For much of the second half of the 20th century, Venezuela and the United States were not just partners but close allies in security matters. In the context of the Cold War, when Washington sought to contain communism across the Americas, Venezuela was a reliable collaborator. Its strategic importance as a major oil exporter and its commitment to democracy after the fall of the dictatorship in 1958 made it a natural partner.

The partnership was built on training, military assistance, and trust. US advisers helped professionalise Venezuela’s armed forces and trained its pilots on American aircraft. Caracas was even allowed to purchase advanced weaponry, including F-16 fighter jets —a privilege not extended to most Latin American nations at the time. The countries also worked closely in counter-narcotics operations, with American officers stationed in Venezuelan bases and cooperating on intelligence and enforcement. Joint exercises such as the UNITAS naval manoeuvres symbolised the depth of the relationship.

Indeed, the relationship was so strong that the US military mission operated from Fuerte Tiuna, Venezuela’s principal military complex in Caracas. Few bilateral defence relationships in the hemisphere were as close. This period was marked by shared security priorities and a sense that both countries benefited from cooperation. Could anyone at the time have imagined that this deep military partnership would one day collapse into open hostility?

Enter Hugo Chávez

The election of Hugo Chávez in 1998 represented a dramatic turning point. The former army lieutenant colonel who had led a failed coup in 1992 came to power on a wave of popular support, promising to reshape political and economic systems. His vision—which he called “Bolivarianism”—aimed at strengthening state control over resources, pursuing a form of democratic socialism, and asserting Venezuela’s independence from what he regarded as US imperialism.

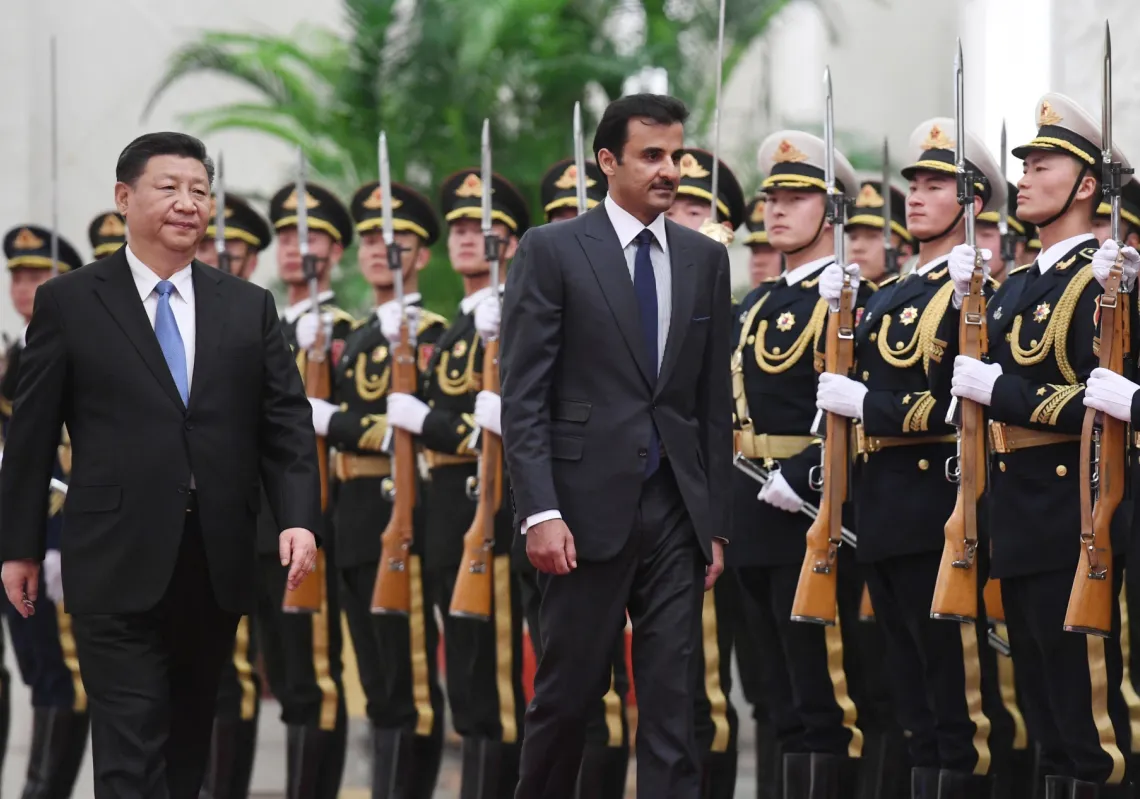

Chávez’s project involved forging closer ties with Cuba, building new alliances with Russia, China, and Iran, and advocating for a multipolar world where US influence would be checked by rising powers. In defence terms, this meant reducing dependence on Washington, diversifying arms suppliers, and reshaping the Venezuelan military to serve his revolutionary project.

Several pivotal moments defined the rapid breakdown of US-Venezuelan defence relations.

1999: US disaster aid rejected

Following catastrophic floods in Vargas state, the US deployed significant humanitarian assistance, including food, water, and purification equipment. Chávez initially accepted the aid but then rejected further US military involvement, citing national sovereignty. This decision marked the first major rupture in a partnership that had previously seemed unshakeable.

2001: Expulsion from military headquarters

Chávez ordered the US military mission to vacate Fuerte Tiuna, where it had operated for over five decades. This was a powerful symbolic act, signalling that the era of blind alignment with Washington was over.

2002: Coup attempt

A coup briefly removed Chávez from power, and the US quickly recognised the interim government of Pedro Carmona. Although Washington denied direct involvement, the perception that it had tacitly supported the coup severely damaged trust. Chávez accused the US of plotting his overthrow, deepening the adversarial tone of the relationship.

2004–2005: Joint exercises, drug cooperation end

Venezuela expelled US military advisers, ended its participation in joint exercises, and removed the US Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), alleging that it was spying. These moves dismantled the practical mechanisms of security cooperation that had been built over decades.

2005–2006: US arms embargo

In response, Washington imposed an arms embargo, blocking sales and maintenance of US military equipment, including the Venezuelan F-16 fleet (US Department of State, 2006). This pushed Venezuela to purchase helicopters, rifles, and aircraft from Russia, cementing its pivot away from US suppliers.

From this point onward, the two countries were on divergent paths. Was this an avoidable diplomatic breakdown, or was Chávez’s ideological project fundamentally incompatible with close relations with Washington?

Enter Nicolás Maduro

Chávez’s death in 2013 did not bring rapprochement. Nicolás Maduro, his chosen successor, inherited both the political project and its international posture. Yet his presidency coincided with Venezuela’s worst economic crisis in modern history. Plummeting oil prices, mismanagement, and sanctions led to economic collapse, hyperinflation, and mass emigration.

The US response under President Donald Trump was to ramp up the pressure. Washington openly supported opposition leader Juan Guaidó, recognised him as interim president, and imposed sweeping sanctions targeting Venezuela’s oil sector and senior officials. Washington's desire for regime change was no longer a quiet undercurrent but an explicit policy objective.

Military-to-military relations—already frozen—became nonexistent. Instead, US attention shifted to supporting Venezuela’s neighbours in coping with the humanitarian crisis caused by the exodus of millions of Venezuelans. This was viewed by some as a strategic containment policy aimed at isolating Maduro to dial up domestic pressure.

A reading of US Southern Command posture statements between 2000 and 2023 shows that Venezuela was not a central focus for US defence planners for much of this period. Mentions of the country were relatively rare, with far greater emphasis placed on Colombia—especially in the context of counter-narcotics operations and the fight against insurgent groups such as the FARC.

When Venezuela was mentioned, it was often alongside Cuba and Nicaragua, reflecting a framing of the country as part of a broader bloc of states seen as antagonistic to US interests. References to rebuilding security cooperation were virtually absent, appearing only twice in more than two decades of official statements. It was only after Venezuela’s economic collapse under Maduro that the country began to be treated as a strategic threat.

Decline in military assistance and arms trade

US military assistance to Venezuela steadily declined from the late 1970s and collapsed after 2003. Programmes such as the International Military Education and Training (IMET), which allowed Venezuelan officers to train in the US, were discontinued. Counter-narcotics funding, which had once been substantial, fell from nearly $12mn in 1999 to almost nothing by 2012.

The arms trade followed a similar pattern. Venezuela had once been a key purchaser of US weapons, even receiving rare permission to buy F-16s in the 1980s. After the embargo of 2006, Caracas turned to Russia and China, making large-scale purchases of helicopters, fighter jets, and rifles. By 2007, Venezuela was the largest arms importer in Latin America.

More recently, Russia has sent nuclear-capable bombers to Venezuela, and Cuban intelligence advisers have been deeply embedded in the Venezuelan military.

Dangerous new phase

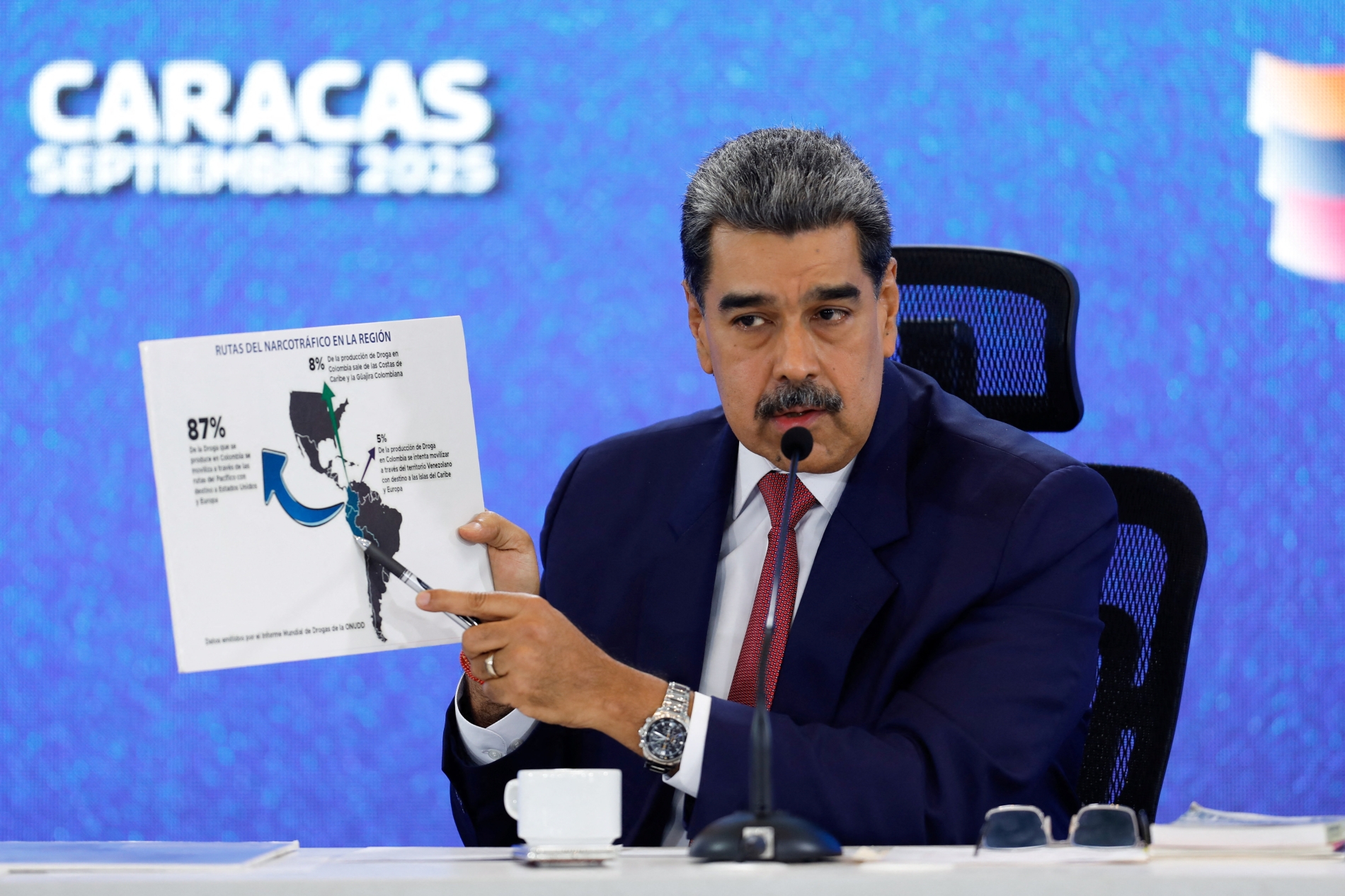

But relations between Washington and Caracas took a dangerous leap on 2 September after US forces struck a vessel in the Caribbean, killing 11 people. Washington claimed the boat belonged to the Tren de Aragua cartel and was transporting narcotics to the United States. President Trump released footage of the strike and authorised a $50mn reward for information leading to the arrest of Nicolás Maduro, whose 2024 re-election Washington continues to refuse to recognise.

Legal scholars quickly raised concerns, arguing that the strike may have violated international maritime law and human rights conventions, as it occurred in international waters and there is no formal state of war between the US and Venezuela. Analysts also noted that the US position on the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS)—while not formally ratified—commits Washington to act consistently with its provisions regarding freedom of navigation and lawful use of the high seas.

Undeterred, Washington ordered a second strike on 15 September, killing three more alleged traffickers. Trump insisted that US forces had “100% certainty” of the targets’ identities, claiming that evidence of drugs was found floating in the sea. He warned that further action, including potential strikes on Venezuelan soil, could follow.

Maduro’s government responded defiantly, framing the attacks as acts of aggression aimed at justifying regime change. Caracas deployed F-16 fighter jets to fly over a US Navy destroyer, accused US forces of illegally seizing a Venezuelan fishing boat, and called on citizens to join the civilian militia, with reports that public-sector employees were pressured to enlist.

From an international relations perspective, these actions can be understood as efforts to shore up a reputation for resolve. In an anarchic international system, states often seek to signal strength in order to deter future coercion. Caracas likely fears that failing to respond would embolden Washington to escalate its campaign, yet these steps also raise the risk of miscalculation and direct confrontation.

The strikes have sparked intense debate within the United States about presidential authority. Critics argue that Trump may have bypassed Congress in violation of the War Powers Resolution and question whether the legal basis for using force against a criminal organisation is sufficient. Supporters, however, have praised the strikes as strong action against what they call narco-terrorism. The administration maintains that its actions are lawful and necessary to protect national security.

These developments pose difficult questions. Are we witnessing the prelude to a direct clash between two nations that were once close allies? To what extent will the United States escalate its operations, and to what lengths might Venezuela go in order to assert its sovereignty and its international reputation?