For thousands of years, metals have been linked to human advancement, from Stone Age tools made of flint to the iron that fired the factories that powered the Industrial Revolution. Today, these natural resources are no less important; their access and exploitation fuel geopolitical and economic conflict. From lithium and cobalt to uranium and titanium, rare metals are no longer just raw materials but the keys to controlling technology, clean energy, and national security.

In this article, Al Majalla delves deeper into this fight for precious minerals, learning what they are, where they are, and what they power or enable. Often referred to as ‘rare earth’, a group of 17 chemical elements, such as neodymium and dysprosium, are increasingly the backbone of modern industries, used in everything from smartphones and electric vehicles (EVs) to wind turbines and advanced weaponry.

Although rare earth elements are abundant in the Earth’s crust and geological deposits, extracting them is costly and complex, owing to their dispersion and their cellular entanglement with other metals. Moreover, rare earth extraction poses significant environmental challenges because the process can generate toxic waste that contaminates water sources and soil, while the more traditional extraction of iron, copper, phosphates, and lead is still essential for infrastructure and heavy industries.

Mineral distribution

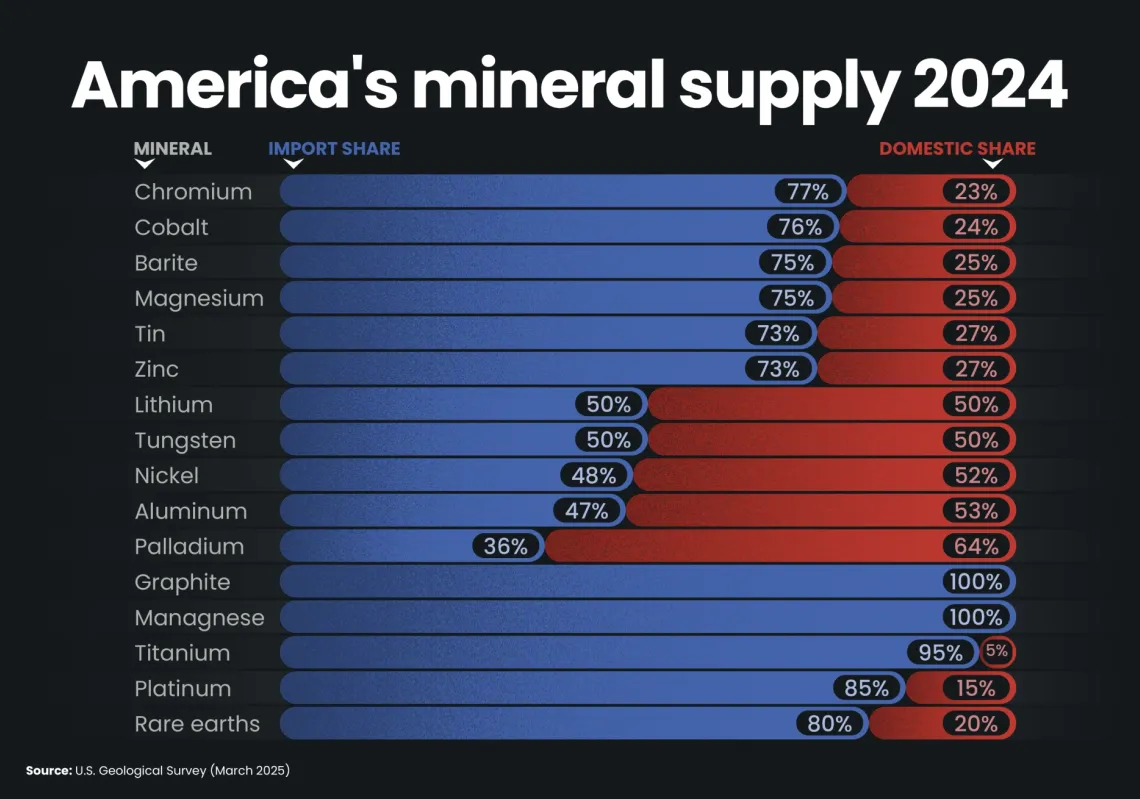

Strategic metals are concentrated in specific parts of the world, with China controlling 60% of rare earth element production. The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) holds 70% of the world’s cobalt, for example, while Australia has half of the world’s lithium. These distribution hotspots lead developed nations to compete for supplies, as do technological advances. The shift towards clean energy, for instance, has led to a fourfold increase in demand for the elements needed in battery storage, according to reports from the International Energy Agency.

Countries use their rare earth resources as a tool for political pressure. In 2010, for example, China restricted its exports to Japan during a diplomatic dispute over the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands in the East China Sea. Further restrictions are placed on metals used in the production of advanced weaponry.

From Congolese mines to Arctic ice, rare resources lead to competition and conflict, as nations fight to control the minerals needed for strategic industries. Of all the continents, Africa is among the most resource-rich, with vast reserves of cobalt, lithium, and uranium. Foreign powers, from Israel to China, vie for control of cobalt mines; likewise, the Birimian Greenstone Belt in West Africa—rich in gold, bauxite, lithium, manganese, nickel, phosphates, and zinc—represents another flashpoint.

Rare earth flashpoints

It is no coincidence that US President Donald Trump has set his eyes on Greenland (an autonomous Danish island). This territory is home to rare earth elements like neodymium and graphite. The European Commission has identified 25 of 34 “critical raw materials” as being present in Greenland, explaining Trump’s interest.

The disputed islands of the South China Sea also contain rare earth element deposits, as does the Arctic, which is considered a sphere of influence by Russia, Canada, and the United States, all competing for the valuable deposits beneath the ice.

Another key country when it comes to rare earths is Ukraine, which has huge reserves of lithium, titanium, and graphite—all vital for several advanced industries. These resources are concentrated in eastern Ukraine, which is where Russian occupation forces have focused their efforts.

Similarly, in South America, Colombian mines containing gold, coal, uranium (to name but three) have been the source of conflict between government forces clash with non-state armed groups, while in Peru and Ecuador, resources such as gold, silver, copper (demand for which is set to rise by 50% by 2040) are also fought over.