The fall of the Sudanese city of el-Fasher to the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF) on 26 October was a strategic turning point in the country’s brutal civil war that has been raging since April 2023, carrying devastating consequences.

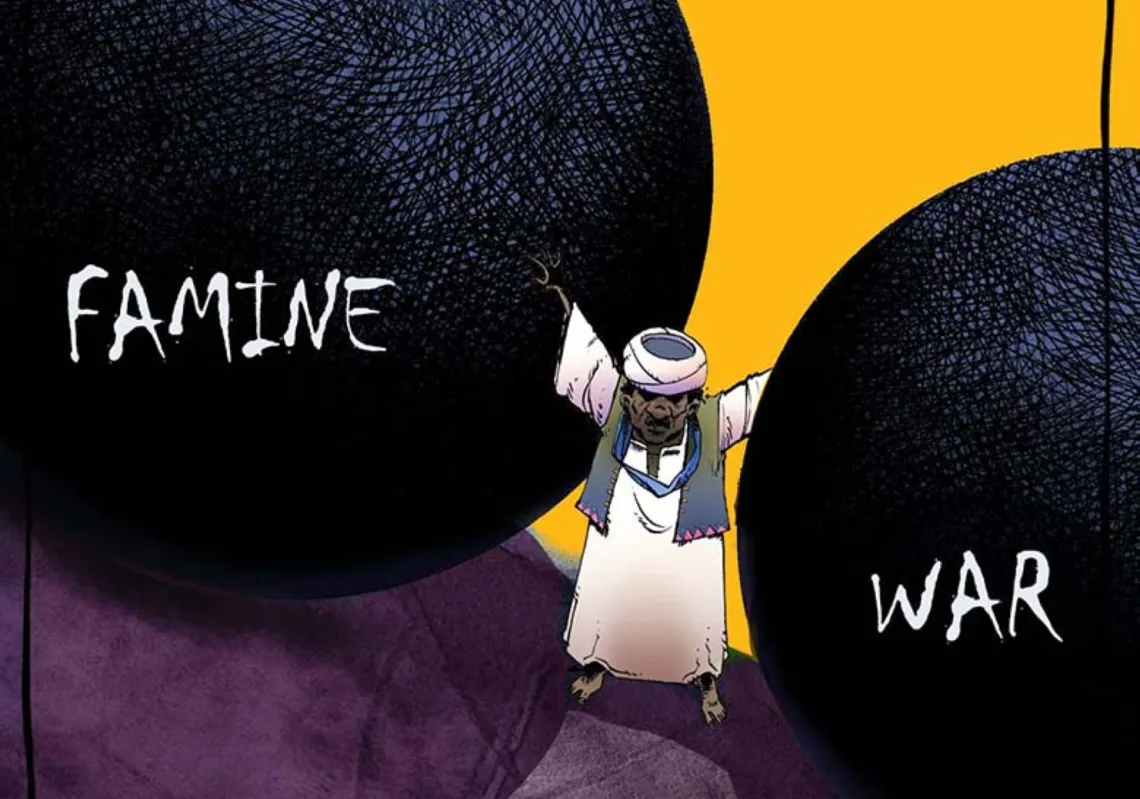

Since the outbreak of war between the Sudanese government and the RSF, el-Fasher—the capital of North Darfur—has been a primary RSF target. It was fully encircled in May 2024 and has been under siege ever since, its people slowly starving, with the government’s aerial and ground supplies choked off.

For 500 days, the Sudanese army, local tribal groups, and dedicated civilian volunteers defended the government’s final stronghold in the Darfur region—an area the size of Spain, located in western Sudan. Holding out for 500 days made el-Fasher a stark symbol of the suffering wrought by Sudan’s war.

An administrative centre and major commercial hub, the city also carries historical weight, having been the former capital of the Sultanate of Darfur. Latterly, it was a forward military base for government forces. In 2009, the United Nations estimated its population at around 500,000. Before the outbreak of war in 2023, its population had swollen to an estimated 1.5 million, many having fled there from the RSF.

Control of el-Fasher gives the RSF full access to critical supply routes. To the north are the neighbouring states of Chad and Libya, through which provisions, ammunition, and fighters are moved, while to the south is the RSF-controlled city of Nyala.

Families hid in trenches, bodies lay in the streets and children were killed in front of their parents as Sudanese paramilitaries advanced into the western city of El-Fasher, survivors told AFPhttps://t.co/MIWF96d3V7 pic.twitter.com/M3pq5LUsYm

— AFP News Agency (@AFP) October 30, 2025

From siege to slaughter

Analysts have long thought full RSF control of Darfur was a matter of ‘when, not if,’ and since May 2024, there have been escalating attacks on the city’s outskirts, targeting residential areas and vital infrastructure, accompanied by a complete blockade of all major access routes. Intensifying artillery bombardments and drone strikes prompted a mass exodus from surrounding neighbourhoods and nearby villages.

By the end of 2024, the city’s population had fallen below 800,000. By the time the RSF finally took control, that figure had dwindled to around 300,000. According to estimates from UN agencies and the Red Crescent, this sharp fall was driven by widespread displacement and mounting deaths due to violence and starvation.

As el-Fasher’s social fabric began to break down, hundreds of thousands fled, leaving the city all but deserted. Yet even in flight, the RSF pursued them, executing many on ethnic grounds. Those who remained were trapped between violence and despair, as the RSF cut off food and medicine while targeting fleeing civilians. Humanitarian aid was blocked, leading to the collapse of relief networks and outbreaks of disease.

And upon taking over el-Fasher, horrific attrocities have already been committed with the United Nations confirming RSF militants massacring 460 patients and their companions at the Saudi Maternity Hospital there.

Civilians fled to Tawila some 60 kilometres away with many arriving “dehydrated, injured and traumatised,” according to a post on social media by the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs.

Since July 2024, Sudan has recorded more than 96,000 suspected cases of cholera, resulting in 2,400 deaths, with the open-air prison of el-Fasher being the epicentre. With a lack of clean water and medical facilities targeted by RSF bombing, infectious diseases spread rapidly, particularly among the city’s 130,000 children, who accounted for around half of the besieged population by October 2025.

With hospitals and clinics targeted, it appears that nowhere has been off limits. Even places of worship have not been spared. On 19 September, the RSF launched a drone strike on Al-Daraja Mosque in el-Fasher, killing at least 78 worshippers during dawn prayers and injuring many more. On 9 October, another mosque in the city was bombed, killing 13 worshippers and injuring 20.

Foreign-sponsored mercenary fighters from Colombia were first reported in Sudan in 2024, fighting for the RSF. This introduced a new and perilous dimension to the siege of el-Fasher. In August, Sudan’s air force said it had destroyed an aircraft carrying Colombian mercenaries to Nyala, killing at least 40 people.

The Colombians have primarily been tasked with conducting advanced sniper operations, training militia units in the use of sophisticated drones, and executing complex special operations against fortified government positions. Their involvement has led to increased casualties among the city’s defenders, hastening the collapse of defensive lines and compounding civilian suffering.