Unburdened by academic jargon, Lebanese writer and poet Issa Makhlouf has caught the eye of the contemporary Arab creative scene. The author of The Eye of the Mirage is known for creating space within the text, but his new book—The Paris I Lived: A Journal—takes on a wholly different style, abandoning established norms and wisdoms.

Born in 1955, Makhlouf fled Lebanon in 1975, at the onset of the country’s civil war. He first went to Caracas, Venezuela, before settling in France, where he worked as an author, a radio news journalist, and a university professor in Paris. He has translated the works of others and penned several books of his own, including A Letter to the Two Sisters and The Solitude of Gold.

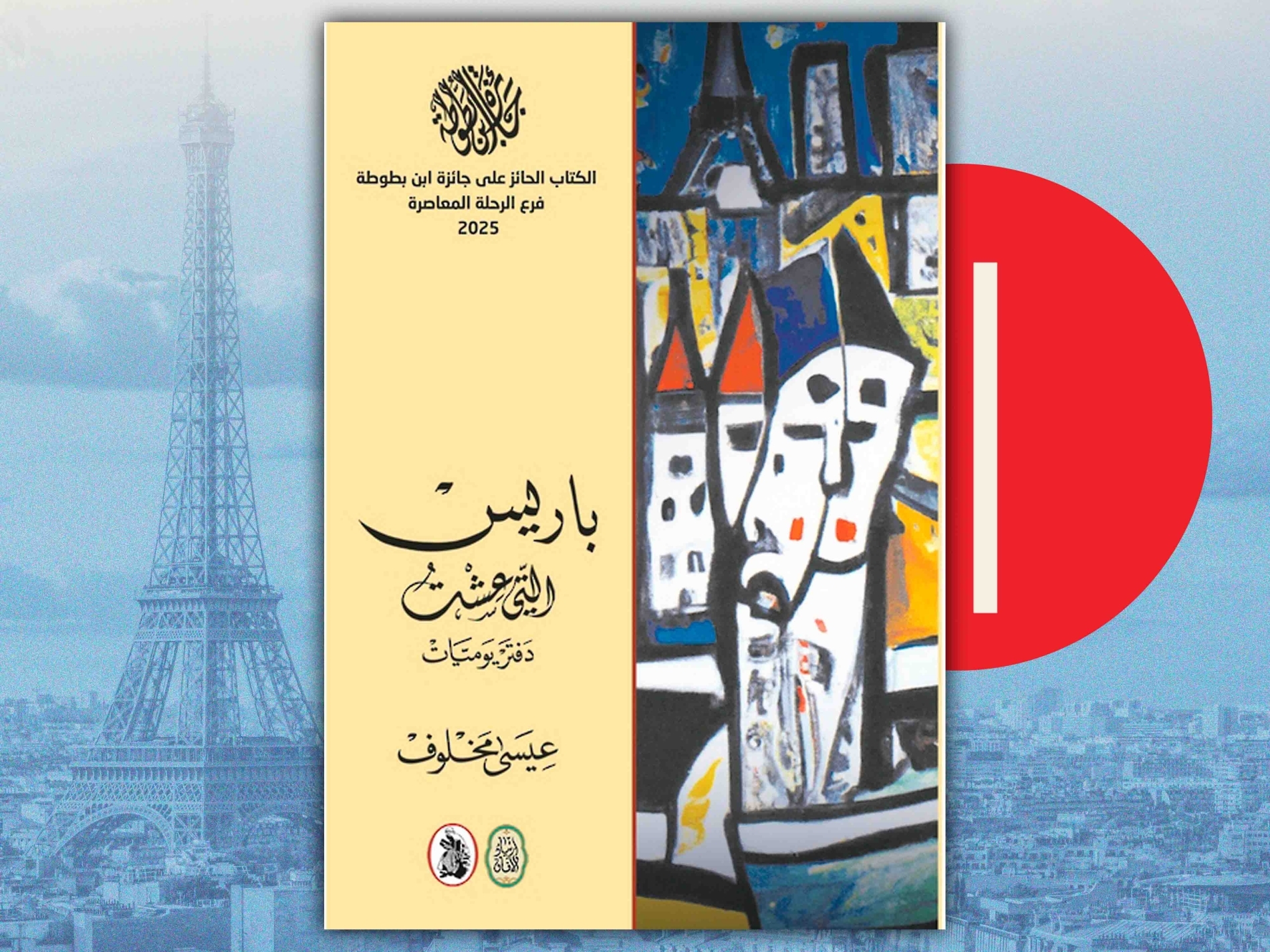

He won the French Max Jacob Literary Award in 2009 for A Letter to the Two Sisters, and this year he won the Ibn Battuta Award for Travel Literature for The Paris I Lived. His collections weave an intellectual fabric that both unsettles and challenges the reader, creating a sense of confusion between the images, signs, and symbols that Makhlouf employs across poetic works, prose, paintings, and sculptures. He recently spoke to Al Majalla. Here is the conversation:

With reference to your Paris journals, how can we best write about our own lives?

Our biographies are never created in isolation. They are shaped by the unique and shared circumstances of our childhood and upbringing, by time and place, by the events that accompany us, and by the people with whom we share our lives. It also encompasses a summary of our intellectual journey, our experiences, our travels, and everything we have read, seen, and felt over time.

The Paris I Lived is part of this broader understanding. It serves as an extension of two other books, The Apple of Paradise: Questions about Contemporary Culture and Other Banks. In these three works, the self is examined alongside the year and the transformations of the world, observing the reality of the city—which was the cultural capital of the world in the 19th century—and how it has changed in the era of globalisation and technological revolution.

I focused on the last two decades of the 20th century, when I arrived in Paris to study at the height of its cultural prosperity, and how—as a unique cultural beacon—it began to decline under the relentless pressures and brutal domination of capital.

What's your view of literary awards in the Arab world?

In recent decades, literary awards in the Arab world and beyond have become a phenomenon in their own right: simultaneously cultural, sociological, and economic. Examining their advantages and drawbacks reveals their true role within the literary and cultural landscape.

In the Arab world, awards—especially those for fiction—have become a driving force behind novel writing and book sales. In the West, where hundreds of thousands of copies of winning novels are sold, the financial stakes often outweigh the literary and aesthetic ones. Awards can promote a book and boost sales, which is important, but they cannot guarantee the creation of a truly original or groundbreaking work.

In her book dedicated to the history of literary awards, French scholar Sylvie Ducas explores the evolving dynamics of the contemporary literary scene and the role prizes play within it. She highlights how books often become commodities and marketing tools before they are recognised as creative works.