What lies beneath the ground in Algeria has long been of interest economically, but for decades, all anyone thought about was oil and gas. Lately, however, there has been interest in the country’s other subterranean assets, the mining of which is soon expected to be a key driver of economic diversification.

Since taking office in 2019, Algerian President Abdelmadjid Tebboune has prioritised this sector, harbouring ambitious hopes. But a controversial new minerals law has divided opinion, with some fearing a reversion to a rentier economic model. Supporters see it as a catalyst for investment, while critics say it surrenders sovereignty.

How Algeria reconciles economic openness with the protection of its natural resources is now a key question, given its vast potential resources and growing external interest.

Subterranean riches

One of the first big discoveries was in 2015, when—with Japanese help—selenium was found in parts of the city of Sig in western Algeria. Selenium is in high demand due to its use in the electronics industry, photovoltaic solar panels, and pharmaceuticals.

A further key element found in Algeria is lithium, which is used to make lithium-ion batteries for electric vehicles (EVs) and mobile phones. Algerian Energy Minister Mohamed Arkab is among those to see great potential in this field, noting its presence in the country’s south, where he said there were “ideal geological characteristics for mineral extraction”.

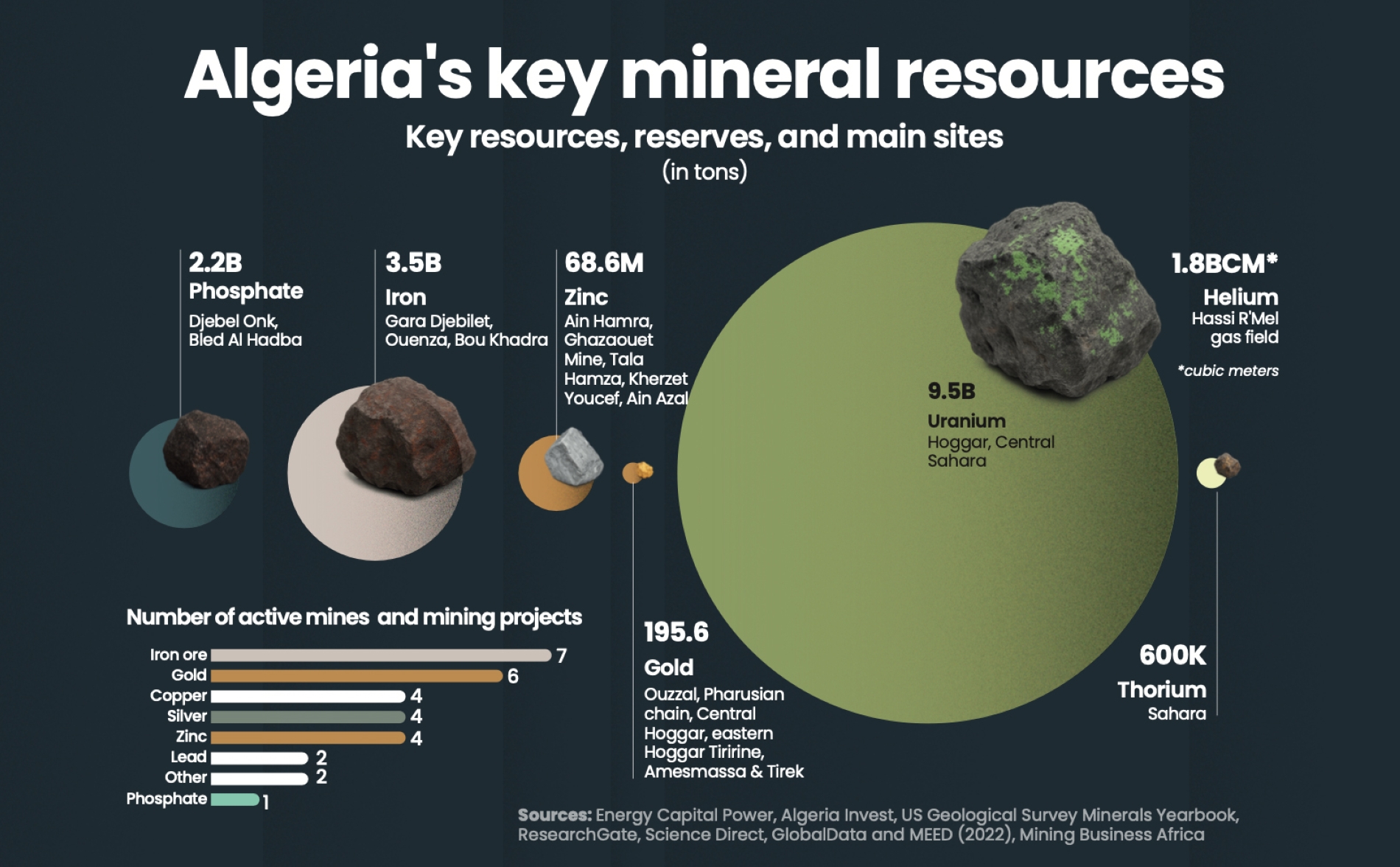

Another big mining focus is Algeria’s phosphate reserves, which are estimated at around 2.2 billion tonnes, among the largest in the world (although dwarfed by neighbouring Morocco’s 50 billion tonnes). Most of Algeria’s phosphates are concentrated in the country’s north-east.

Bled El-Hadba mine, south of Tebessa province, is one of the most important phosphate development projects. With an estimated investment of around $7bn, it is hoped that the mine will establish Algeria as a leading producer and exporter of fertilisers once completed.

Likewise, the Ghar Djebilet iron ore mine in south-western Algeria is one of the largest in the world, with reserves of 3.5 billion tonnes. It officially opened in July 2022, and annual revenues are expected to eventually reach around $10bn.

Helium is another important resource in Algeria’s mineral portfolio. According to some estimates, the country holds the world’s second-largest reserves after the United States, amounting to 1,800 million cubic metres. These reserves are concentrated in the Hassi R’mel region of the Algerian desert.

Widespread concern

With ongoing efforts to leverage Algeria’s mineral resources, concerns have been expressed by academics, economists, researchers, and politicians that the minerals sector could become a new rentier economy i.e. one in which a significant portion of income is derived from the ownership of assets like land, natural resources, or financial capital, rather than from productive activities like manufacturing or services.

This has been seen with Algeria’s oil and gas over the past two decades, leading to excessive dependence on hydrocarbons (around 90% of Algeria’s exports are hydrocarbons, and this accounts for almost half of government income).