In recent days, Kurdish fighters who spent years building vast tunnel networks in the border area between Syria, Iraq, and Türkiye have begun to emerge from their bunkers and leave Syrian territory, as part of a deal struck with the new leaders in Damascus. Many of those leaving quietly and without fanfare belong to the proscribed Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK). Their departure had been sought for more than a year.

It was the most sensitive clause in an agreement signed last month between the Syrian government in Damascus and the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) in Syria’s north-eastern corner. The two sides fought deadly battles in January, beginning in Aleppo, but the SDF were quickly pushed back and forced to agree to terms that they had spent 2025 refusing. The removal from Syrian territory of leaders and fighters from the PKK was a condition set by both Damascus and Turkish authorities, who consider armed Kurdish fighters on their southern border a national security threat.

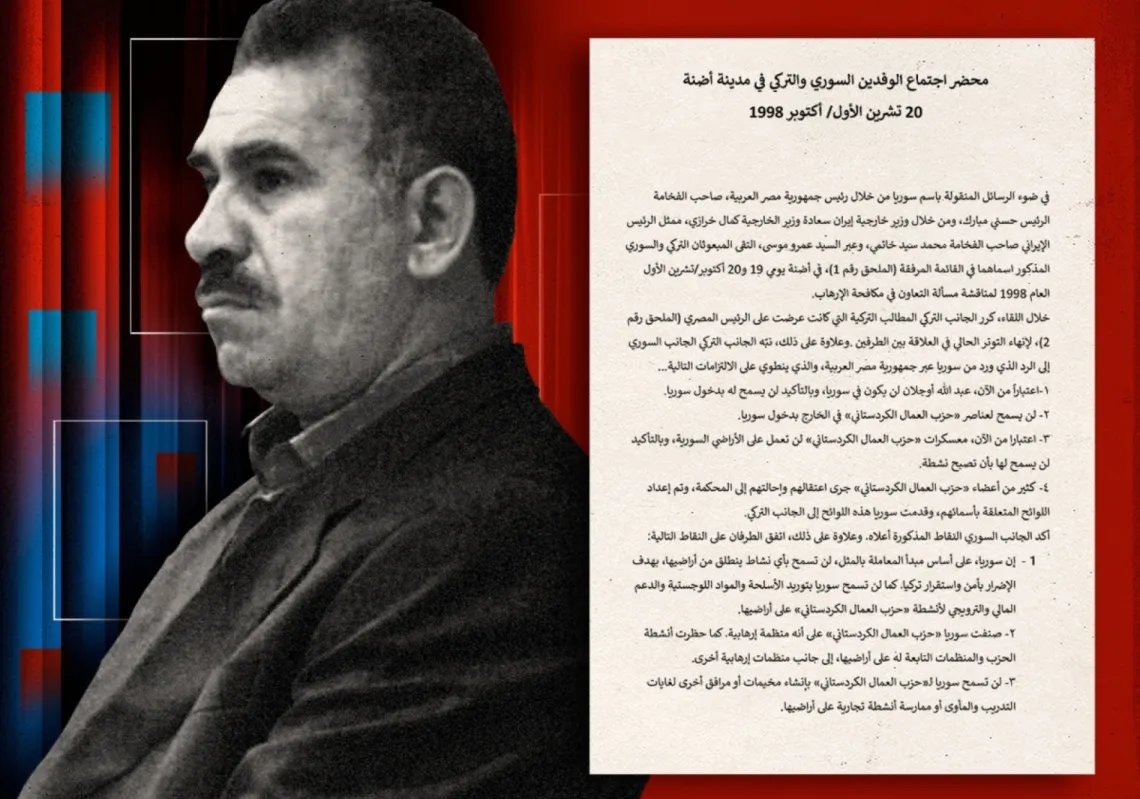

Among those to leave Syria has been Dr Bahoz Erdal, the nom de guerre of senior Syrian-born PKK leader Fehman Hûseyn, best known for ordering attacks against Turkish military outposts from 2007-16. Born in Al Malikiyah in 1969, he studied veterinary medicine at Damascus University (hence his combat name). He became a prominent leader of the PKK’s military wing and helped establish the Kurdish People’s Protection Units, which later formed the core component of the SDF. After PKK leader Abdullah Ocalan was captured by Turkish agents in 1999, Erdal was one of three PKK commanders who took control of the group.

A long time coming

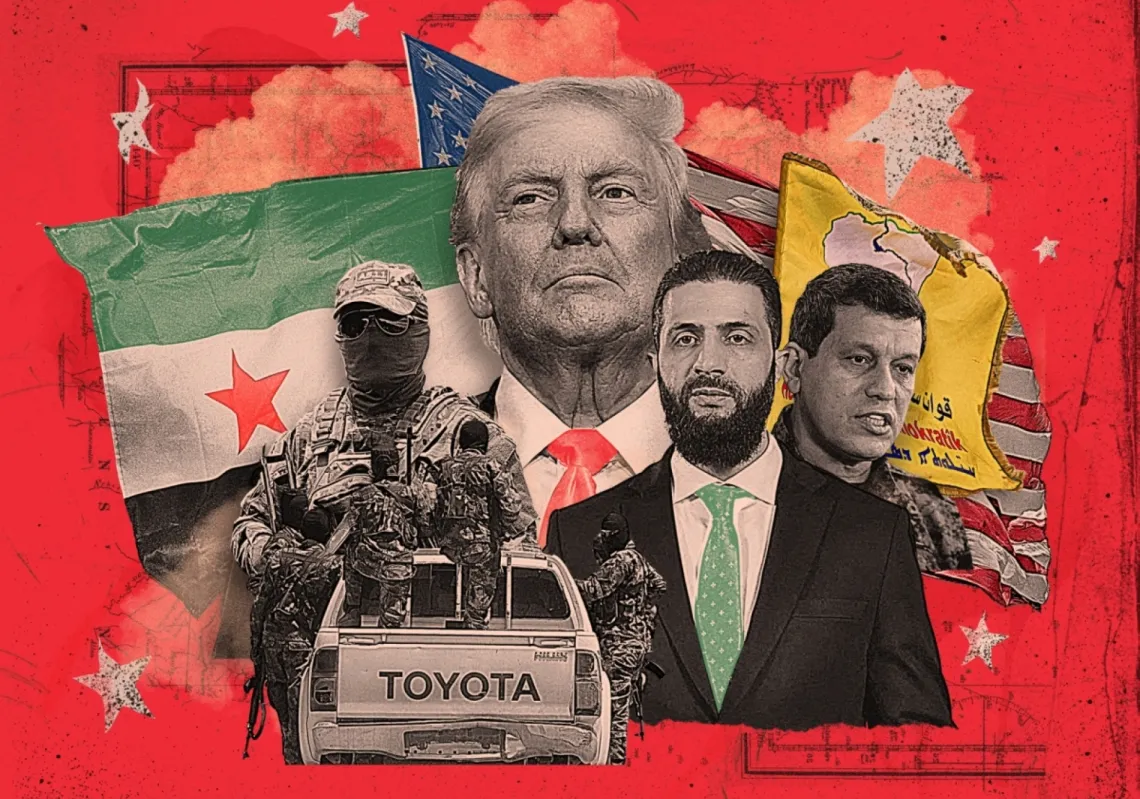

After the fall of Syrian president Bashar al-Assad on 8 December 2024, negotiations took place between Syria’s acting president, Ahmed al-Sharaa and SDF commander Mazloum Abdi. The stipulation that PKK leaders leave Syria came from Türkiye, which had supported al-Sharaa. Ankara has been busy negotiating the PKK’s permanent disarmament with the group’s imprisoned leader, Abdullah Ocalan, in parallel with the negotiations between Damascus and the SDF.

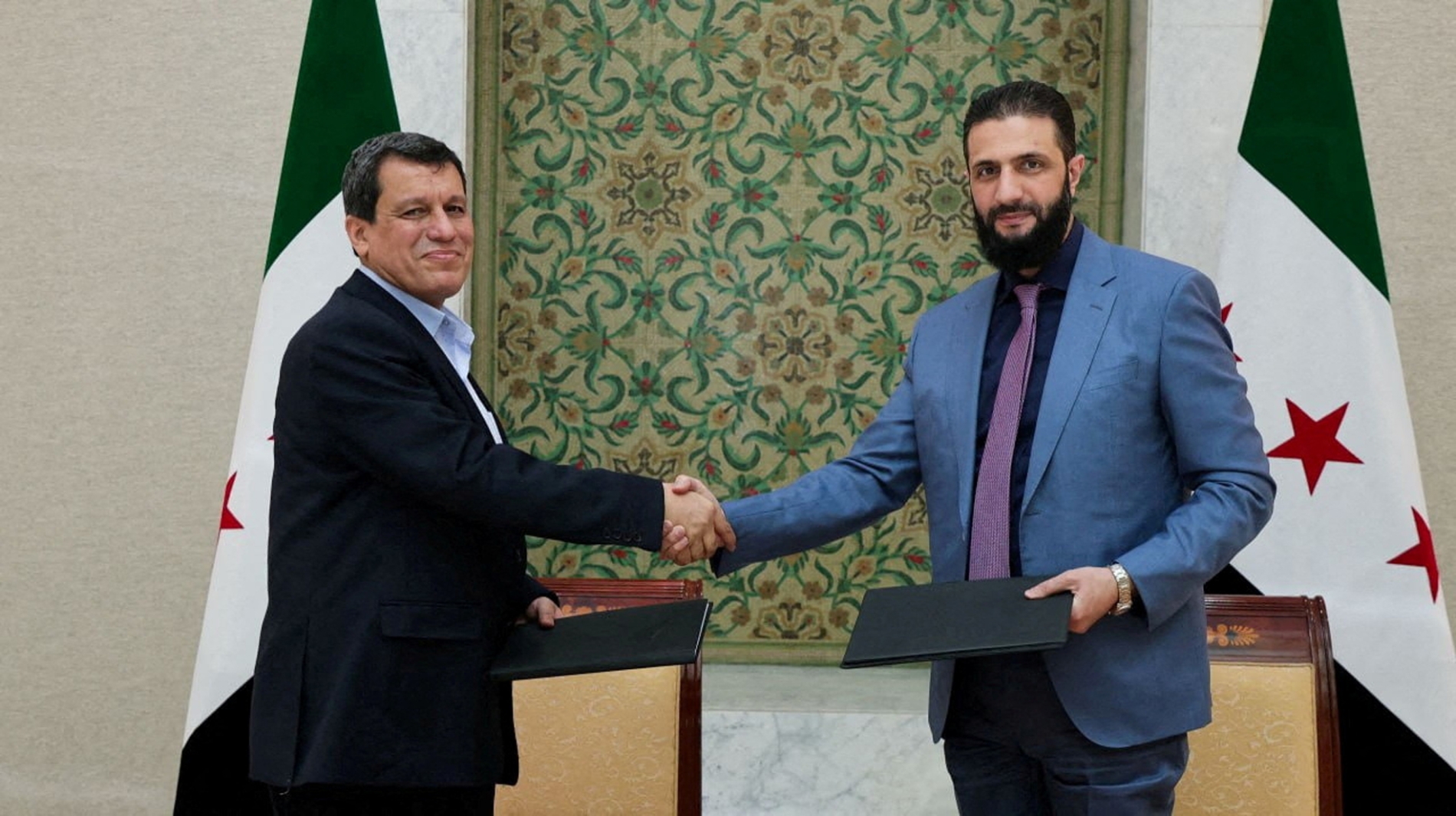

Al-Sharaa and Abdi reached an agreement on 10 March 2025, and although this did not mention the PKK. Last month, sometimes amid fighting between their forces, they agreed on three different sets of terms, in documents dated 4 January, 18 January, and 30 January. The document they signed on 18 January did mention the PKK explicitly.

Mediation between the SDF and Damascus was led by Masoud Barzani, president of the Kurdistan Region of Iraq from 2005 to 2017. Those meetings involved al-Sharaa, Abdi, the US envoy Tom Barrack, and Turkish leaders. It is widely believed that Barzani was crucial in convincing Abdi that PKK leaders had to leave Syria and that the SDF had to cut ties to the PKK.

It was not just the PKK that was no longer welcome. It also covered two affiliated formations: the Hard Power faction and the Revolutionary Youth. Their numbers were estimated in the thousands, including about 1,000 non-Syrians.

The al-Sharaa-Abdi agreement announced on 30 January includes a team from the authority sent to oversee land border arrivals at the Semalka and Nusaybin crossings, to prevent weapons and foreigners from entering.

Enacting the deal

This week, Damascus and the SDF began implementing the agreement. Kurdish politician Nour al-Din Issa has been appointed governor of Al Hasakah. SDF commander Jia Kobani, who has represented the group in negotiations, was named deputy defence minister. Kobani’s nomination was approved by Damascus, but the central government appointed a security director for Al Hasakah, where the SDF has operated with autonomy for several years.

The central government also took control of the Rumaylan and Al Suwaydiyah oil fields and Qamishli airport, and deployed personnel to oversee the launch of Asayish (Kurdish domestic security agency) operations in Al Hasakah and Qamishli. The two cities will be placed under joint administration as state institutions resume work gradually. Consultations are continuing over a deputy interior minister, nominated by the SDF and approved by Damascus, as part of steps to integrate the Asayish into the federal security apparatus.

Some PKK leaders hinted at joining the SDF in the fight against Syrian government forces, using tunnel networks in Al Jazirah, but this raised fears of a more widespread Arab-Kurdish sectarian conflict. For several days, this seemed likely. On 16 January 2026, the Syrian army said Erdal had arrived from the Qandil Mountains (a well-known base for Kurdish fighters in Iraq) to oversee SDF military operations in Aleppo. President al-Sharaa later referred to his role in fighting in Aleppo’s Sheikh Maqsoud, Al Ashrafiyah, and Bani Zaid districts.