The American presidency can often be a struggle between the state’s bureaucratic institutions and the president’s individual vision, as the role-holder seeks to leave their mark on political history. More than a clash of viewpoints, this is a struggle between legal rational authority, grounded in precise institutional calculations of cost and benefit, and charismatic authority, which tends to break with established patterns and reshape reality by taking risks.

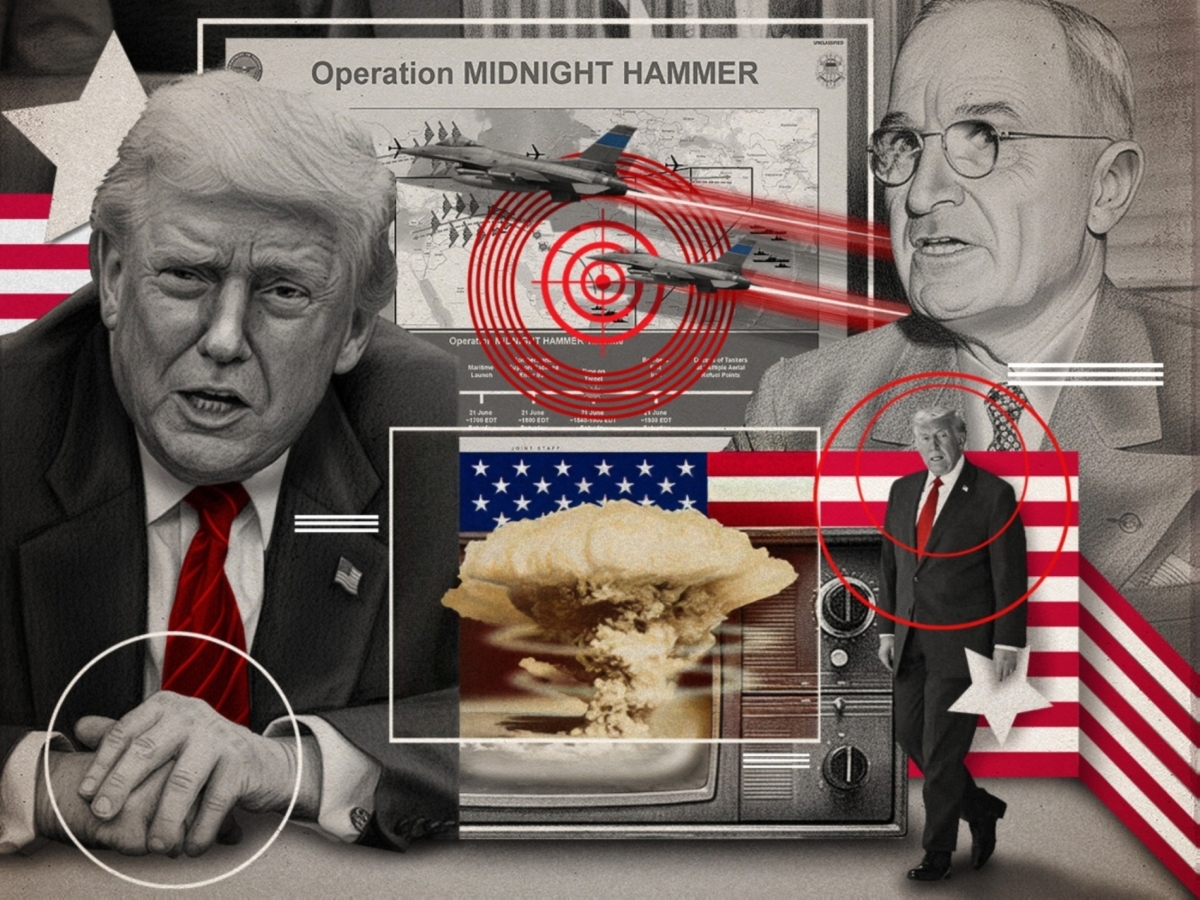

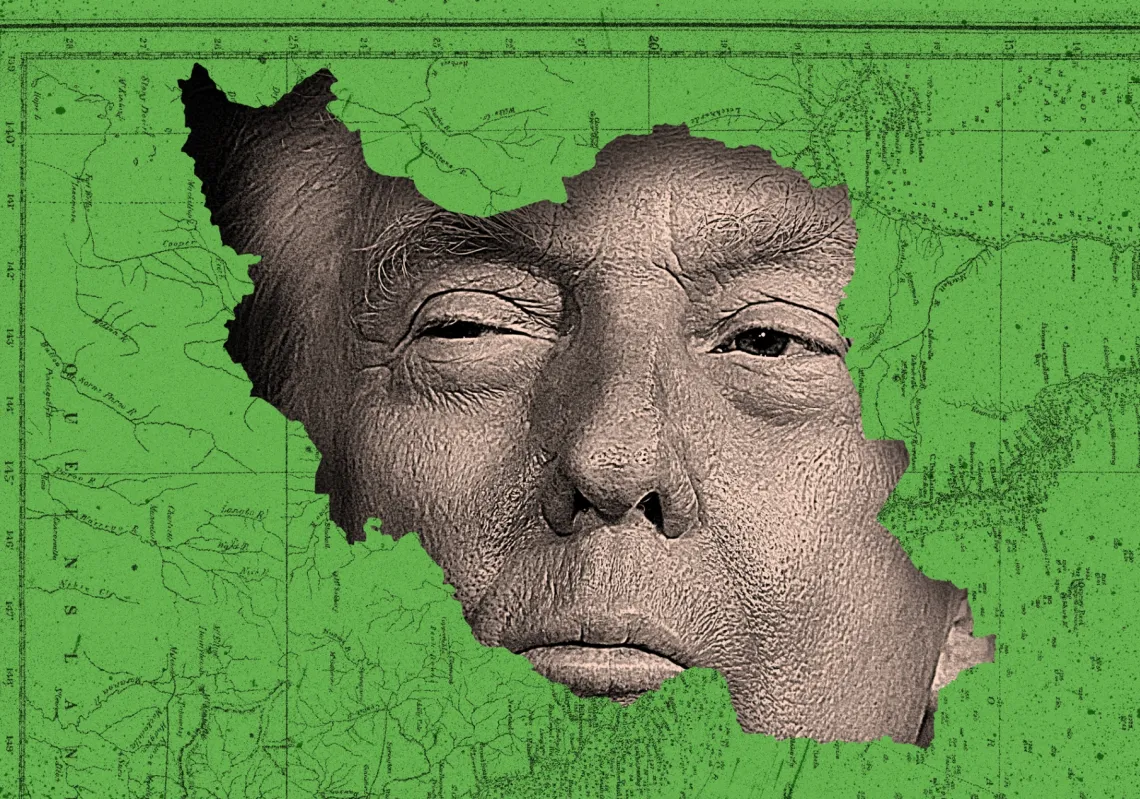

Under the current US President Donald Trump, the balance appears to have tilted decisively towards the latter. Washington’s ingrained strategic caution, which has shaped decades of foreign policy, has given way to Trump’s penchant for pre-emptive, shocking action, quickly redefining the United States’ national interest and its limits.

This change is not solely down to the current White House occupant. Rather, it reflects a structural reversal in how intelligence and operational risks are assessed, and in their tolerance thresholds. Previous administrations were more risk-averse, fearing the consequences of failure on a president’s political future and the standing of the state. Trump’s administration, by contrast, is ready to gamble, using shock as a primary instrument for breaking geopolitical deadlock.

It is important to unpack that doctrinal shift, comparing recent successes to past approaches that typically constrained presidents. It is also crucial to understand how this is reshaping the meaning of national interest and what effects it is having on the global balance of power.

Kennedy and Carter

The history of major 20th-century American intelligence operations is of harsh lessons that would shape the thinking in Washington for decades to come, with losses leaving a deep and indelible mark. In 1961, President John F. Kennedy inherited an intelligence plan drafted by his predecessor, Dwight D. Eisenhower, to invade Cuba. Due to land at the Bay of Pigs, the operation was a humiliating failure.

That failure was not merely a battlefield setback. It dealt a direct blow to the prestige of the American presidency at the height of the Cold War. Intelligence miscalculations showed Kennedy as weak. Two years later, it encouraged the Soviets to test Washington’s limits by placing nuclear weapons on the island. The subsequent standoff, which became known as the Cuban Missile Crisis, brought the world to the brink of nuclear war.

Another dramatic scene played out during Jimmy Carter’s presidency in 1980. Operation Eagle Claw was an attempt to rescue 53 American hostages from the US embassy in Tehran, shortly after the Islamic Revolution in Iran. Eight military helicopters were sent to a desert staging area near Tabas, but only five made it. One had hydraulic problems, one had a cracked rotor blade, and another got caught in a sandstorm, so the mission was aborted, but as the US forces prepared to withdraw, one of the remaining helicopters crashed into a transport aircraft that contained both soldiers and jet fuel, sparking a huge fire. Both aircraft were destroyed, and eight servicemen were killed.

Images of the wreckage strewn across the desert were beamed out worldwide. The operation’s failure was due, in part, to the military and bureaucratic establishment’s inability to adapt to changing conditions on the ground. Images of the twisted fire damage became emblems of a failure in leadership. Carter was new seen as a weak president unable to protect American citizens. It led to a crushing election defeat for Ronald Reagan.

These historical incidents produced what might be called an intelligence failure complex, pushing later presidents to favour convoluted diplomatic solutions over bold field operations. With that in mind, Trump’s decision last month to authorise a daring mission to abduct Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro from a military compound in Caracas broke the mould.