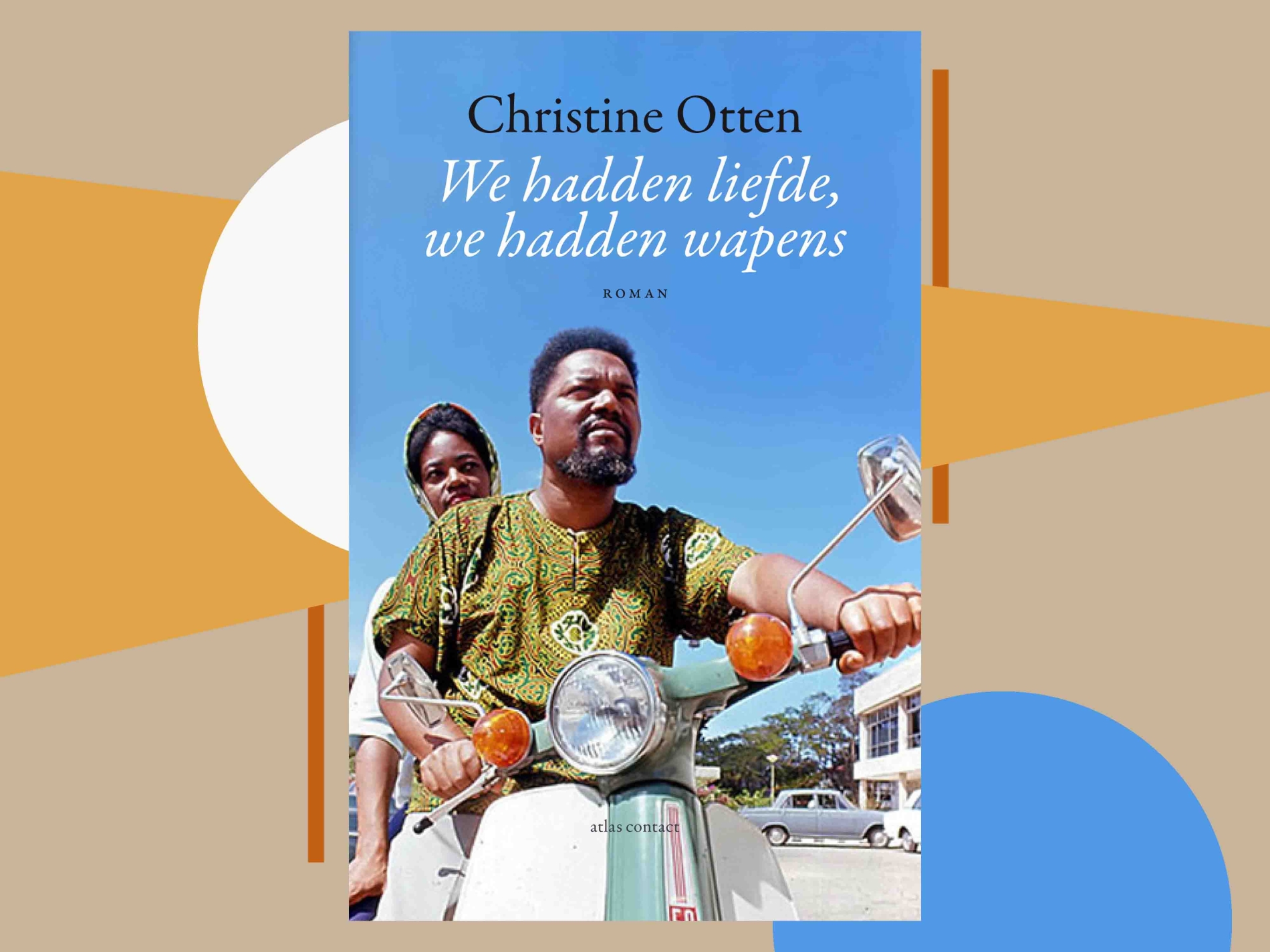

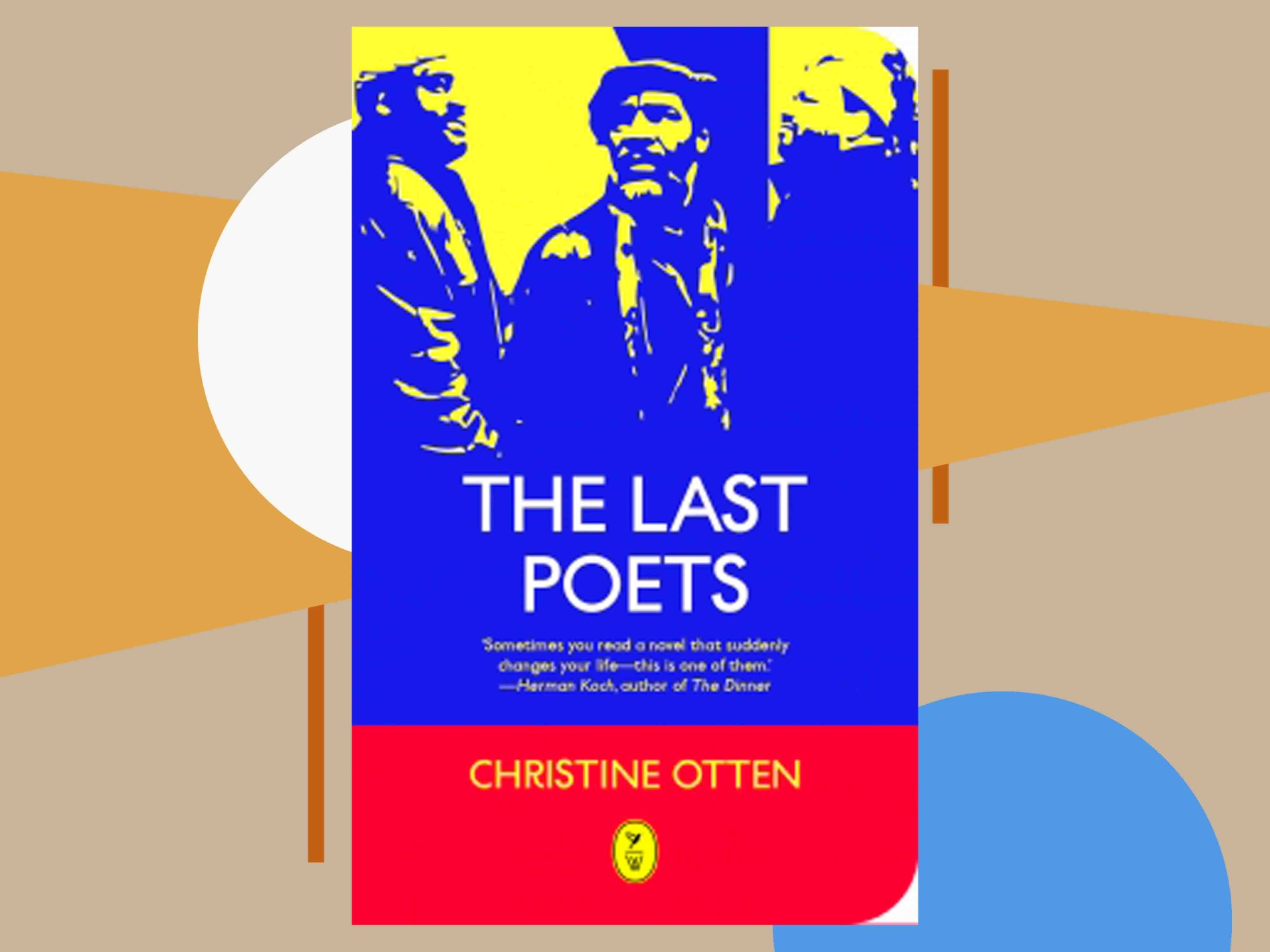

Dutch writer Christine Otten is known for novels and plays inspired by real people. Her breakthrough came with The Last Poets, set in 1969 Harlem in New York, and named after its subjects—a group of African-American artists who helped define popular culture in the United States for the subsequent decades. The novel gained renown for its distinctive rhythmic style and pace when it was published in Dutch in 2004 and subsequently in English.

Her career as a novelist began with 1995’s Blue Metal, about a 15-year-old girl discovering the world of music, establishing the connection through her own work with other art forms. She has also channelled the voices of marginalised groups, including prisoners, and has spoken out over Israel’s war on Gaza. Otten is also a music journalist and is known for performing her work.

She spoke to Al Majalla about the inspiration behind her books and the affinity she has felt with the people whose stories she has told to such acclaim. This is the conversation.

In The Last Poets, you vividly capture the rhythms of the African American spoken word and its ties to the origin of hip-hop. How did immersing yourself in poets' personal archives and live performances shape the novel, and what risks did you take in blending biography with fiction to honour their legacy?

It all started when I first met Umar Bin Hassan and Abiodun Oyewole, two of the original members of The Last Poets, in the Summer of 2000 in New York. It was through my son’s love for hip-hop music that I got to know them, interviewing them for a newspaper. I was not prepared for what happened when we met.

These men were so open and honest about their lives and work. I was immersed in their world and stories that capture 1950s America from an African American perspective.

The stories were about struggle, racism, love, poetry, life, and were very intimate. I clicked with these men, especially with Umar, with whom I had a lot in common. We both had fathers who struggled with psychiatric problems—Umar’s dad because of racism and exclusion, mine because of poverty and estrangement.

We both came from working-class families, and we both knew what it meant to have to be much more mature as a child and the hurt that comes with that.

Of course, Umar had a much harder life than I ever had, but there was a strong personal bond. I guess Umar planted the idea of writing a novel in my head, although I immediately felt compelled to preserve this amazing epic tale.

So, I immersed myself in their history by reading everything I could about the Black liberation struggle, as well as novels by Toni Morrison and James Baldwin. I listened to jazz, soul, and R&B music and watched documentaries.

But most of all, I talked to people, the poets themselves, their wives, ex-wives, daughters, mothers, sisters. A feminine perspective was essential because these men were seen as icons. I wanted to humanise them.

Of course, it's tricky to blend biography and fiction, but the fictional part was mainly getting under the skin of the characters. I followed up on all the amazing stories they told me and got into the characters.

Later, they said I took poetic license, but that it (my depiction) was mainly how it was. I just tried to be honest and write with love and integrity about the poets, without turning them into saints. It helped that they were as open about their flaws as they were about their achievements.

You reconstruct their lives by weaving together fictionalised biography and poetry. How did stepping into the perspectives of Black American men challenge your assumptions about storytelling, and what did you learn about the limits and ethical possibilities of literary empathy?

I discovered I could be anyone. This book was a liberation for me, both as an artist and as a person. But it did not come without pain.

The relationship with Umar and the other poets was sometimes tested because, naturally, there was distrust toward me as a white woman. I felt deeply lonely at times.

I just remained myself and did not pretend to be anything different from who I was. I could connect deeply to their stories and history, and maybe it helped that my ancestors were fighters in a way, working-class people who were very conscious of oppression and fought against it. Eventually, Umar and I had a very close friendship that has lasted till today.

As for the writing, inspired by the group’s own poetic essence—jazz and the ‘wildness’ of their stories—I started writing and discovered for the first time that I could make music with words.