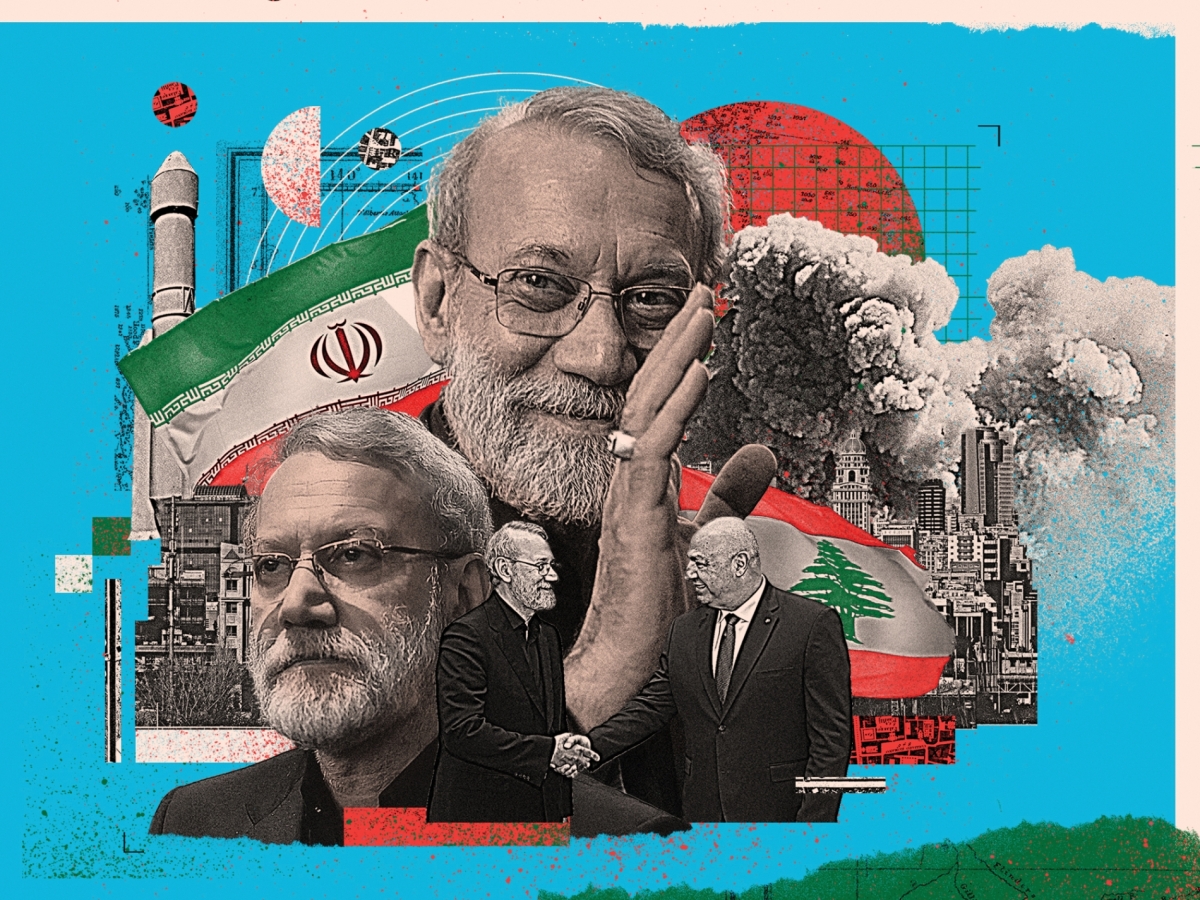

For the first time since the 12 Day War with Israel and the US, Iran has made notable changes in its security leadership. On 7 August, Ali Larijani was appointed by Iran’s President Masoud Pezeshkian as the country’s new national security advisor, replacing Ali Akbar Ahmadian. Larijani was simultaneously appointed as one of the two representatives of Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei on the Supreme National Security Council (SNSC).

Khamenei has also unveiled a new Defence Council, which has confused many since the constitution doesn’t provide for it. It does provide for subsidiary bodies under the SNSC, but only if the parliament creates them.

The Defence Council is a curious creation since it shares most of its members with the SNSC. Both are headed by the president and include high-ranking political and military leaders of the country. Both have two representatives appointed by the Supreme Leader.

To the new Defence Council, Khamenei has appointed Ahmadian and powerful former national security advisor Ali Shamkhani as his representatives. Amongst the wealthiest and powerful men in Iran, Shamkhani already led the nuclear crisis file. His appointment shows he has loyalties at the top.

The changes indicate the continuation of a process that has gone on steadily since last year: the hardliners lose power while the more pragmatic sections of the establishment—who advocate negotiating with the West—come to the fore.

Important comeback

This counts as an important comeback for Larijani—a scion of a powerful clerical family which had been relatively sidelined in recent years. In 2021 and 2024, Larijani was barred by the vetting body, the Guardian Council, from running for president. His brother, Sadeq Larijani, found his own enemies in the hardline establishment, lost his seat on the Guardian Council in 2021 and in the Assembly of Experts in 2024 (he still heads the Expediency Council).

Long ago, Larijani was counted as part of the conservative establishment, but, since he clashed with the hardliner President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad in 2007, he gradually joined a growing number of conservatives who opposed the hardliners and advocated for pragmatic policies. Larijani affirmed this position by his support for President Hassan Rouhani and his signature policy of nuclear negotiations with the West. This made him a bête noire of hardliners who relished his sidelining.

But it is now the hardliners who find themselves on the defensive. By 2023, it appeared that they controlled all major institutions of the Islamic Republic, effectively ending the government's usually lively factional life. With the mass protests of 2022-23 suppressed by the security forces, hardliners seemed firmly in charge.

But since hardliner president Ebrahim Raisi died in a mysterious helicopter crash last year, hardliners have lost battle after battle despite many of their policies being seemingly in line with the regime’s powerful leader, Ali Khamenei. Their candidate, Saeed Jalili, lost badly in the presidential elections last year to Pezeshkian.

Larijani’s return was in the making for a while. In recent years, he has served as an advisor to Khamenei and made ad-hoc high-profile diplomatic trips on behalf of Iran, including an impromptu visit to Moscow last month and to Beirut on Wednesday, 13 August. But his appointment to this key position puts him in a powerful position to shape policy.

With the government's factional life in somewhat of a stasis, the SNSC is one of the more trustworthy and broad-based decision-making avenues. It was the body which decided on key wartime decisions in the past few months. Previously, it decided not to enforce the draconian new hijab bill passed by the hardliner-dominated parliament.

What next?

First, Larijani might assume a leading role in negotiations with the West, including the nuclear talks. This task has often fallen to the national security advisor, as it did to Larijani himself when he first served in this position from 2005 to 2007.

Second, these are small and cautious changes. Despite his recent positions, Larijani remains a core establishment figure. He is unlikely to expand the government's base significantly or challenge Khamenei in any way. He was widely hated by many dissidents for his role in airing televised confessions from the state TV, which he headed from 1994 to 2004.

Third, the continued sidelining of hardliners is serious, but it has its limits. Many anti-hardliners had hoped Jalili to lose his seat on the SNSC as part of the changes. But Khamenei has retained him, alongside Larijani, as his two representatives on the body.

A conservative MP from Isfahan province has even expressed hope that the two men could work closely. But Jalili’s own reaction to the appointment of Larijani speaks volumes both about his position and how vulnerable it could be.

In a controversial post on X, Jalili compared those who advocate diplomatic ties with the West to the Israelites, in the Quranic story of Moses, who started worshipping a calf. This seems to have been a step too far even for many hardliners. Tasnim—a news agency close to the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC)—urged Jalili to “stay away from radicalism and excitement.”