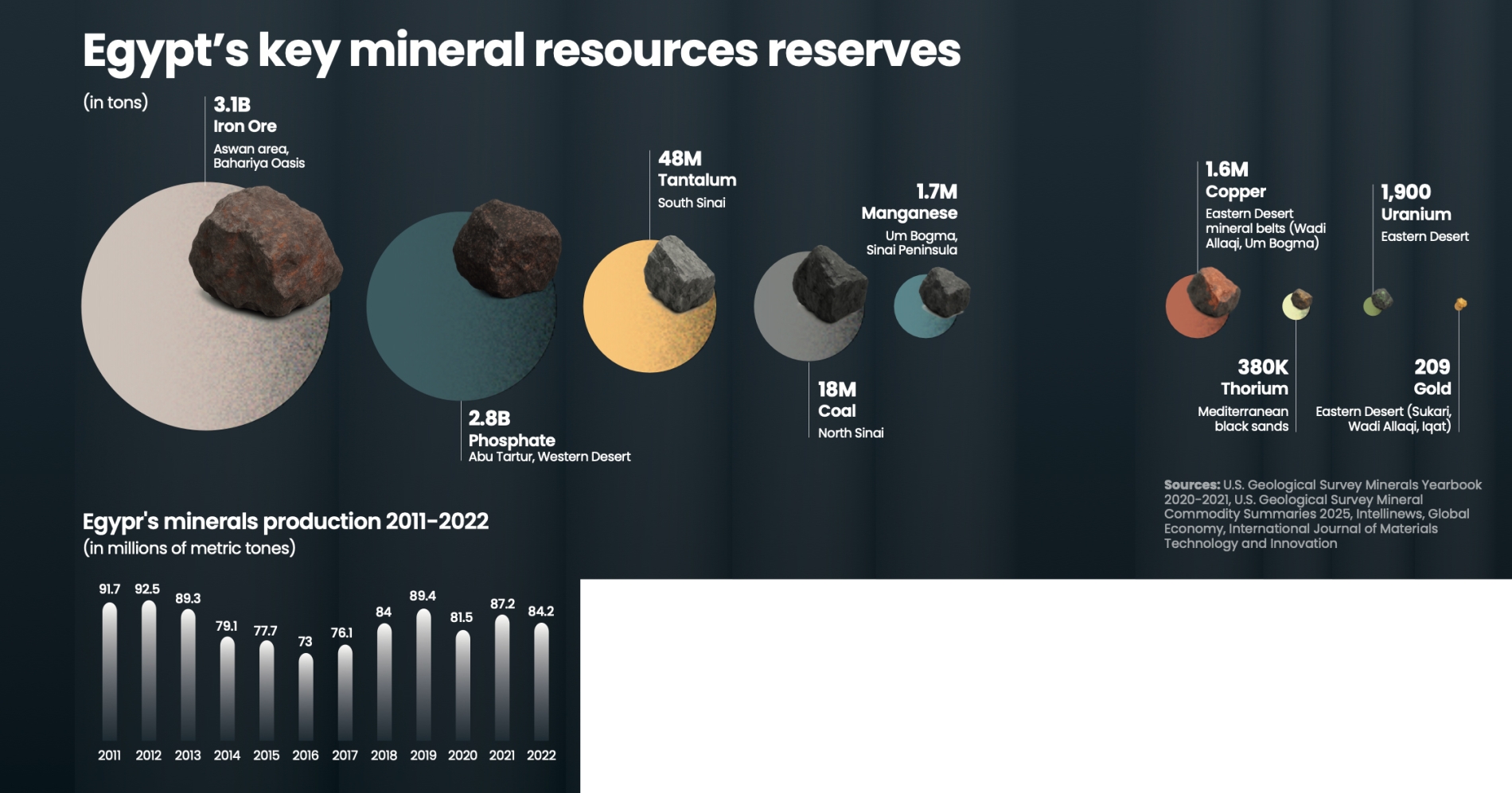

The largest reserves of thorium are to be found in India, Brazil, the United States, Australia, and China, but Egypt ranks sixth worldwide with reserves of around 380,000 tonnes. If thorium emerges as a key future energy resource, these reserves found particularly in the black sands of its northern coast could quickly become strategic, opening the prospect of mineral exports to become a crucial revenue source. Some believe Egypt could develop an integrated nuclear infrastructure to harness its thorium, thereby helping the country meet its domestic energy needs.

Strong potential

Thorium is considered cleaner and safer than traditional uranium because a thorium fuel cycle produces less long-lived waste and offers increased safety margins in reactors. This has sparked interest from the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) and the Nuclear Energy Agency (NEA) of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). It has also generated interest in Cairo.

Stretching from Alexandria to Arish along a 400km coastline, Egypt’s northern sands are rich in minerals such as zircon, tantalite, monazite, ilmenite, and rutile, which are used in industries such as aviation, rockets, automotives, electronics, ceramics, and paint. Egypt’s new Minerals Law gives the state the legal power and tools to exploit these resources, an ongoing process that began in 2016, when the government created the Egyptian Black Sand Company in partnership with the Egyptian Nuclear Materials Authority and the National Service Projects Organisation.

In the Burullus region of the Kafr El Sheikh governorate, swampland was transformed into large-scale industrial facilities using technology from Australia and China. A mineral separation plant spanning 324,000 square metres began operating, and a giant electric-powered Dutch dredge weighing 550 tonnes began extracting black sand at a rate of 2,500 tonnes per hour. A second 142,000 square metre mineral separation site in the western Burullus soon followed, bringing jobs, skills, and investment.

It demonstrates the country's hopes for its mining industry, in which thorium could play a leading role if the technology moves from experimentation to the operation of thorium-fuelled reactors. These reactors are highly specialised, expensive, and still under construction. They also remain the subject of scientific research.