In his inaugural speech in January, Lebanese President Joseph Aoun stated that the Lebanese state should regain its monopoly over the use of force, which was met with applause from lawmakers and international partners alike. A former Lebanese army commander, Aoun, repeated that pledge in April. A decision “has been taken,” he said.

Until it becomes clear when and how this goal will be achieved, everything in Lebanon will be put on hold. The United States, France, and Saudi Arabia will not help reboot Lebanon’s debt-stricken economy or wade into the reconstruction task in the south until Aoun and Prime Minister Nawaf Salam present a concrete blueprint for disarming Hezbollah.

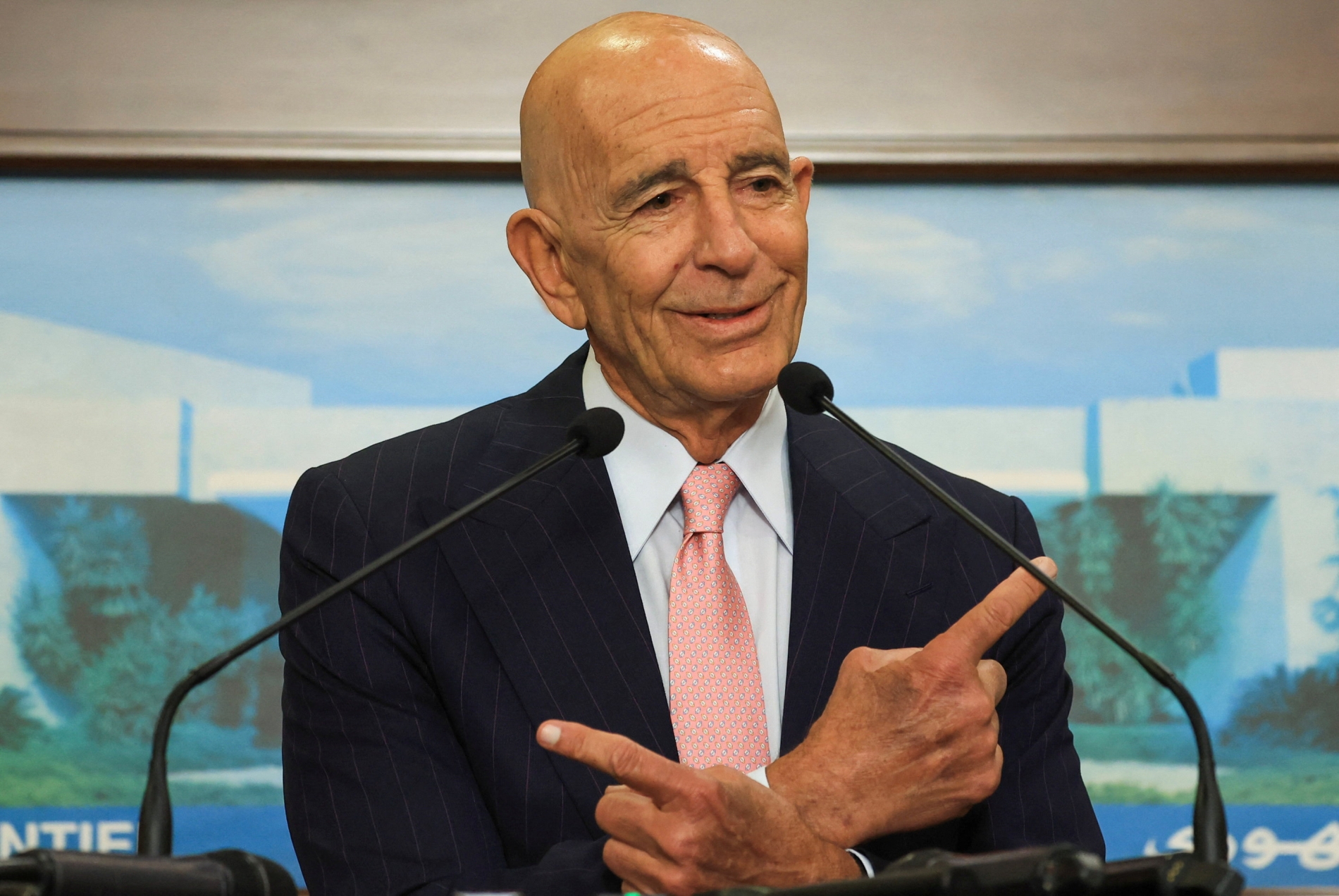

Washington wants there to be a public commitment from Beirut. If this doesn't happen, US special envoy Tom Barrack could end his shuttle diplomacy, which could mean Israel feeling less pressure to end its airstrikes and pull its troops away from the five hilltops it is occupying in southern Lebanon.

Israel is believed to have destroyed most of Hezbollah's arms, but the Iran-backed group reportedly still has weapons stored north of the Litani River, the Bekaa Valley, and the southern suburbs of Beirut, including armed drones and long-range precision-guided missiles. What it still has, it will keep, says leader Naim Qassem, who succeeded Hassan Nasrallah after Israel killed him in September 2024. “We will not surrender or give up to Israel,” he said in a video message on 18 July. “Israel will not take our weapons away from us.”

Qassem’s words should shock no one: Hezbollah was always unlikely to disarm voluntarily and transition to a ‘normal’ political party, since this would mean ‘throwing in the towel.’ Surrender is antithetical to the group’s philosophy of armed struggle and martyrdom. Without its guns, Hezbollah is just another sectarian group in Lebanon—only with less political acumen and experience than others.

Yet despite Qassem’s declarations, the Lebanese cabinet met on 5 August to discuss the issue of Hezbollah’s disarmament, with Salam saying after the meeting that ministers approved the “objectives” of a US proposal for “ensuring that the possession of weapons is restricted solely to the state”. Hezbollah ministers and Shiite allies in the Lebanese cabinet withdrew from the meeting in protest. They called the decision a “grave sin” and vowed to act “as if it did not exist.”

For his part, Head of Loyalty to Resistance bloc Member of Parliament Mohammad Raad stressed shortly after the meeting that the Lebanese government's decision to disarm Hezbollah was being imposed by foreign dictates and not in line with the spirit of the national pact and sovereignty. Ali Akbar Velayati, an adviser to Iranian Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khamenei, added to Raad’s comments, saying on 9 August that Tehran is opposed to Hezbollah's disarmament. This prompted a response from the Lebanese government, which called Velayati’s comments a “flagrant and unacceptable interference” in the country’s internal affairs.

At the time, Barrack, the US special envoy, congratulated Lebanese leaders “for making the historic, bold, and correct decision to begin fully implementing” the ceasefire deal. “This week’s cabinet resolutions finally put into motion the ‘One Nation, One Army’ solution for Lebanon,” he said. “We stand behind the Lebanese people.”

Read more: Lebanon at a crossroads over Hezbollah arms

Given that Hezbollah has no intention of disarming unless forced to, and given that it may even seek to replenish its destroyed and depleted stockpiles, there seem to be two remaining options: either Israel finishes the job militarily, or else the Lebanese army steps in. Each comes with risks and complications.

The Israeli option

Israel has already carried out more than 500 airstrikes against Hezbollah targets since the November 2024 ceasefire to further degrade the group’s military capabilities and lower the chance of rearming. According to the Israeli military, it has killed at least 230 Hezbollah operatives and destroyed more than 90 rocket launchers and thousands of rockets, 20 command centres, 40 weapon depots, and five arms production sites, alongside other infrastructure.

Whether this continues or escalates remains to be seen. When asked, Barrack said a new Israeli war was not expected but cautioned that the US could not “compel” Israel to do anything. By sticking to its current formula, Israel can further dent Hezbollah’s remaining combat power but cannot eliminate it entirely. To do that would require another ground invasion.

The political and military costs of this may seem less tempting in Tel Aviv, where Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu is already under tremendous pressure for his disastrous handling of the war in Gaza. Invading Lebanon may divert attention from his problems temporarily, but it would also further isolate Israel at a time when states such as the UK, France, Canada, and Saudi Arabia are running out of patience.

The in-house option

The second option, then, is the Lebanese Armed Forces (LAF) helping to push Hezbollah to disarm. In a press conference following the 7 August cabinet meeting, Lebanese Information Minister Paul Morcos said that the decision to disarm Hezbollah would be implemented in accordance with a plan to be submitted by the Lebanese army by the end of August, which will include a timeline for disarmament by the end of 2025.

The plan has four phases. The first requires the Lebanese government to issue a decree within 15 days committing to Hezbollah’s full disarmament by 31 December 2025. In this phase, Israel would also cease ground, air and sea military operations.