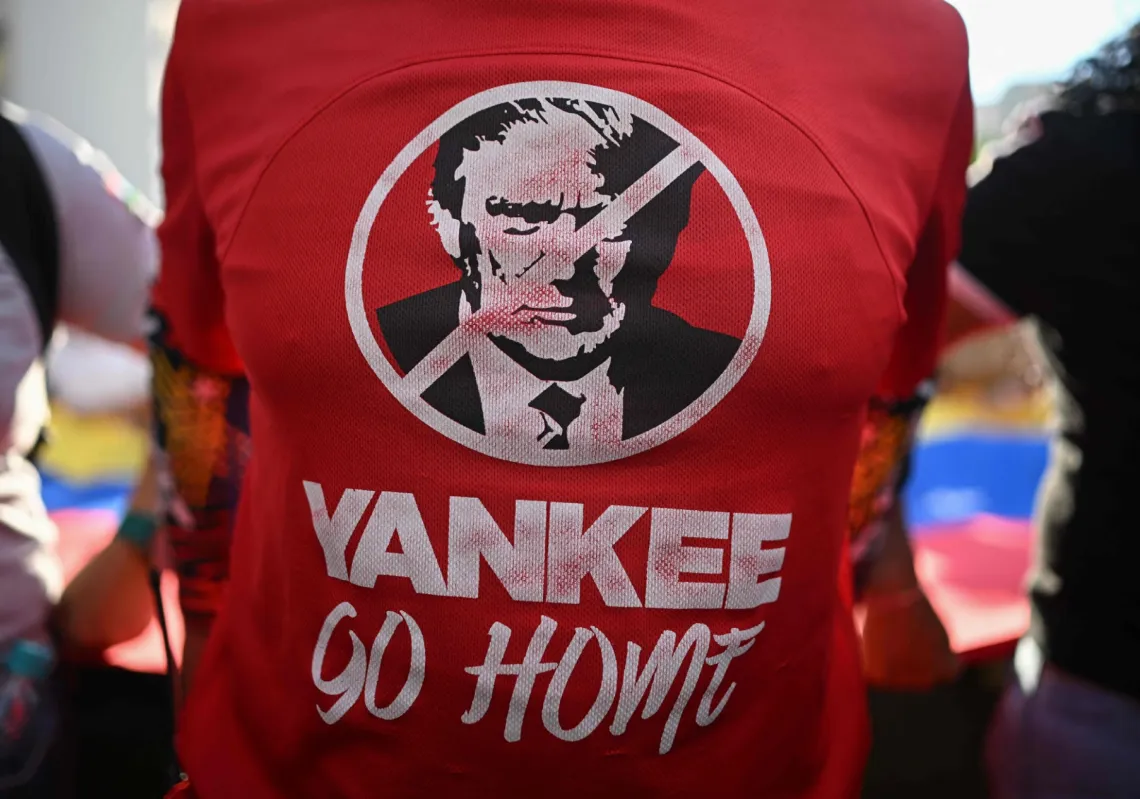

By attacking Venezuela, seizing its president, and promising to “run” the country indefinitely—all without any congressional or United Nations authorisation—US President Donald Trump may well have shredded what little is left of international norms and opened the way to new acts of aggression from US rivals China and Russia on the world stage, some experts say.

In return, Trump probably achieved little in the way of stopping narcotics flows into the United States, even as he asserts what he calls the “Trump corollary” to the Monroe Doctrine in his new National Security Strategy, which aims “to restore American preeminence in the Western Hemisphere.”

While it’s true that much of the world and, by most accounts, a majority of Venezuelans did not see President Nicolás Maduro as legitimate—and Maduro has been indicted in the United States on charges of being a drug trafficker—Trump has now set a potentially devastating precedent, some critics and experts say. Beijing and Moscow could decide to act in similar fashion against regional leaders whom they deem to be threats—especially in Ukraine and Taiwan—all without worrying about the legitimacy of such actions.

“If the United States asserts the right to use military force to invade and capture foreign leaders it accuses of criminal conduct, what prevents China from claiming the same authority over Taiwan’s leadership?” Democratic US Sen. Mark Warner, the vice chairman of the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, said in a statement. “What stops Russian President Vladimir Putin from asserting a similar justification to abduct Ukraine’s president? Once this line is crossed, the rules that restrain global chaos begin to collapse, and authoritarian regimes will be the first to exploit it.”

At a news conference on Saturday announcing what he called “one of the most stunning, effective, and powerful displays of American military might and competence in American history,” Trump made clear that his goal was regime change—and even long-term US occupation. This in spite of the administration’s repeated denials that this was his goal; Trump ran for president in 2024 on a platform of avoiding such interventions.

“We’re going to run the country until such time as we can do a safe, proper, and judicious transition,” Trump said, and he did not deny suggestions from reporters that this could require years. In a haunting echo of similar claims made more than two decades ago before the US invasion of another oil-rich nation, Iraq, Trump said that any US costs would be reimbursed by “money coming out of the ground”—in other words, Venezuelan oil. “We’re going to be taking a tremendous amount of wealth out of the ground,” Trump added.

“We can’t take a chance that somebody else takes over Venezuela,” the US president said. He said that US oil companies would now be sent in to fix things and restore “American property” that he contends was confiscated, as well as “make the people of Venezuela rich, independent and safe.”

Asked if the occupation would involve US troops, Trump said, “we’re not afraid of boots on the ground if we have to.” In other remarks Saturday, the president also suggested that he could soon move militarily against Mexico and Colombia—telling reporters that Colombian President Gustavo Petro has to “watch his ass.”

Speaking to Fox News, Trump said that despite his good relations with Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum, “She’s not running Mexico. The cartels are running Mexico,” adding that “something’s gonna have to be done with Mexico.”

It is noteworthy that more than two decades ago, President George W. Bush’s invasion and occupation of Iraq was seen as a huge blow to the legitimacy of international law; indeed, Putin has cited it as a justification for Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Yet even in that case, the Bush administration sought UN Security Council authorisation, while Trump and his team have not bothered to do so.