For more than a century, the United States has attempted to shape political outcomes across Latin America, whether that be backing coups, toppling governments, or supporting authoritarian figures aligned with its strategic interests. Few of these efforts produced the stability sought in Washington. Instead, they have destabilised societies, strengthened autocrats, and entrenched the idea that external threats were a permanent feature of the region’s politics.

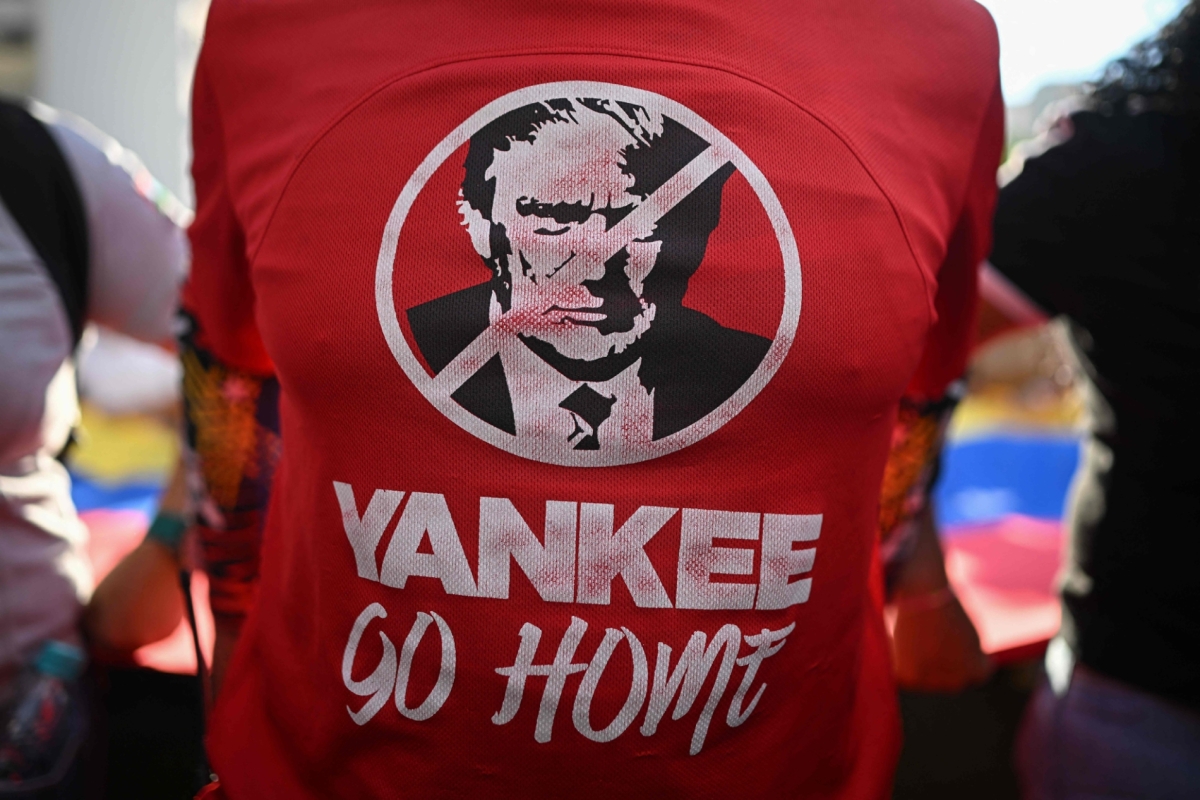

With parts of the US political right now reviving anti-regime rhetoric against Venezuelan leader Nicolás Maduro, the past has returned to relevance. The question is not whether intervention is possible, but why it has consistently failed, and why Latin America has learned to distrust it so deeply.

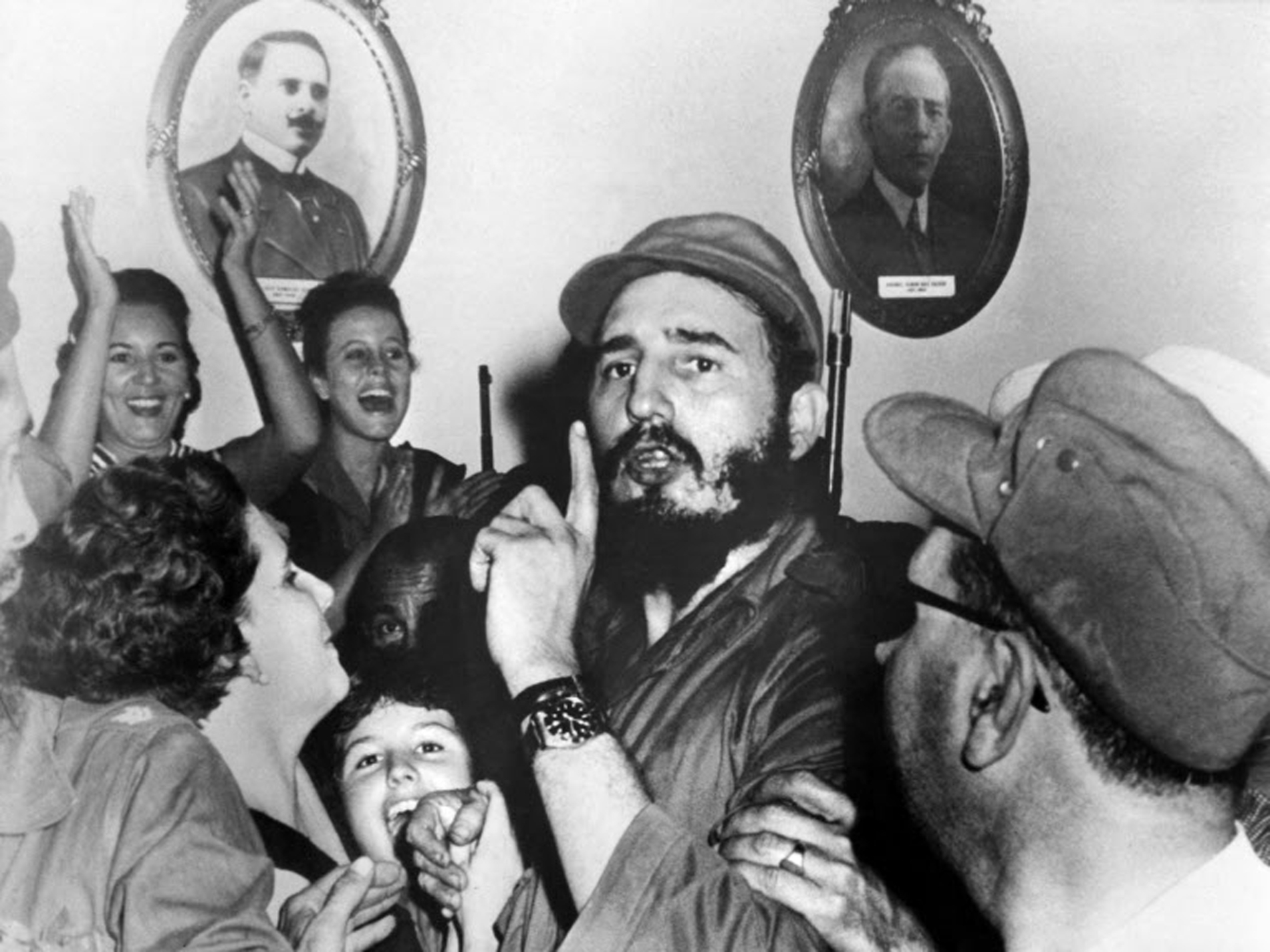

The story begins well before the Cold War. Between 1898 and 1934, the US occupied Cuba, Puerto Rico, Haiti, the Dominican Republic, and Nicaragua, often justifying invasions as moral necessities to restore order. What emerged instead were long periods of military rule, financial controls, and political systems designed to serve US security and economic priorities.

Instability as threat

Some think these early occupations laid the groundwork for a pattern in which Washington came to see instability in the region as a threat that demanded direct political intervention. Historian and Latin America specialist Greg Grandin argues in Empire’s Workshop (2006) that Latin America became a laboratory for interventionist policy, shaping how the US came to understand both the world and its own imperial role. By the 1950s, that logic had hardened into doctrine.

In 1954, the CIA engineered the overthrow of Jacobo Árbenz in Guatemala, a democratically elected leader whose land reforms clashed with US corporate and strategic interests. The coup toppled the government but unleashed four decades of armed conflict and authoritarian rule. A UN truth commission later concluded that the intervention “produced the conditions for genocide.” Guatemala never fully recovered.

The pattern repeated itself across the region. Historian and military regime expert Carlos Fico documents how US support helped install a military dictatorship in Brazil in 1964 that remained in power for 21 years. Using declassified archives, investigative researcher Peter Kornbluh showed the extent of covert US efforts to destabilise Salvador Allende before Chilean generals seized power there in 1973. Augusto Pinochet’s dictatorship, backed diplomatically and economically by Washington, became one of the most repressive regimes in the continent’s history.

El Salvador, Nicaragua, and Honduras became Cold War battlegrounds, the US arming some factions while labelling others as communist threats. The result was not the triumph of democracy but prolonged civil wars, clandestine operations, and widespread human rights abuses. A clear throughline emerges, as interventions that promised stability often produced long-term disruption. Latin America’s political landscape repeatedly defied Washington’s expectations.

Oversimplifying reality

Several key dynamics help explain why intervention so often failed, and why it continues to shape regional reactions today. The US frequently framed conflicts as ideological, rather than social. Agrarian movements demanding land reform were branded ‘communist threats’ while nationalists seeking autonomy were interpreted as ‘Soviet proxies.’

By oversimplifying political realities, Washington backed leaders with little domestic legitimacy while underestimating the grievances that drove uprisings. Once installed, US-supported governments depended on repression, fuelling cycles of resistance and instability. Regime change removed governments but rarely replaced them with sustainable institutions. The fall of Árbenz generated chaos, the removal of Allende empowered a dictatorship, and military rule in Brazil ended with a fragile democratic transition still haunted by its authoritarian legacy.