The spotlight for US policy in the Middle East will shift from the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) meeting in New York to Washington, DC, where US President Donald Trump will meet with Israel’s Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu on Monday for the fourth time in eight months.

Trump used his UNGA speech to reinforce priority themes central to his worldview, including a harsh tone on migration and scepticism about climate change, but offered little in his speech that would come close to a pragmatic game plan for tackling the world’s toughest problems.

But it was a meeting on the sidelines of UNGA he had with top diplomats and figures from Arab and Muslim countries—and a statement he made about the idea of Israel annexing the West Bank—that will set the tone of Trump’s meeting with Netanyahu. Given Trump’s penchant for unpredictability and discrepancies between words and deeds on the global stage, one cannot put too much stock in any particular meeting or statement he makes.

“I will not allow Israel to annex the West Bank,” Trump said after returning to the White House from New York. “There’s been enough. It’s time to stop now.”

Some observers attached great significance to his statement, suggesting it was a possible indication of where Trump might go in the coming weeks regarding the Middle East. But it is important to keep two things in mind. First, US presidents have had many “red line” moments in the past and have repeatedly failed to live up to the commitments they made.

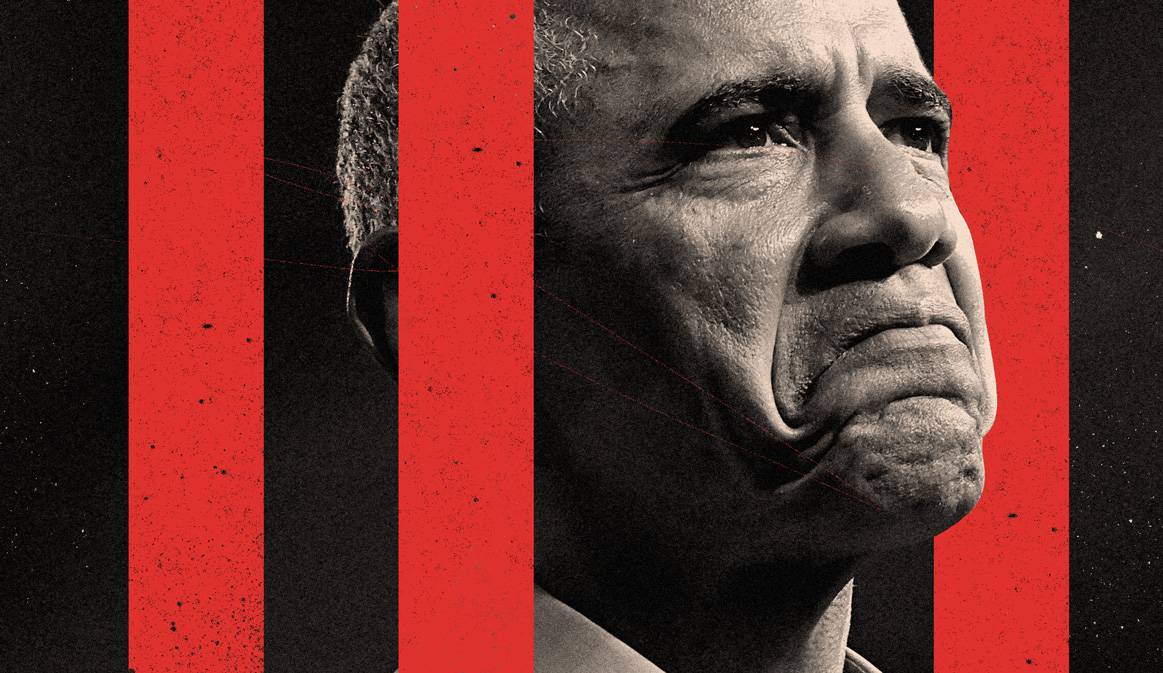

Most famously, US President Barack Obama stated early in Syria’s civil war that the Assad regime’s use of chemical weapons would be a “red line” that would have “enormous consequences” that would change his calculus about whether he would order the US military to intervene more directly in that deadly conflict that devastated the country.

When the Assad regime ended up using chemical weapons several times against its own people, and the Obama administration did not have a clear and effective response, this sent a resounding message across the Middle East about how skittish and uncertain America had become about its own role and purpose in the Middle East.

Read more: Obama’s hesitation in Syria: The red line that never was

Second, Trump himself regularly makes statements on a single issue without backing those statements up with actions or policies. He also often makes sudden shifts in policy statements, like he did this past week on the Ukraine war, asserting that Ukraine could win back all of its territory lost to Russia, which was the opposite of much of what he said in the first few months of his second administration.

Nothing Trump has said and done about Russia’s war against Ukraine in his second term has come close to living up to his campaign assertion last year that he would end the war in one day. Trump’s loose use of words is so unpredictable and unreliable, given all of his shifts, that this statement about annexation may have little value at all—particularly if it’s not backed up by a policy shift.

Actions speak louder than words

But actions speak louder than words. A meeting that Trump had last week with Arab and Muslim leaders to present the contours of a Gaza peace plan may mean a lot more than his statement opposing Israel’s annexation of the West Bank. This meeting was held the same week that France, Saudi Arabia, and other countries organised a session to symbolically recognise a state of Palestine, an effort that the Trump administration has opposed.

If the reported 21-point plan for what the future might look like between Israelis and Palestinians, particularly in post-war Gaza, serves as a basis for engaging key countries in the Middle East—including Trump’s upcoming meeting with Netanyahu—it might produce some renewed hope for an end to the awful war in Gaza and a pathway to a lasting peace deal.

Trump projected optimism on Sunday when he posted the following on his Truth Social platform: “We have a real chance for GREATNESS IN THE MIDDLE EAST.“ALL ARE ON BOARD FOR SOMETHING SPECIAL, FIRST TIME EVER. WE WILL GET IT DONE!!! President DJT.”

But in a seemingly routine pattern, Netanyahu appeared to pour cold water on the idea when he told Fox News that the plan hadn't been finalised yet.