America's overarching goal in the region is to ensure a secure Israel and US-friendly neighbouring states with which it can establish commercial ties. But inconsistent policies and mistakes have made this harder to realise. Below is an analysis of the impact of consecutive presidencies on US Middle East policy, beginning with Bill Clinton.

Bill Clinton's tenure

In 2000, Bill Clinton’s second term was ending, and he was in a rush to reach a final agreement between Prime Minister Ehud Barak of Israel and Yasser Arafat, President of the Palestinian Authority. Clinton’s team, like earlier administrations, perceived that a two-state solution would next enable a comprehensive agreement between Israel and the Arab states to establish lasting regional stability.

At the Camp David meetings, Clinton personally delved into the details of maps and borders, examining particular neighbourhoods and streets in Jerusalem, seeking to build a final compromise between Barak and Arafat. Clinton later blamed Arafat for the failure, but a new book by Clinton aide Robert Malley disputes the former president's claim.

While pursuing a two-state solution, Clinton also pressured Saddam Hussein to cooperate with United Nations investigations over Iraq's weapons of mass destruction programme. And while he did order a few missile strikes, he avoided any ground intervention in the region. Like his predecessor, President George H.W. Bush, Clinton did not want to get involved in the messy business of regime change and preferred air power and harsh sanctions to extract Iraqi cooperation. At the time, Secretary of State Madeline Albright infamously justified the sanctions on Iraq despite their terrible impact on Iraqi civilians, including children.

At the same time, Clinton and Albright maintained long-standing American hostility towards Iran. Their hostility resulted from worries about Iranian support for Hezbollah and Palestinians, as well as indications of Iranian interest in weapons of mass destruction. Clinton, therefore, blocked a $1bn deal between Iran and the American oil company Conoco in 1995, which then-Iranian President Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani had hoped would improve bilateral relations. Instead, the Clinton administration tightened sanctions on Iran as part of a “dual containment” policy against Iraq and Iran together.

Clinton wasn't interested in boosting political reform in the region. When I worked at the US Embassy in Algiers from 1994 to 1997, amidst the horrible civil war where Islamist terrorists and government security forces committed atrocities, no senior administration official in Washington raised government violations with Algerian officials. The same was true with repressive governments such as Saddam’s Iraq.

Later, I was part of the American team directing the special bilateral initiative between Clinton’s Vice President Al Gore and Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak, but the American focus was on economic liberalisation in Egypt rather than on human rights. The US perception was that a comprehensive peace in the region, together with economic growth—not respect for civil and human rights—would bring stability.

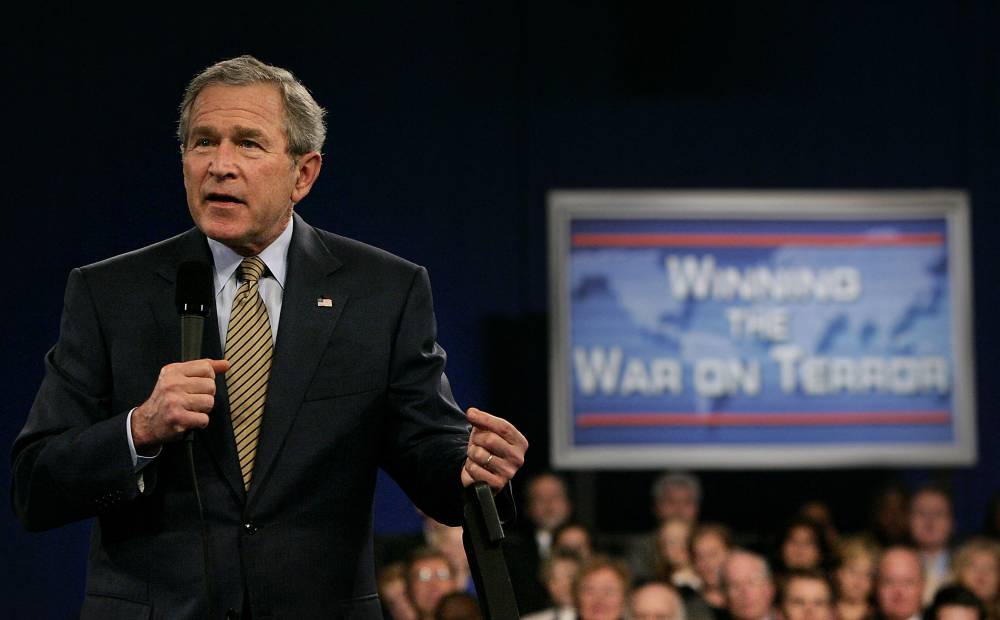

George W. Bush's tenure

After the 9/11 attacks that killed nearly 3,000 people on September 11, 2001, George W Bush launched his infamous War on Terror, beginning with the US invasion of Afghanistan and then later Iraq. Work towards a two-state solution was halted indefinitely during this period as American priorities were elsewhere.

Notably, the White House had no good evidence of Saddam’s involvement with al-Qaeda but justified the invasion on the grounds that Saddam one day might cooperate with the terror group. It is worth noting that two senior American diplomats specialising in the Middle East, William Burns and Ryan Crocker, convinced Bush’s Secretary of State Colin Powell of the risks of invading Iraq, but Powell could not persuade Bush. However, the quick victory Bush had expected in both Iraq and Afghanistan never came. US military hegemony and the support of international forces weren't enough.

The George W Bush administration believed the source of terrorism in the region stemmed from the Arab street's frustration with repressive, corrupt governments across the region. In a major departure from the Clinton administration, Bush ramped up political pressure on many governments, including longtime allies. Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice cancelled a visit to Egypt in 2005 because Mubarak rejected a human rights conference in Cairo and arrested political opposition figure Ayman Nour.

In 2002, the White House established the Middle East Partnership Initiative within the State Department's Middle East and North Africa Directorate, which was managed by a Republican Party loyalist, to promote human rights in the region. When I returned to Algeria as ambassador in 2006, Washington was ready to raise human rights and civil liberties issues with the Algerian authorities. In addition, the Partnership Initiative enabled us to train Algerian civil society elements, such as independent newspapers, in business and organisation management.

When I returned to the US Embassy in Baghdad in 2008, our budget for promoting human rights and civil society in Iraq was a whopping $70mn a year—more money than we could spend, so some went to groups that weren't even serious.

Barack Obama's tenure

President Barack Obama came to office determined to end US involvement in wars in the Middle East. He adopted the view that the region was merely a collection of tribes engaged in conflict, and it wasn't America's job to resolve it. Unlike the previous Democratic Party president, Bill Clinton, Obama wasn't interested in trying to resolve the Israel-Palestinian conflict and gave no support to Secretary of State John Kerry’s efforts to launch an initiative in 2013.

By contrast, Obama and his first Secretary of State, Hillary Clinton, saw a connection between poor governance in the region and instability. Clinton, on 12 January 2011, delivered a sharp critique in Doha of Arab governments’ corruption and repression. Her speech came the day after President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali fled Tunisia and a month before the Egyptian army ousted Hosni Mubarak from power amidst anti-government protests in Egypt.

Early in the so-called Arab Spring, Obama voiced public support for the demonstrations despite having no intention to intervene militarily. Years later, Obama and I argued in the Oval Office about whether a US president should publicly demand that a leader step down if the US had no intention of getting involved. I warned that, should the leader refuse to leave, the US would appear weak, and that he was also giving false hopes to the local opposition. He argued that the US president should publicly demand respect for human rights without any obligation to intervene.

In January 2011, Obama had urged Mubarak to depart, but it was the Egyptian street and the Egyptian army that ultimately removed him—not Washington. When the Arab Spring spread to Libya, Obama discreetly lent logistics and intelligence to support the March 2011 multinational intervention against Muammar Gaddafi. An Obama official commented that the Americans were leading European and Gulf allies there “from behind.”