Syria and Türkiye are currently in discussions to expand the scope of a key diplomatic deal which brought them back from the brink of military confrontation.

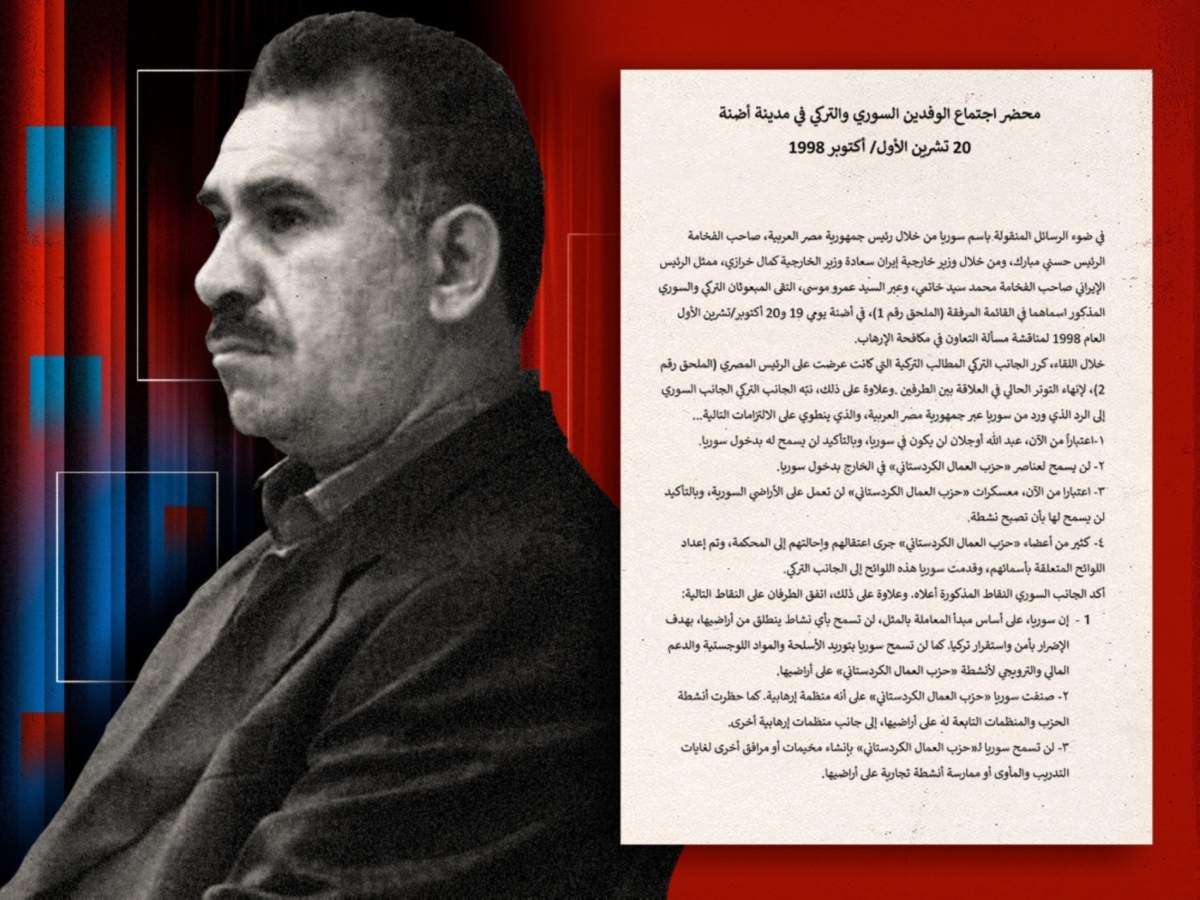

The Adana Agreement was struck in 1998. It led to the expulsion of Abdullah Öcalan, leader of the Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK), from Syria, defusing the cross-border crisis.

Now, it is once again being used by Ankara and Damascus as a mechanism to manage arrangements between the countries regarding the territory around their frontier.

According to confidential sources and a report by the news agency Bloomberg, negotiations are underway to supply the Syrian side with military equipment – from armoured vehicles to drones and air defence systems – in exchange for extending Turkish military incursion rights in northern Syria from five kilometres to 30 km.

This would enable Turkish forces to pursue PKK elements across a zone mirroring the “safe area” established under the terms of an agreement between Türkiye and the United States in late 2019, between Ras al-Ayn and Tal Abyad.

Ankara has exercised caution in deploying military equipment deep into Syrian territory. Previous attempts to establish bases in central Syria provoked Israeli air strikes.

Now, the renewed focus on an expanded Adana Agreement comes at a critical juncture for the two nations that struck the original deal, as well as for the wider Middle East, at a time of turmoil for the region and a shifting geopolitical world order.

Negotiations are ongoing between the transitional national government in Damascus and the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), which includes the Kurdish YPG militia, viewed by Ankara as an extension of the PKK, regarding their integration into the Syrian army.

Meanwhile, the government of Türkiye's President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has reached an understanding with Öcalan—who has been in Turkish custody since early 1999—on abandoning armed Kurdish separatism in favour of a peaceful political approach.

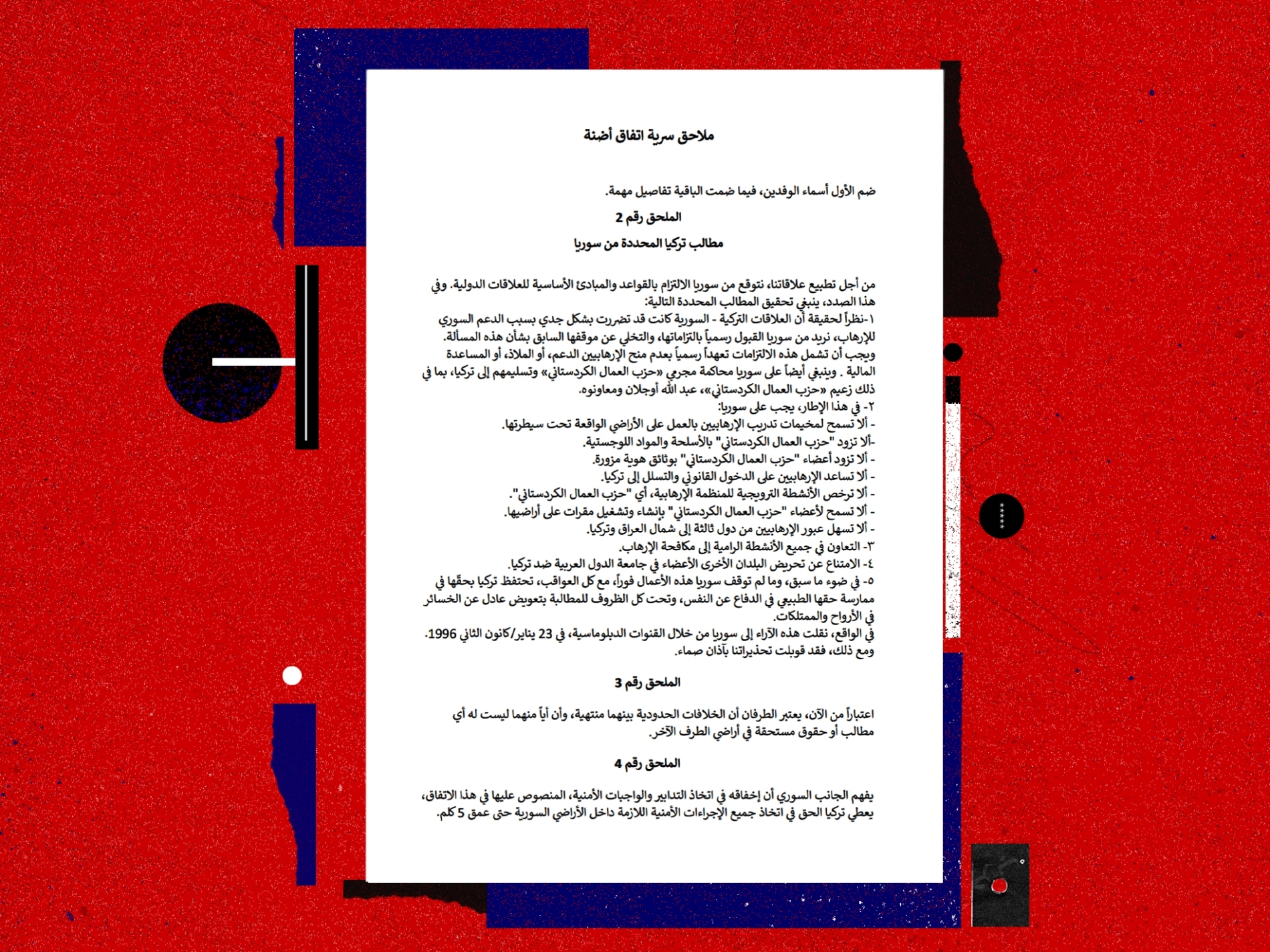

As the Adana Agreement moves back into the spotlight, Al Majalla examines the key questions surrounding the deal: What are its public and confidential clauses? What does its revival and potential expansion entail? And what is the story of Abdullah Öcalan and his ties to Syria?

Fluctuating relations

Relations between Syria and Türkiye have fluctuated dramatically over the decades. They were on the brink in the mid- and late 1990s. Ankara leveraged its control over water resources in the Euphrates and Tigris rivers to apply pressure on Damascus. In response, Syria hosted the PKK leadership and its founder, Abdullah Öcalan, from the early 1980s.

Öcalan maintained links with Syrian intelligence, and his fighters collaborated with Palestinian factions during Syria’s military presence in Lebanon. He remained politically isolated until 1992, when he met Syria’s Vice President Abdel Halim Khaddam for the first time.

Subsequent meetings aimed to persuade Öcalan to seek a political resolution with Türkiye as part of Damascus’s mediation efforts with Prime Minister Necmettin Erbakan’s government.

These attempts failed, and Syria continued to harbour Öcalan, rejecting Turkish demands for his extradition or expulsion. By 1998, Türkiye had mobilised troops along the Syrian border and issued a clear ultimatum: Öcalan must leave.

Previously, Al Majalla published official Syrian documents that Khaddam had transferred to Paris prior to his defection in 2005. In light of renewed interest in the Adana Agreement, further Syrian documents are now being released, revealing the story they tell.

The story behind Abdullah Öcalan’s high-profile exit from Syria

In mid-1998, following Turkish threats of military action unless Öcalan was expelled, Syria’s President Hafez al-Assad met Khaddam in Latakia on 1 October. Khaddam recounted:

“While we were discussing Lebanon, the aide entered and handed him an envelope. We read its contents—it contained a statement by Turkish President Süleyman Demirel threatening Syria with military action if Öcalan was not handed over, accusing Syria of supporting Kurdish terrorism that had claimed tens of thousands of Turkish lives.”

After deliberation, al-Assad and Khaddam concluded that the threats were “coordinated with Israel and the United States, linked to pressure on Syria to reach a settlement with Israel (given secret negotiations between al-Assad and Israel’s Benjamin Netanyahu), and part of a new regional alliance,” according to Khaddam.

Egypt’s President Hosni Mubarak then contacted al-Assad, and they agreed on a visit to Damascus on 4 October 1998. Following discussions, Mubarak travelled to Türkiye, met with Demirel, and returned to Damascus on 6 October for a closed-door meeting with al-Assad.

The day before, Foreign Minister Farouk al-Sharaa contacted Khaddam and requested a private meeting to discuss the Turkish threats. Khaddam recalled:

“I received him at 8 p.m. We discussed the potential escalation with Türkiye and the issue of Öcalan’s presence in Syria and the need for his departure.”

Khaddam had previously met Öcalan in July 1996 and agreed on his departure from Syrian territory, but Öcalan “evaded implementation” of it, Khaddam stated:

“Such a decision was unavoidable—national security cannot be compromised for the sake of an individual or a party.”

Khaddam and al-Sharaa summoned General Adnan Badr al-Hassan, then head of Political Security, to discuss how to inform Öcalan. Assad preferred Khaddam to deliver the message personally, given their prior acquaintance. It was agreed that the meeting would take place discreetly at al-Hassan’s office on 6 October.

The meeting went ahead as planned. Öcalan was surprised to see Khaddam. After lengthy discussions, the Syrian vice president conveyed the decision. The exchange was as follows:

Öcalan: “I will contact our friends in Greece to arrange the matter” (his departure).

Khaddam: “Time is not on our side. The situation now is different from a year ago when we discussed this.”

Öcalan: “I will make arrangements swiftly.”

Öcalan left Syria for Greece on 8 October. Greece nearly arrested him, but his associates arranged for his transfer to Russia, where he remained for roughly two weeks.

Under US pressure, despite a resolution in the Russian parliament granting him political asylum, Moscow declined to host him. Öcalan then sought refuge in Italy, where he stayed briefly.

Following further pressure from the US and Türkiye, and coordination with Greece, he was moved to Kenya. There, in Nairobi, Turkish intelligence abducted him in February 1999. He was tried and sentenced to death months later, though the sentence was commuted. He remains imprisoned to this day.

Tense negotiations

Back in 1998, there was a direct telephone call between Egypt’s President Hosni Mubarak and Türkiye’s President Süleyman Demirel—during which Mubarak relayed Syria’s position. Both presidents agreed to dispatch Egypt’s Foreign Minister Amr Moussa to Ankara on Monday, 11 October.

This initiated a flurry of Egyptian–Syrian–Turkish communications. On 12 October, Moussa visited Ankara and met with President Demirel and Foreign Minister İsmail Cem, presenting Syria’s response. The atmosphere was reportedly positive, and the parties agreed to hold a security meeting on the Syrian–Turkish border within days.

On 13 October, the Turkish ambassador informed Saba Nasser, director of the Europe department at the Syrian Foreign Ministry, that both governments had agreed to convene a bilateral and confidential meeting in Ankara, Adana, or Diyarbakır on 16 October.

Nasser proposed Aleppo or Latakia as alternative venues, but the ambassador declined, stating that the Syrian delegation would be hosted at official premises to avoid hotels and other locations frequented by journalists. The Turkish delegation would be led by Ambassador Uğur Ziyal, Deputy Secretary-General of the Foreign Ministry, and include military and intelligence officers.

Türkiye requested that each delegation bring its own Turkish-language interpreter and instructed its team to adhere strictly to Mubarak’s initiative. The Turkish ambassador stated unequivocally:

“Security will be the sole topic of discussion. Any attempt to broaden the agenda will not be entertained.”

Nasser cautioned:

“Time is extremely short. We must not squander this momentum or miss this opportunity.”