Along both shores of the Red Sea and the adjoining Gulf of Aden, several littoral states are in crisis. On the North African side, Sudan and Somalia both have huge problems, while on the Arabian Peninsula, Yemen is faring no better. These crises are not separate. They amount to one much bigger crisis playing out in three forms.

At its core, this is a crisis of the state, or rather, the absence of the state. In each of the three countries, the authority of the state has been eroded to the point that there is no longer any meaningful control of the territory, either in part or in whole. Combined, their coastlines along these most sensitive waterways measure around 5,300km, which is only slightly less than the distance between Moscow and Beijing.

These sovereignty vacuums give an opening to opportunists keen to interfere for leverage and gain. Unless this danger is challenged, the region will remain trapped in a cycle of denial and destruction, with instability from Bab al-Mandab to the Suez Canal.

The Red Sea is no longer just a global shipping route enabling the passage of goods and energy between Europe, Asia, and the Gulf. Today, it has become a reflection of state collapse along its shores. When the state falls or fractures, the sea no longer serves as a natural boundary or border that protects sovereignty; it becomes an instrument of pressure, a tool of blackmail, and an arena for a black-market economy.

Today’s problems are no geographical coincidence. Rather, they are a direct political outcome of efforts by actors with agendas. That outcome is long coastlines with no central authority to police them, no state institutions with a monopoly over the use of force, and war economies that feed on chaos and disorder.

A splintered Yemen

In Yemen, the sea is no longer on the margins of the conflict; it is part of it. Bab al-Mandab, a narrow chokepoint controlling one of the world’s most vital trade arteries, has been held hostage by the Yemen-based Houthi militia, which currently controls the Yemeni capital, Sanaa. More broadly, the Strait is held to ransom by armed non-state actors taking advantage of internal disputes and political fragmentation. In essence, they have put a chokehold on the maritime chokepoint.

The Houthis are not Yemen’s only problem. In the south, secessionists have been greatly encouraged by foreign assistance, to the point late last year that Aidarous al-Zubaidi, the former head of the Southern Transitional Council (STC), ordered his forces to seize several strategic governorates controlled by the internationally legitimate state authority, whose representatives were simultaneously forces out of Aden.

Yemen’s problems are therefore no longer confined to missiles or boats; they stem from the collapse of the very idea of the state, which in turn endangers navigation and prolongs the suffering of millions. The confrontation waged by the legitimate government (represented by the Presidential Leadership Council) and its National Shield Forces against the secessionists cannot be read outside this context. The swift action to contain the STC signalled a new alignment against the militias.

Somalia and Sudan

In Somalia, the same equation reappears in another form. The country has one of Africa’s longest coastlines, a weak central state based in Mogadishu, competing authorities, and armed groups who engage in smuggling and piracy. This leaves the coast ungoverned, the law unenforced, and the ports a target for militias.

Just as in Yemen, Somalia is dealing with a secessionist entity that claims control of the territory known as Somaliland. This entity has declared itself a state and was recently recognised as such by Israel, the first UN member state to do so. This rang alarm bells for other states in the region, not least Egypt. Why, Cairo asked, was a Somali secessionist entity being supported both diplomatically and practically?

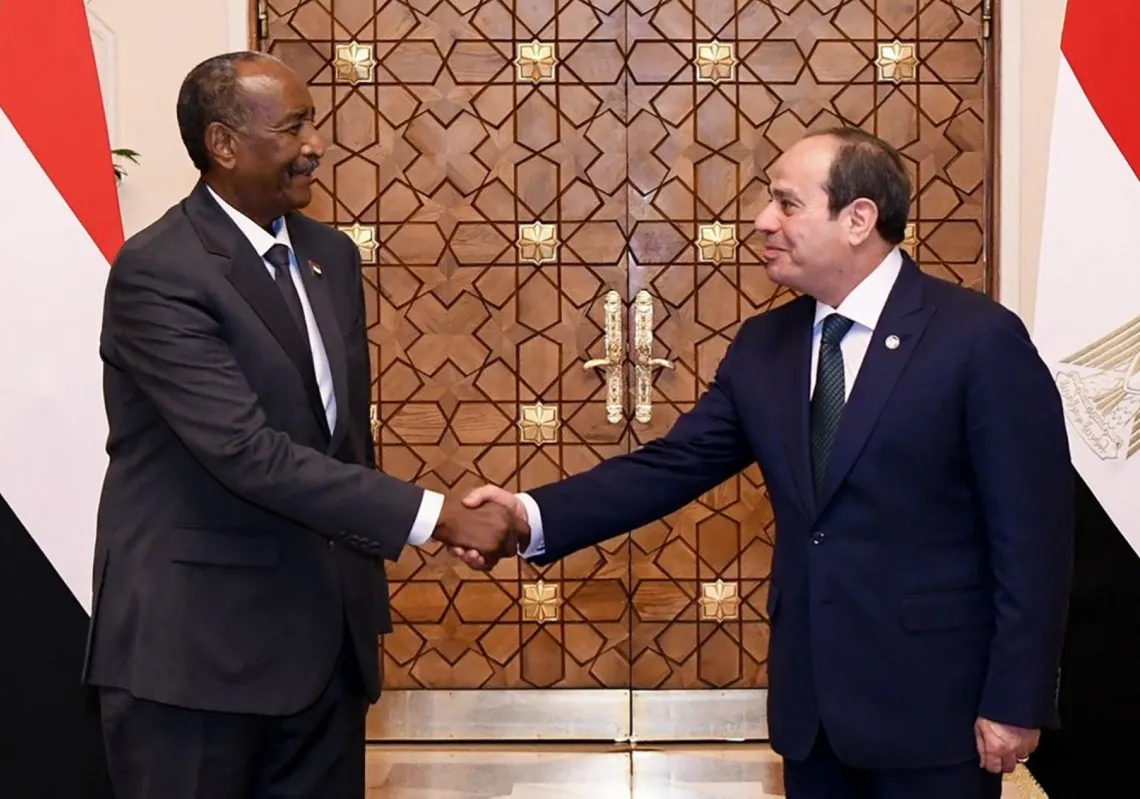

In Sudan, a brutal civil war approaching its third year has led to a crisis that now reaches beyond its borders. Africa’s third-largest country (and the 16th-largest country in the world), Sudan’s size, history, and strategic location mean that when it begins to break apart, the consequences are not contained domestically. In this case, they spill across the entire African shore of the Red Sea.

A state with no authoritative centre means porous borders, weapons smuggling, looting, and coastlines that become launchpads for aggressive action. In short, when the state collapses on land, stability at sea also collapses.