French jurist Monique Chemillier-Gendreau has devoted her career to international law and state theory. In May last year, she appeared before the International Court of Justice (ICJ) as legal counsel for the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation during public hearings convened at the request of the UN General Assembly, which sought an advisory opinion on Israel’s obligations as an occupying power.

Al Majalla caught up with Chemillier-Gendreau to discuss her latest book, Making a Palestinian State Impossible: Israel’s Objective Since Its Creation. Published by Textuel in May last year, the book analyses how Israel has methodically undermined the possibility of a Palestinian state since its establishment in 1948.

During a wide-ranging discussion, Chemillier-Gendreau assesses the compatibility of UN Resolution 181—the 1947 Partition Plan for Palestine—with the core principles of international law; the ICJ’s 19 July 2024 advisory opinion declaring Israel’s occupation of Palestinian territories (including East Jerusalem) unlawful; responsibility for Gaza’s reconstruction; and the current status of international law.

The professor emerita of public law and political science at Paris Diderot University (now Paris Cité University) believes the UN is effectively defunct, though she does not advocate for its immediate dismantling. “The absence of any structure would be worse,” she warns. Instead, she calls for the preparation of a new institution. “It should be called the World Organisation of Peoples—not of states.”

Below is her interview with Al Majalla.

What are Israel’s primary reasons for opposing the establishment of a Palestinian state?

This is a central and profoundly important question. In addressing it, one must distinguish between the stance of the Israeli government—that is, those who have held power for a very long time—and the views of the Israeli public. These are two separate matters. While they may lead to the same outcome, the underlying motivations differ.

Read more: Netanyahu centres reelection bid on burying two-state solution

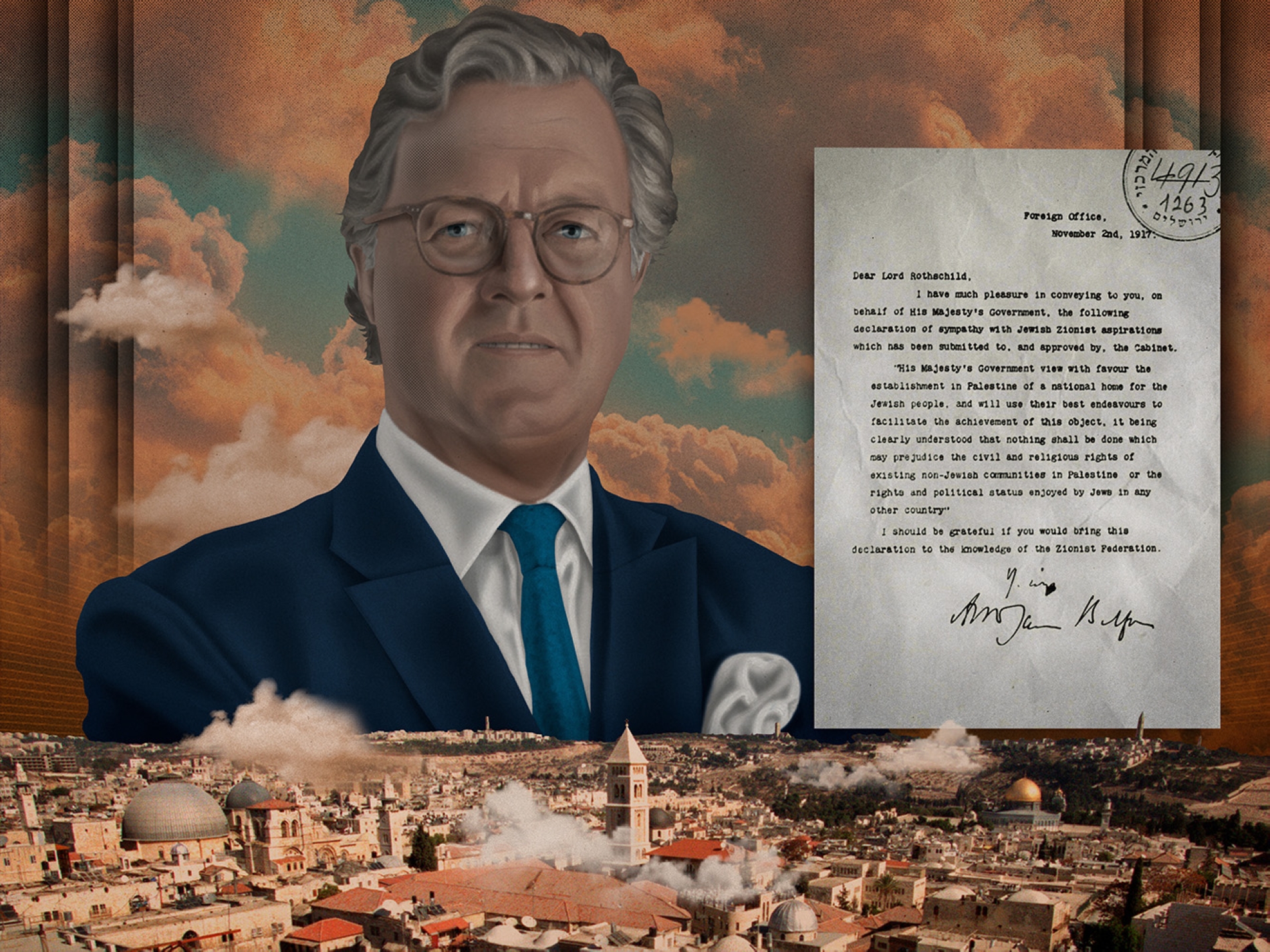

The position of the Israeli government is one of outright rejection of a Palestinian state, a stance that is no longer concealed but now openly declared. From the beginning—with the emergence of the Zionist movement in the late 19th century, the Balfour Declaration of 1917, and the eventual establishment of the State of Israel—there was no room, in the minds of the Zionist leaders who came to power, for a Palestinian state.

The Zionist project was built around a map drafted by the Zionists themselves, circulated from the moment they envisioned the creation of Israel. This map encompassed not only present-day Israel and Palestine but also parts of Syria, all of Jordan, and reached southward into Egypt. This vision became known as Greater Israel. It was driven by biblical and messianic impulses, an attempt to reconstitute the Kingdom of David, whose precise borders no one can define with certainty. This was the vision of Israel’s leadership. At no point were they sincere when the question of a Palestinian state was raised.

They accepted Resolution 181 because it presented a rare opportunity to secure recognition of the ‘Jewish national home’ mentioned in the Balfour Declaration—a concept that had previously been vague in legal terms. Suddenly, with Resolution 181, that Jewish national home, which had expanded during the British Mandate with the complicity and responsibility of Britain, became an actual state. Thus, they accepted the resolution because it served their interests and were, in fact, pleased when the Palestinians rejected it. The Arab states made tactical errors at the time, and the question of a Palestinian state was left suspended and neglected as a result.

During the Oslo period of the 1990s, I do not believe the Israeli government ever genuinely intended to establish a Palestinian state. The evidence lies in the fact that the Palestinian Authority was never granted sovereign powers. What it received was not sufficient to form the foundation of a state.

The Israeli public, however, presents a different picture. I believe that a segment of Israeli society—during the Oslo years, for instance—participated in the process in good faith. The presence of figures such as Yitzhak Rabin attests to this. A portion of Israeli society, particularly among modern, educated circles, believed the process was credible and that peace could eventually be achieved.

However, this public was shaped by the ideology of its leaders, an ideology rooted in an obsession with security, without understanding that Israeli security will never be assured except through the establishment of a Palestinian state. Nothing other than a Palestinian state can calm the Palestinians or eliminate the sources of violence.

Read more: Trump's 'grand peace' doesn't tackle root causes

Do you believe Resolution 181 was compatible with the fundamental principles of international law?

The answer is a complex one. Resolution 181 was adopted in 1947, when the UN Charter had been in existence for only two years. The legal framework that the UN would later develop around the right of peoples to self-determination had not yet fully taken shape. The charter itself was ambiguous on the issue of decolonisation, for a clear reason: it had been drafted primarily by the major Western powers, among them the leading colonial empires of the time, such as France, Britain, Portugal, and others.

The charter does affirm the principle of self-determination in its general provisions and in Article 1. Yet, when it comes to colonised peoples, Chapter XI, titled ‘Declaration Regarding Non-Self-Governing Territories’, does not enshrine independence as a core principle. Instead, it stipulates that administering powers must govern these territories for the benefit of their inhabitants, without committing to their liberation, while requiring them to submit an annual report to the secretary-general.

When the question of Palestine was brought before the UN, the legal texts establishing the right to decolonisation had not yet been developed. Those would come later, through armed resistance—the Vietnamese in the Indochina War, the Algerians, and the peoples of the Portuguese colonies. These were the great liberation movements that helped reshape international law.

So, I cannot offer a definitive answer to your question. The Palestinian people were a colonised people under the Ottoman Empire, to which Palestine had belonged. After the First World War and the defeat of Germany and the Ottomans, the Treaty of Versailles determined that the victorious powers would administer former Ottoman territories under the Mandate system.

One point that might permit a cautiously affirmative answer is that the Mandate system explicitly stated that Class A Mandates—those applied to former Ottoman territories—were intended to guide their peoples towards independence. This was clearly articulated in both the Covenant of the League of Nations and the Mandate instruments themselves. This is what took place in Lebanon, Syria, and other countries that emerged from the Mandate in the aftermath of the Ottoman Empire. One may therefore argue that Resolution 181 did not adhere to what had been outlined by the Mandate system. That would be a fair way to frame the issue.

Read more: What Arthur Balfour's grandnephew gets wrong

What complicates matters further is that the Jews and Zionists, supported by British complicity via the Balfour Declaration, claimed a right to self-determination as well. This claim presents a deep paradox. In modern international law, the right to self-determination belongs to a people living on its own land yet subject to the authority of another power, and seeking liberation on that same land. The Jewish people, however, did not possess a land. They constructed one for themselves by asserting their presence on the land of Palestine.

Thus, we were faced with two competing claims to self-determination. One was the Palestinian claim, rooted in a clear legal framework: the Mandate for Palestine, whose terms were explicit, and the later development of the UN’s self-determination doctrine. The other was the so-called Jewish right to self-determination, a claim lacking any clear legal basis. The answer, therefore, is both precise and nuanced. International law at the time had not yet matured into a settled and coherent set of standards.