In the basement of the Musée de l’Homme (The Museum of Man) rest more than 18,000 skulls, collected from across France’s colonial empire—many of them from Algeria. One skull caught the attention of Xavier Le Clerc, a French writer of Algerian descent.

It was the skull of a little girl, no more than seven years old, who might once have been running along the slopes of Kabylie or carrying a clay jar of water from a spring, before a French officer stopped her with his sword. She did not die on a battlefield, but in the courtyard of her burned village. Her head was carried to France to enter the 19th-century trade in “science,” where skulls were bought and sold to “prove” racist theories of European superiority.

In his novel The Bread of the French, Xavier Le Clerc (Hamid Aït Taleb) does not merely recount this historical tragedy; he also explores its profound impact. He creates an intimate dialogue with the girl, imagining her life and deciding to name her Zahra. The choice is deliberate: a refusal to let her remain just a number in a wooden box. “Zahra, you will leave these catacombs, I promise you. You will return to the soil from which you were taken,” he writes, as though sealing a literary and moral pact with her.

The stolen loaf

The title is the first key to the novel's symbolism. Bread, on the surface, is a daily staple, but here it represents life, rights, and dignity. The story opens with a stinging line the author once heard in a Normandy bakery: “We don’t sell the bread of the French to bonnious (derogatory racial slur)! Ten loaves! And what next?” The insult places the reader in a direct continuum from the 19th-century colonisation of Algeria to contemporary France.

Colonial rule was not just military occupation; it was the systematic plunder of land and resources, redistributed according to racial hierarchy. In Algeria, fields were planted to feed the French army while local farmers starved. Decades later, Algerian migrants in France were treated as outsiders, allowed to do the most menial and difficult jobs, yet denied their share of the "Bread of the French".

Le Clerc structures the narrative on a parallel axis: the bread stolen from Algerian farmers’ tables and the bread denied to their migrant descendants in French cities are two sides of the same coin. In the novel, the loaf is not just flour and water; it is borrowed from a stolen history and a hungry memory.

The imagery subtly recalls the classic French comedy sketch Le Douanier by Fernand Raynaud, which lampooned the notion of “French bread” as a metaphor for deep-seated xenophobia, particularly in its famous opening: “I’m not stupid. I’m a customs officer, and I don’t like foreigners. They come to eat the Frenchmen’s bread.”

A childhood turned icon

Zahra is not a conventional fictional character; she is an icon, embodying the fate of thousands of victims of colonial violence. In imagined conversations with her, the author fuses his own biography with modern Algerian history.

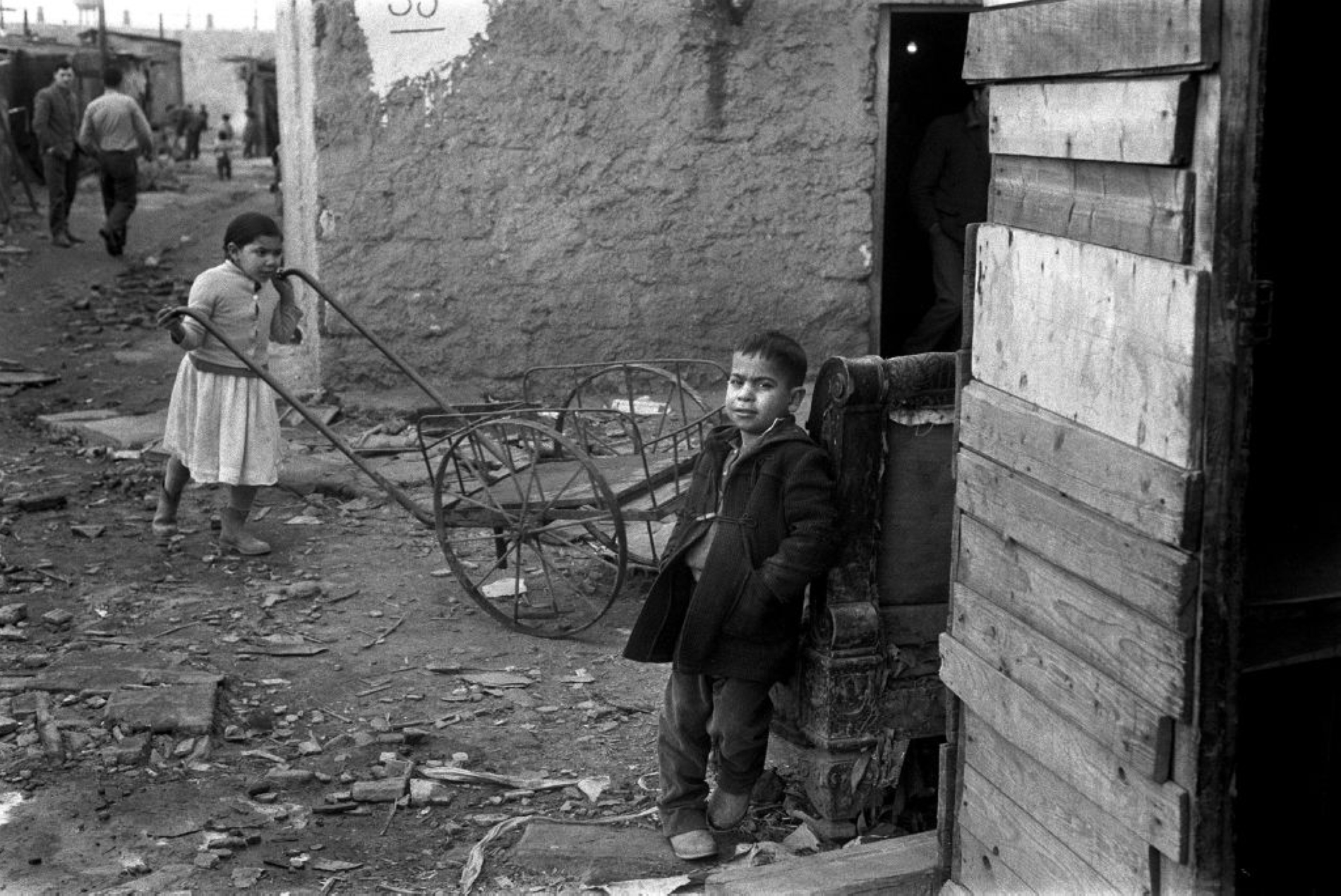

Le Clerc—himself, the son of an immigrant family—recounts the daily humiliation he experienced growing up: “These people never did their homework in the doorway of a broken elevator, in the smell of urine... They never grew up with eight brothers and sisters,” he recalls in an autobiographical aside. By merging these threads, the novel becomes a bridge between the Parisian basement of skulls and the shabby lift in a French banlieue.

In this blending of the personal and the historical, Le Clerc pays homage to Umberto Eco’s narrative style— intertwining intimate storytelling with cultural critique. Zahra is not just there to be mourned, but to probe a larger question: how can one dismantle a colonial legacy still very much alive in city maps, district names, and even in the way bread is sold?