The global economy is undergoing profound and consequential transformations, driven by international policy choices, technological change, and demographic shifts. Amid population growth, changing labour markets, innovation, and environmental pressures, a critical question arises: where is the global economy headed?

These developments reflect the cumulative effect of changes that have been unfolding for more than a decade. Ongoing transformations in communication, media, technology, production processes, and labour markets are having a profound impact on economic productivity, job structures, and income distribution worldwide.

These shifts, accelerated by digital access and the adoption of artificial intelligence, are reshaping how work is performed and where value is created, often displacing routine tasks while creating demand for advanced skills. This is not the product of a single year, but a continuation and consolidation of trends that have been taking shape over time.

The world is moving toward social and economic conditions unfamiliar to those that prevailed in the 1950s and 1960s. These shifts are likely to give rise to differing political systems, with far-reaching economic consequences. Technological change has altered patterns of production, while the increasing use of artificial intelligence has begun to replace human labour in industry and agriculture. At the same time, the service sector has expanded rapidly, accounting for a growing share of GDP in advanced economies and absorbing the bulk of their labour force.

Such changes have inevitably affected education systems, which are under pressure to adapt in order to supply labour suited to evolving economic needs. These transformations have also reshaped the global industrial landscape, strengthening the position of some countries while weakening that of others.

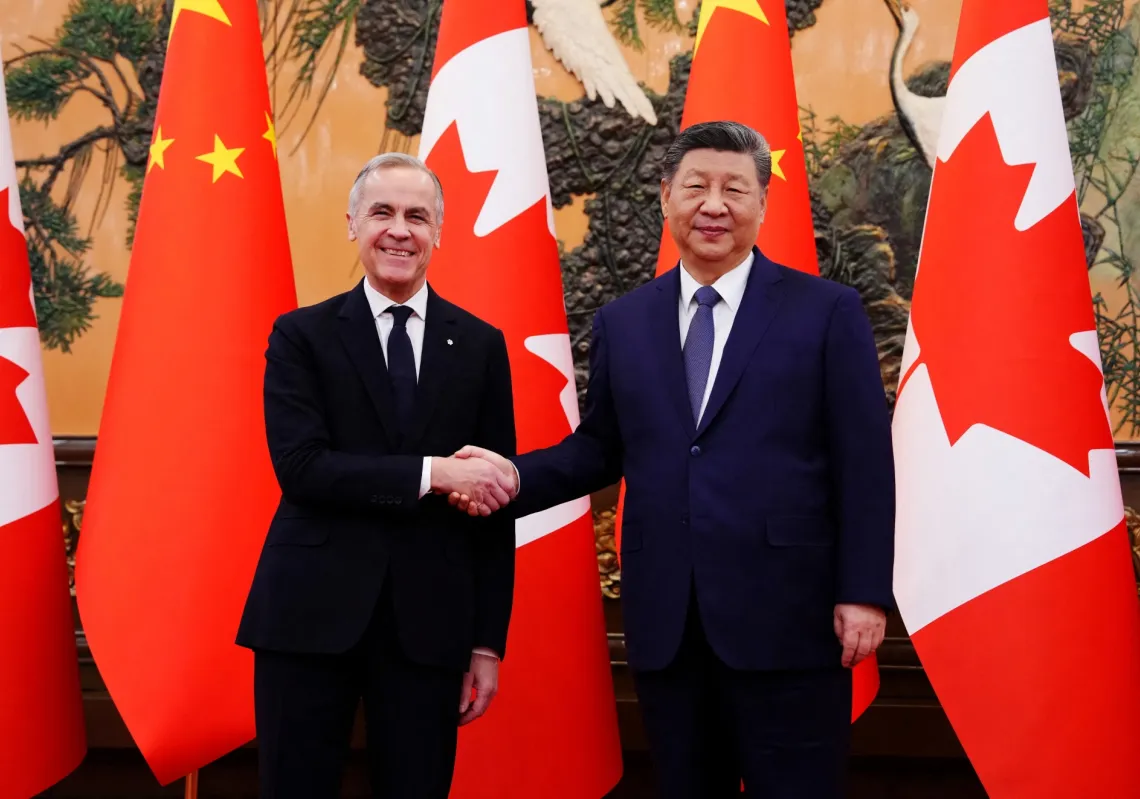

China's rise

China’s rise to become the world’s second-largest economy after the US illustrates the scale of these shifts and their structural impact on the global economy. Its economic output was projected to reach $19.4tn by the end of 2025, making it the second-largest contributor to global GDP. The US remains in first place, with an estimated GDP of $30.6tn, followed by Germany, Japan, and India. These aggregate figures, however, require careful interpretation.

When measured by per capita income, the differences are stark: annual income per person stands at around $89,600 in the US, $13,800 in China, $34,700 in Japan, and $2,800 in India, and nearly $60,000 in Germany. These disparities point to significant variations in living standards and consumption capacity.

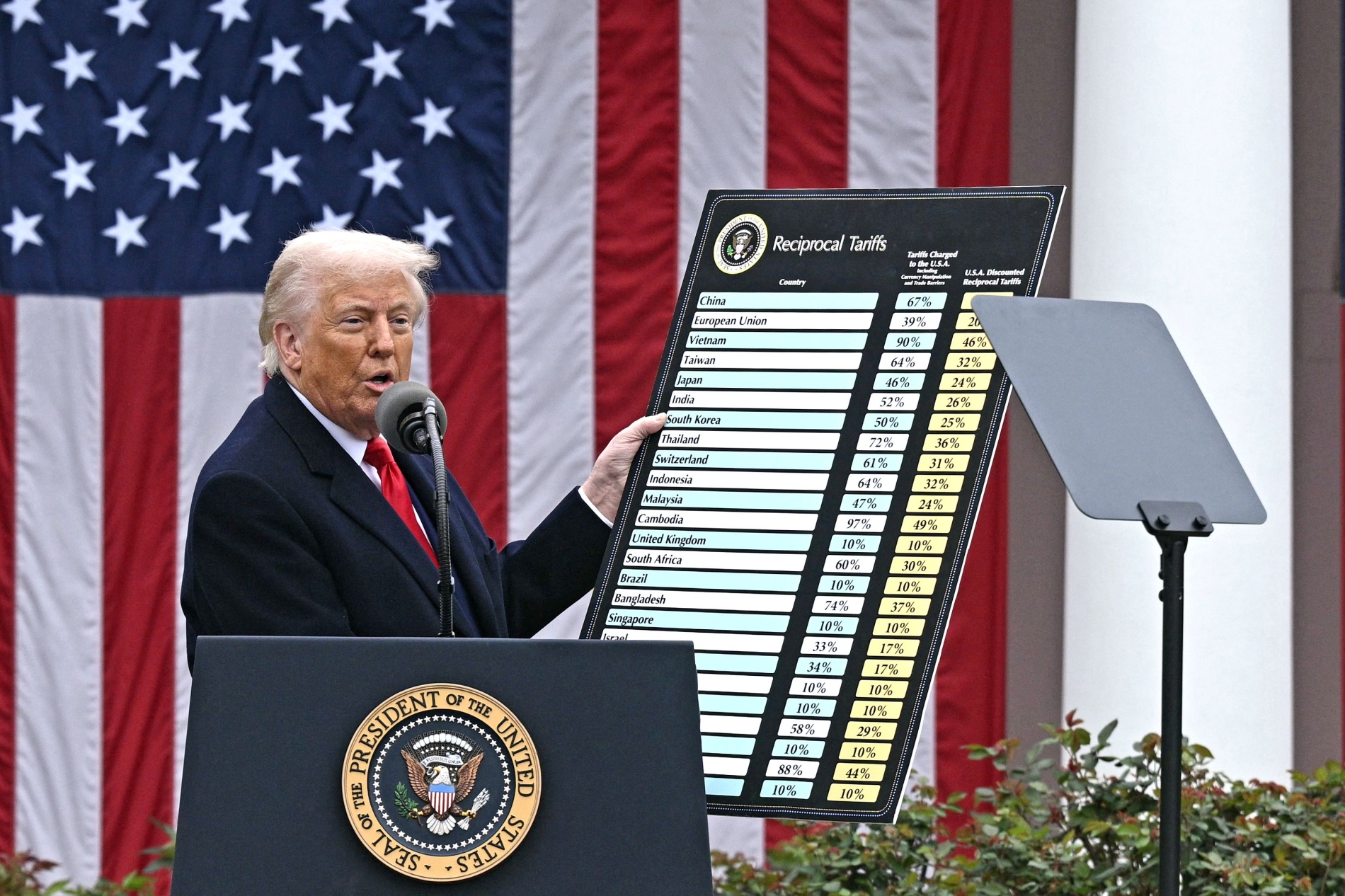

China continues to rely heavily on exports as a source of state revenue, while domestic consumption remains well below levels seen in the US, Japan, and major European economies. Alongside Japan and South Korea, China has secured strong comparative advantages in manufacturing, while the US and several European industrial economies have relinquished much of their manufacturing edge over the past few decades.

As a result, Western economies have become increasingly dependent on imports of essential goods and durable products from China and other Asian countries.

Potential demographic challenges

For several years, many industrialised nations have expressed growing concern about declining population growth and fertility rates that no longer meet the demographic replacement threshold (estimated at 2.1 births per woman of reproductive age). These trends have increased the proportion of people aged 65 and above and reflect broader changes in economic life that have reshaped social values, particularly in urban centres, which now accommodate the majority of populations in advanced economies and, to a considerable extent, in developing ones as well.

China, which pursued strict family planning policies under Mao Zedong during the 1960s and 1970s, most notably through a one-child policy, is now facing the consequences of prolonged demographic contraction. In recent years, it has sought to reverse course by introducing measures to encourage marriage and childbirth. This challenge, however, is not unique to China’s roughly 1.4 billion people. The US, most European countries, Japan, South Korea, and several Latin American nations are experiencing comparable demographic pressures.

At the global level, the world's population is projected to reach 8.2 billion by 2025, placing increasing strain on natural resources (water, food, energy) and the environment. Such strain generates a range of economic and social challenges, including congestion, overcrowding, and housing shortages in both urban and rural areas, especially in the megacities of Asia and Africa.

At the same time, slowing population growth raises concerns about labour market constraints. In the US, restrictive immigration policies pursued during President Donald Trump's first term have contributed to shortages of low-skilled labour, particularly in agriculture, hospitality, and other service sectors that, for decades, relied on migrant workers from Latin America willing to accept relatively low wages. Japan, which has historically resisted large-scale immigration, faces a similar dilemma as declining workforce participation coincides with rapid population ageing.