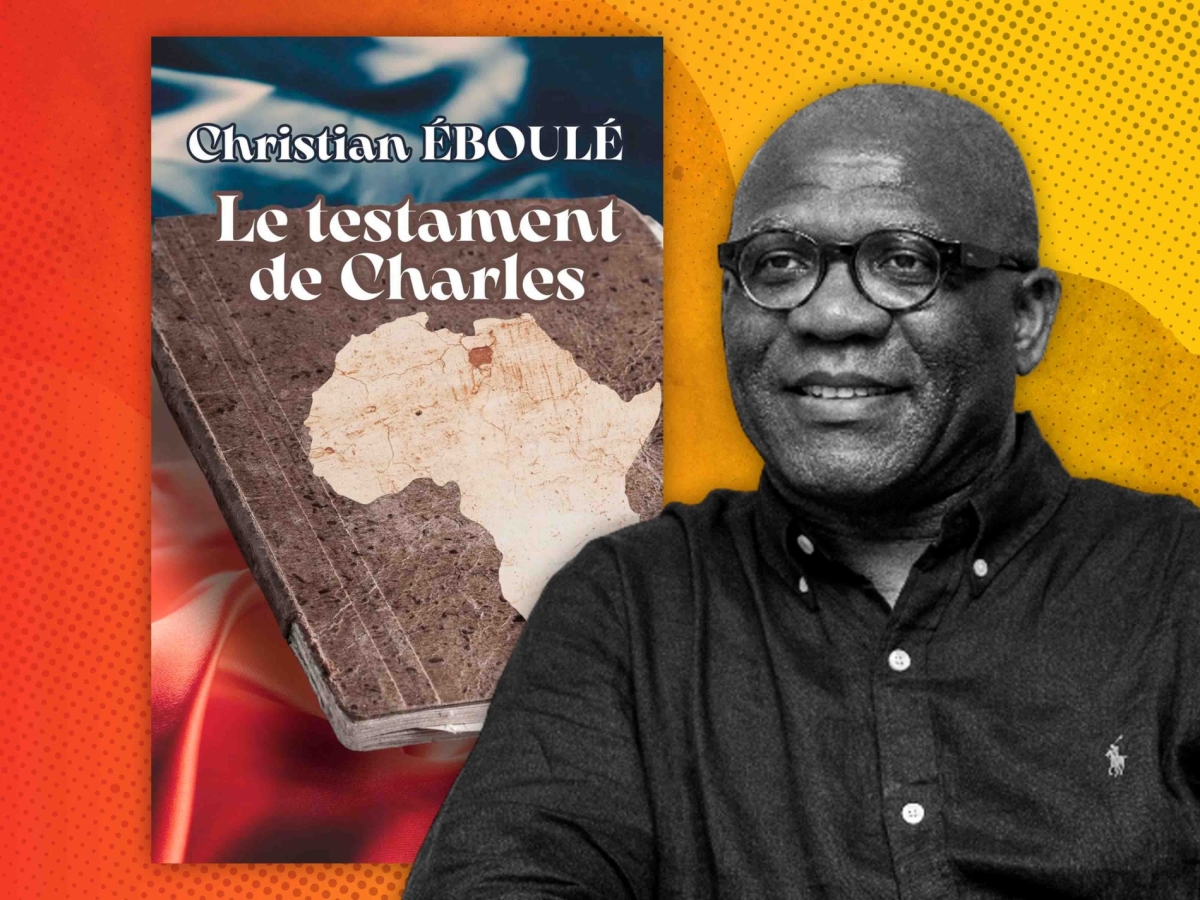

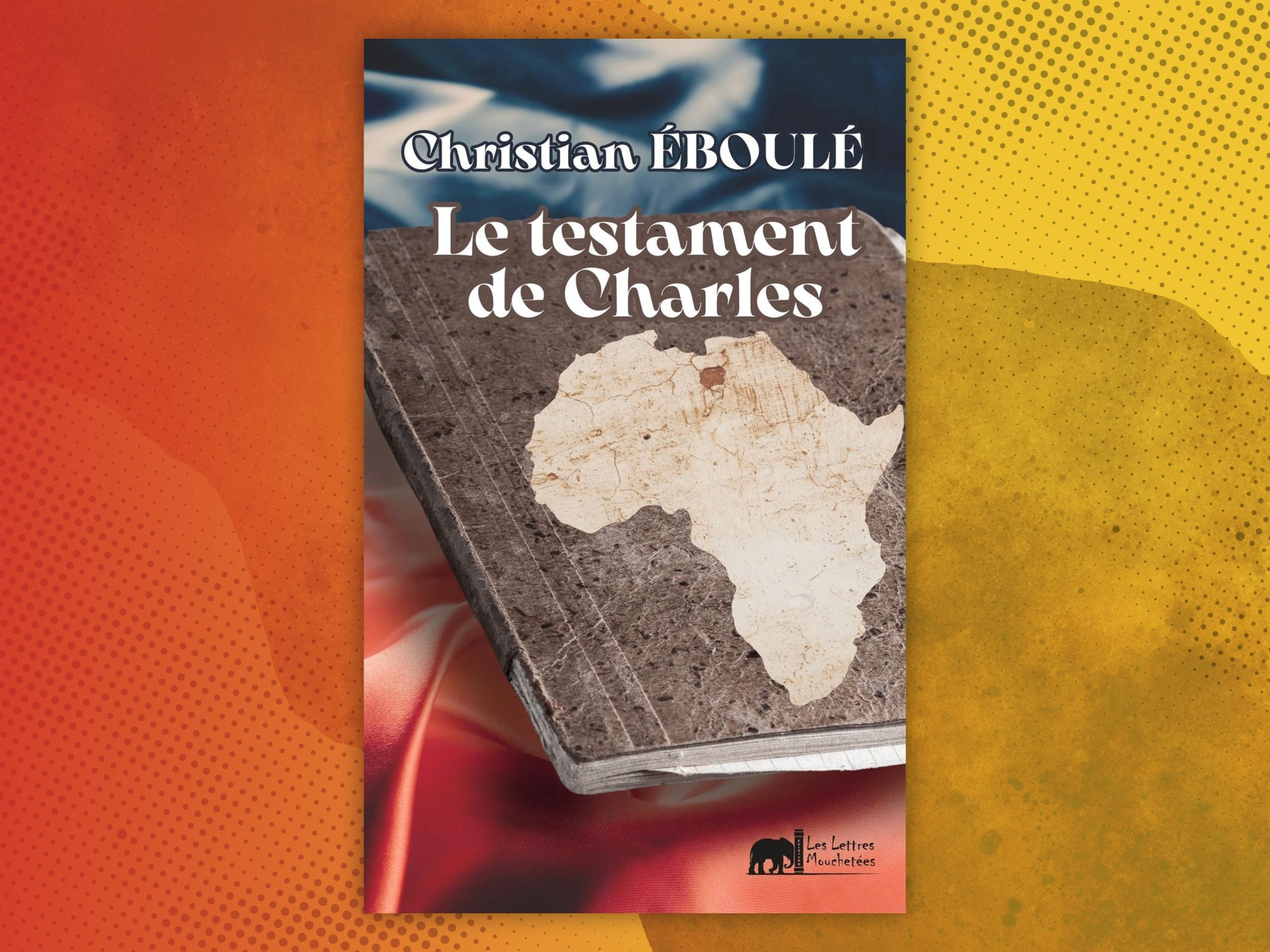

Cameroonian journalist Christian Éboulé incorporates the tragic true story of Captain Charles N’Tchoréré—a black Gabonese officer executed by the Nazis in 1940 alongside his Senegalese tirailleur troops—for his debut novel.

Le Testament de Charles, published by Les Lettres Mouchetées, draws on years of archival research across Gabon, France, and West-Central Africa, with Éboulé crafting a narrative that blends unflinching historical fidelity with existential lucidity. Al Majalla spoke to him about his novel and the legacy of colonial violence.

Several critics have described Le Testament de Charles as an act of resurrection, restoring forgotten historical figures, particularly African soldiers in the First and Second World Wars. What drew you to this neglected chapter of history?

At the end of 2009, I was deeply struck by the story of Captain Charles N’Tchoréré. His existence was revealed to me by a Gabonese friend who asked me to help him write a book about his life. This project took me to Libreville, Gabon, in 2010, where Marcel Robert Tchoreret, the captain’s nephew and president of the Captain Charles N’Tchoréré Foundation, asked me to assume sole responsibility for keeping his uncle’s memory alive. Along the way, I discovered the history of the African riflemen who fought during the world wars and the man who gave them a voice during the interwar period.

Beyond the captain’s story resonating deeply with me, the encouragement of my wife and many friends led me to help make this often-forgotten chapter of our collective memory better known.

The novel opens with Charles's death. Why did you choose this as your narrative starting point?

The novel opens with the inevitability of Charles’s death, his final moments before being murdered—in violation of the laws of war—by the Nazis who had just taken him prisoner, along with the men who remained under his command. Carried by a sudden awakening of consciousness, Charles does not merely relive his life; he also illuminates it with a harsh light, that of this new awareness, which grants him a kind of heightened lucidity, right up to the moment of his death.

Why does the colonial past remain such an open and sensitive wound across so much of Africa today?

Across the continent, many chapters of colonial history still need to be written, popularised, and democratically disseminated through almost all forms of art, so that the majority of people can truly take ownership of them. To this must be added the necessary decolonisation of minds—an essential prerequisite for overcoming alienation and healing wounds that are sometimes still wide open in our societies.