Theodor Herzl, the founder of the Zionist movement, felt that the future Jewish state would have allies, declaring that “nations will be compelled to ally themselves with us”. Although the interpretation has been debated, what is certain is that he understood the value of alliances—not only for the establishment of the State of Israel, but for its ongoing survival.

The Zionist movement—and later, Israel—chose its allies meticulously. Early Zionists initially courted the Ottomans unsuccessfully before shifting their focus to the British, which ultimately led to the 1917 wartime Balfour Declaration. This opened the door for European Jews to migrate to Palestine. In the early years of the Israeli state, the French helped with its nuclear programme and fighter jets, but far more important and enduring than Israel’s alliance with either Britain or France was its relationship with the United States.

Israel has always been nimble and pragmatic in its alliances, depending on what its would-be allies could offer. Likewise, nations working with Israel have, at times, found their association to be more burden than boon (including both the French and British). This has led to a revolving door of friends.

Its alliance with the United States was relatively late to bloom, but quickly deepened after the 1967 war, and grew after the 1973 war, when Washington supplied Israel with much-needed weaponry that reversed the losses that Israel had sustained. It has served both parties well.

Unique relationship

For Washington, Israel was a potent instrument in its Cold War efforts to counter Soviet influence in the region. The potency came, in part, from military superiority using American technology. Ever since 1973, the US has effectively guaranteed Israel’s qualitative military edge over its Arab neighbours, leading to Israeli dependency on the US.

The relationship is unique in world politics, not least for the way in which Israel influences US politics, effectively becoming a domestic matter for the American public. The so-called ‘Israel Lobby’ was explored by two prominent US academics, John Mearsheimer and Steven Walt, in their book The Israeli Lobby and US Foreign Policy.

Having armed Israel, Washington has availed itself of Israeli capabilities to further its regional interests, but the US does not depend exclusively on Israel to secure its strategic goals in the Middle East. During its 2003 invasion of Iraq, for instance, Israel did not lend its ally and benefactor its military support.

The US has taken action to support Israel’s regional interests, beginning with the air bridge in the 1973 war, together with the nuclear alert to deter possible intervention by the Soviet Union, all the way through to Israel’s most recent interventions in Gaza, Lebanon, Yemen, and Iran. Throughout, the US has provided weapons and intelligence. Without this, Israel could not have achieved what it has.

Israel’s Iron Dome air defence system incorporates the US THAAD (Terminal High Altitude Area Defence) missile interceptor, which costs three times as much as Israel’s own Arrow system, costing $3mn. Israel used a quarter of its US inventory to defend itself against Iran’s missile attacks earlier this year. Replenishing this inventory will take time and money.

Changing attitudes

Can the US afford to keep supplying Israel? Many in Washington wonder. Weighing on the debate are notable shifts in public opinion. While the US public has long been supportive of Israel, its genocide in Gaza appears to have had a big effect. Most young Americans are now outright hostile towards Tel Aviv. A University of Maryland poll this month found that more Americans side with the Palestinians (28%) than the Israelis (22%).

For Americans aged 18-34 years, the difference is stark: 37% say they sympathise more with the Palestinians, while 11% sympathise more with the Israelis. Politically, it is even more pronounced, with 67% of Democrats compared to just 14% of Republicans. An increasing number say Israeli actions in Gaza look like genocide, and only a third of Americans think US policy in the Middle East mostly advances US interests. A quarter said it “mostly advances Israeli interests”.

Read more: Universities get tough on students after students get tough on Israel

Recent military action in Gaza and Iran has underscored some key Israeli vulnerabilities that could have long-term consequences for Middle East security. While Israel has long balanced preventative and punitive military actions, it has also chosen to ignore the fundamental truth underlying all of its conflicts: that its occupation of others’ territory, and its ready use of force, has not provided it with the security it seeks. It is also now apparent that Israel cannot realise its quest for regional hegemony alone; it needs the active military and political support of the US.

In the past, Washington could compartmentalise its relations with Israel and the Arabs, maintaining its special relationship with Tel Aviv while working with Arab and Gulf states. This policy reached its fruition with the 2020 Abraham Accords, in which Bahrain and the United Arab Emirates agreed to normalise relations with Israel in return for advanced US weaponry, such as fighter jets.

Growing ambitions

Recent months have exposed Israel’s hegemonic designs not only in the Middle East, but more importantly, to American society. Could this impact future US-Israeli relations? While they are mutually dependent, Israel’s dependency on the US is far greater than Washington’s reliance on Tel Aviv, and in Washington today, the vogue is for reduced US exposure to Middle East wars, instead focusing on the rise of China.

The US retains major strategic interests in the Middle East to safeguard its access to regional energy markets and global maritime traffic, so it will not withdraw entirely, but Washington will nevertheless be horizon-scanning, as it seeks a regional security architecture in which the US (not Russia or China) is still the ultimate security guarantor. Ideally, this would include all regional actors, including Arabs, Turks, Iranians, and Israelis, and would include political, military, economic, and cultural dimensions.

Yet Israel's vision for the Middle East (Israeli hegemony) is diametrically opposed to the vision of others, which poses a problem for Washington, if it comes down to a choice between US support for Israel or its support for others. Today, US support for Israel (over that of others) is no longer automatic, even among American right-wingers, as shown by recent comments from two big supporters of US President Donald Trump.

If America was being bombed day and night because of something horrific our government did, and many innocent Americans and American children were being killed and traumatically injured, and we begged for mercy, but the rest of the world said,

“Americans voted for their...

— Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene (@RepMTG) August 23, 2025

Far-right Republican Congresswoman Marjorie Taylor Greene recently called Israeli actions in Gaza "genocide". In a social media post, she highlighted that "every US taxpayer is contributing to Israel's military actions," adding: "I don't want to pay for genocide in a foreign country against a foreign people for a foreign war that I had nothing to do with."

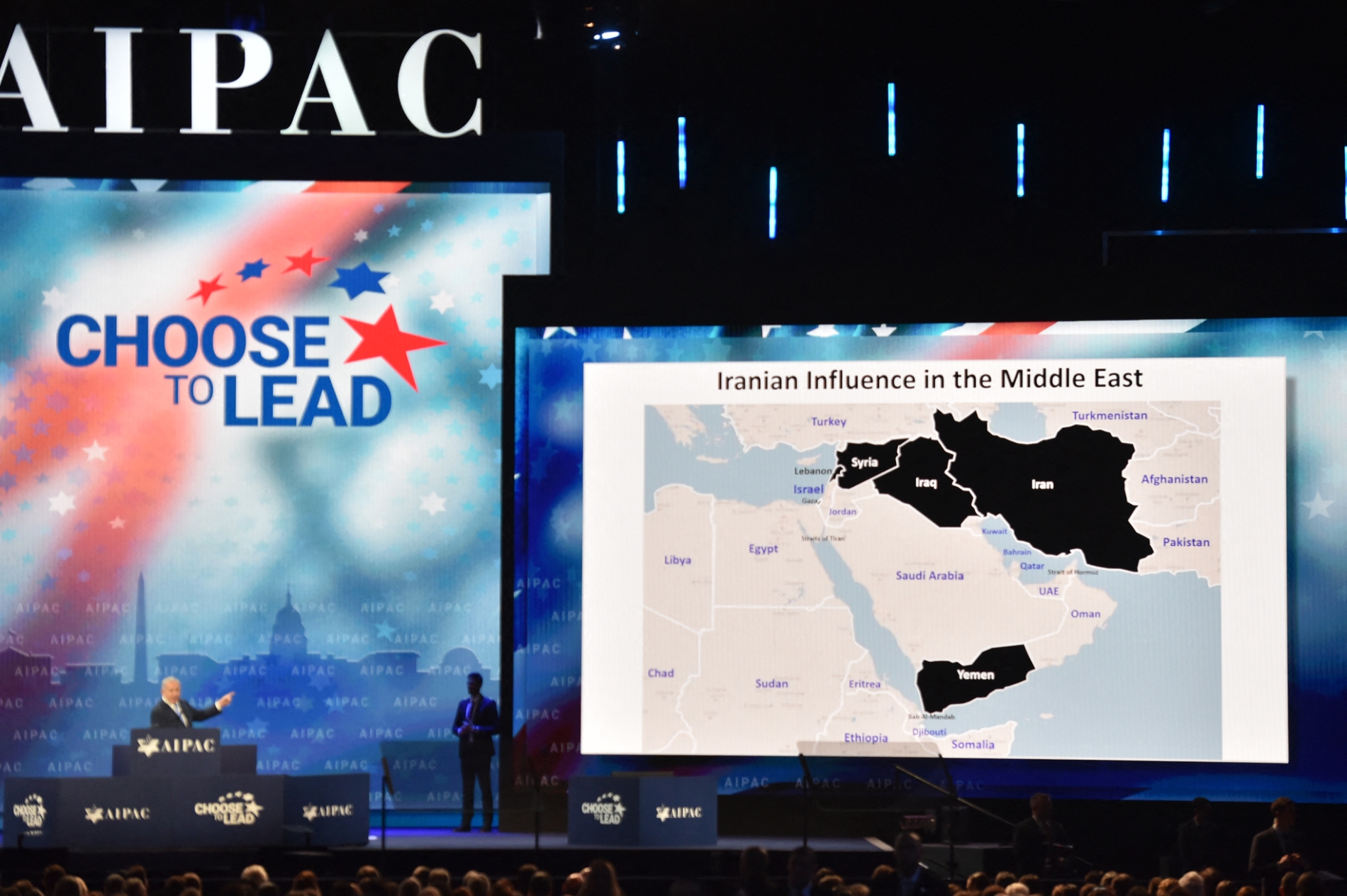

Likewise, former Fox News anchor Tucker Carlson openly criticised Israel's primary lobby group AIPAC (the American Israel Public Affairs Committee) and its influence in Congress, saying: "They're lobbying on behalf of a foreign government." Taken together, it shows how Trump's support base—commonly known as 'MAGA' in reference to Trump's election campaign slogan to Make America Great Again—is increasingly split on Israel.

Control and commitments

It is too early to tell whether this is the beginning of a rupture. So far, all indications are that the US is going along with Israel's vision for regional security, even though this requires more US commitment, not less. With Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu having recently reaffirmed his adherence to the vision of a 'Greater Israel' (i.e. expanded territory), the question, increasingly, is whether the US public will remain supportive.

Read more: Time to worry? Netanyahu says he ‘connects’ to a Greater Israel

Israeli hegemony does not necessarily mean direct physical control of territory. It may mean the domination of a region economically, while retaining the ability to intervene militarily with impunity. This appears to be Israel's current strategy. The risk (for Tel Aviv) is that it overreaches, demands more US support than the American public is willing to provide, and policy in Washington changes as a result.

A key question in all of this is whether Arab states can articulate an alternative vision for regional security that commands the support of the US, China, Russia and Europe. Such an alternative would mean Israel accepting that it has equal partners in the region, with whom it can work to establish a security architecture that takes account of the interests of all parties.