Diplomatic activity within and about Syria is currently running at a frenzied pace, as parties both internal and external jostle for position, ahead of what some suspect may be pending clashes between the Syrian government and Syria’s Kurds, well-armed and trained mostly by the US throughout the years.

There had been hopes of calm after the violence on the coast in March and the south, around Sweida, in July, but a recent conference held by the Kurdish-led SDF, which senior Druze and Alawite leaders also attended virtually, has rattled Ankara.

Druze leader Hikmet al-Hijri and Sheikh Ghazal Ghazal, a spiritual leader of the Alawite minority, both agreed at the ‘Joint Position Conference’ held in al-Hasaka on 8 August that Syria should now be governed through a decentralised system, with autonomous areas allowing their armed groups to remain armed.

Recent developments suggest that Syria’s new government may not in fact be able to convince its disparate factions to unite, as many had hoped. For Türkiye, Syria’s neighbour to the north, armed autonomous Kurdish groups on its border are a red line and cannot be allowed. Meanwhile, Israel, Syria’s neighbour to the south, opposes a strong centralised government in Damascus that could supplant the autonomy of the Druze and other minorities.

Cue the diplomacy

There is intense traffic both in the military sphere and in the diplomatic arena. In reaction to the outcome of the meeting in al-Hasaka, the Syrian government said it would not participate in any meeting with the Kurds anywhere other than Damascus (Paris had been suggested by the SDF).

In parallel, the Syrian army has been deployed to some areas in the oil-rich north-east of the country that the SDF controls. The SDF’s armed wing is the YPG, which Türkiye considers to be linked to the terrorist group, the PKK. Clashes have already been reported along the Euphrates and in Deir el-Zor.

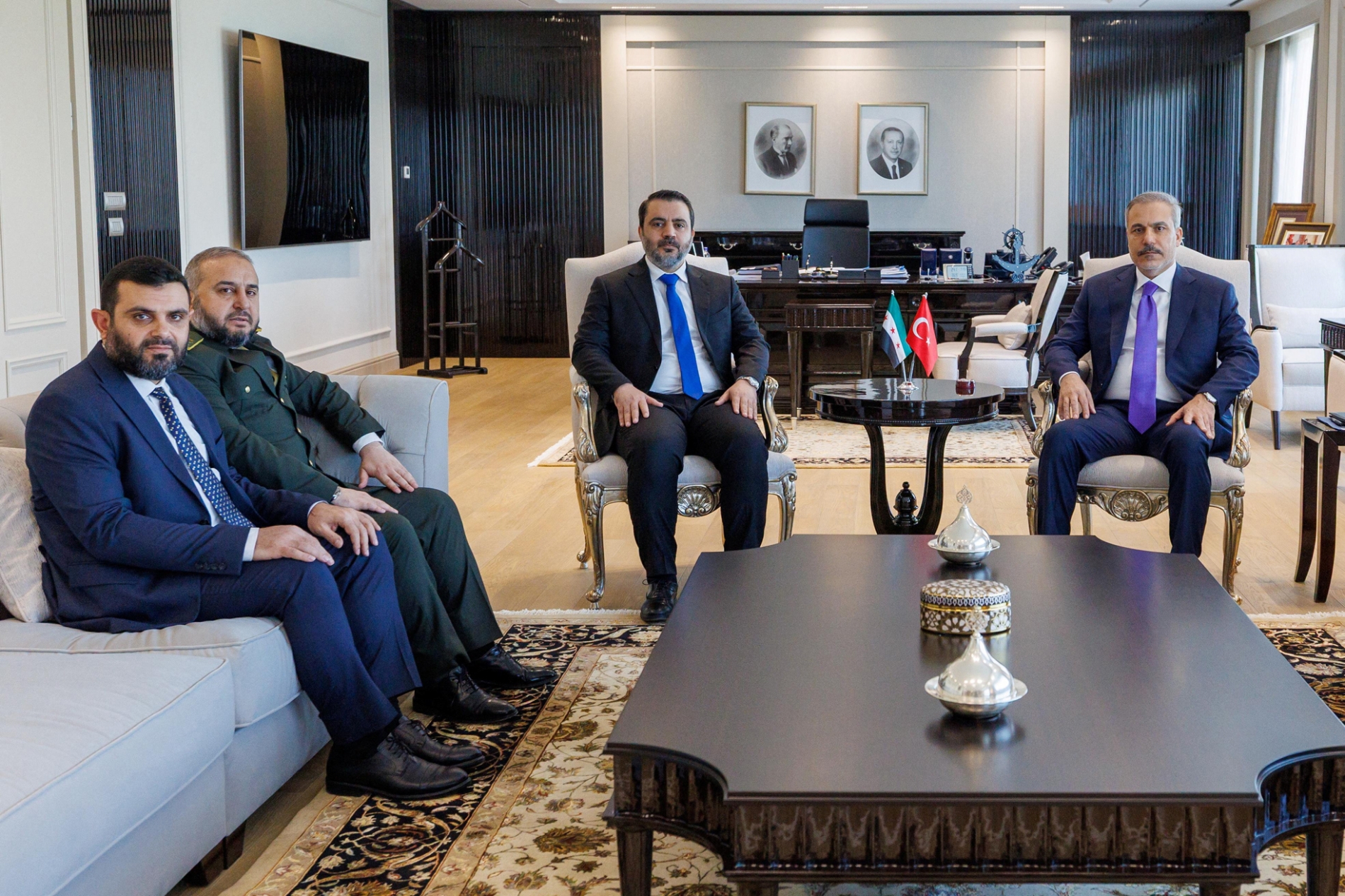

On 7 August, Turkish Foreign Minister Hakan Fidan visited Damascus to meet Syrian Foreign Minister Asaad al-Shaibani and President Ahmed al-Sharaa. A week later, there was a return visit comprising al-Shaibani, Syria’s Defence Minister Maj. Gen. Murhaf Abu Qasra, and Syria’s Director of the General Intelligence Service, Hussein al-Salama

In Ankara, the parties signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) on “joint training and consulting” of their armed forces. Türkiye is offering to develop and modernise the Syrian army’s capabilities. This includes exchanges of military personnel and specialised training in counter-terrorism, mine clearance, logistics, and peacekeeping. At the press conference, Fidan did not pull his punches.

He stated that the SDF had not fulfilled the commitments it undertook when signing an agreement with al-Sharaa and the Syrian government on 10 March 2025. He accused the Kurdish-led group of stalling and Israel of stirring up trouble in Syria. He said Türkiye would not be deceived, hinting at armed options if the situation did not change. Likewise, al-Shaibani said Israeli attacks on Syria were directed at Syrian sovereignty, adding that Tel Aviv sought to provoke sectarian conflict within Syria.