Two-thirds of the way into a trilogy covering the widespread rights abuses of Brazil’s darkest chapter, Henrique Schneider says he wants to highlight what happened because so few of today’s younger Brazilian generation know about it.

A lawyer for Brazilian unions who writes about dictatorship in his limited spare time, Schneider’s first book of the trilogy is set in 1970, when he would have been seven years of age. Although the torture of the government’s political opponents often took place in clandestine prisons, time has revealed what happened.

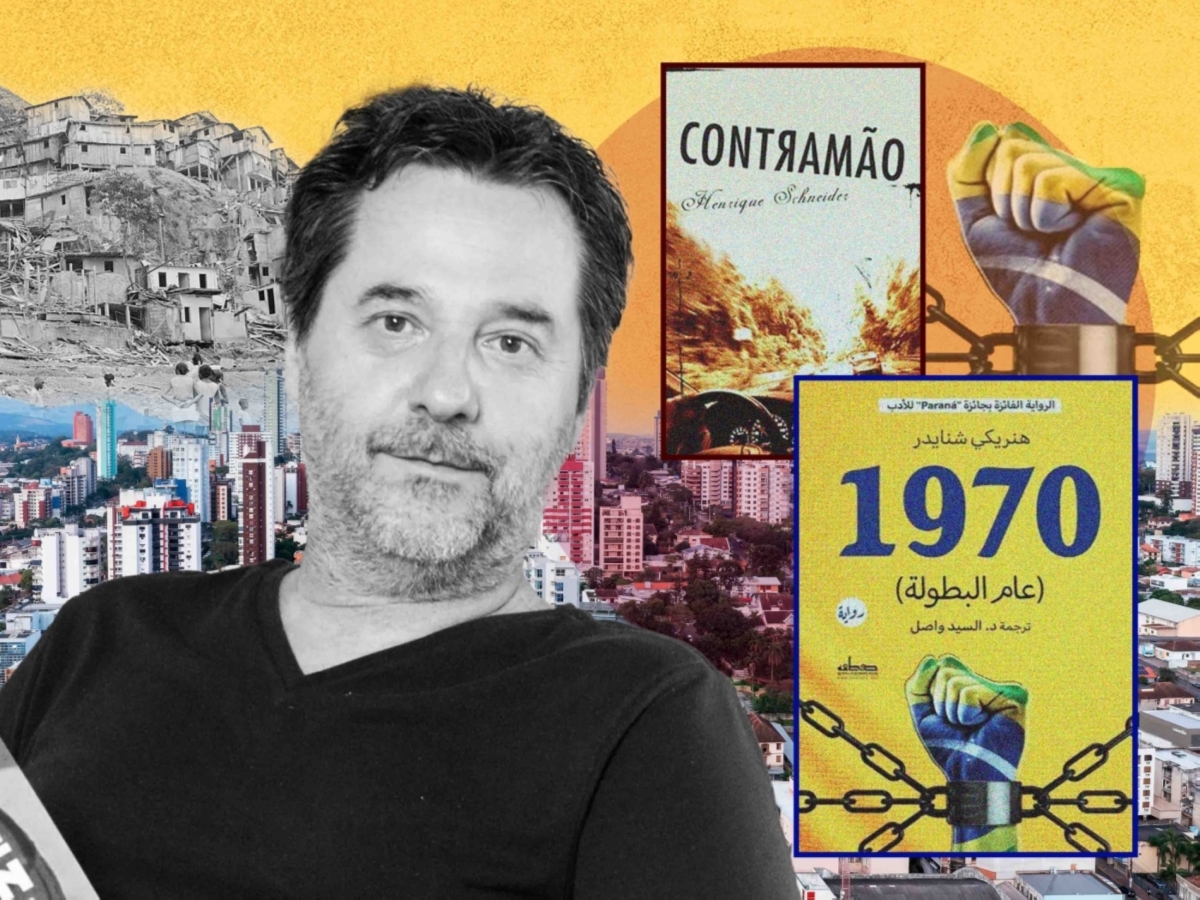

The novels have common themes but can be read alone, says Schneider, the son of a university professor and a congressman who has now won some of Brazil’s top literary awards. He spoke to Al Majalla about life, law, literature, and the danger of history being allowed to repeat itself. This is the conversation.

Your literary works demonstrate an interest in identity, memory, and justice. Was this influenced by your study and practice of law?

I’ve been a lawyer for workers’ unions for more than three decades. It’s a very specific area of law, and it means that, in my work as a lawyer, I’ve always defended the worker’s side, it’s world vision, so it’s not just a profession; it’s a job with commitment. Of course, seeing the world in this way has influenced my writing and still does. It doesn’t mean it has to be an objective influence. It comes naturally.

My lawyer’s life, in a certain way, also lives in my literature, but only as a way of thinking, and of seeing life and world, never as a language—it is too pompous and stilted. The language of literature is far richer and more colourful than the language of the law.

Your novel, 1970, which has been translated into Arabic, is the first novel in your Dictatorship trilogy. Can you share more about this project?

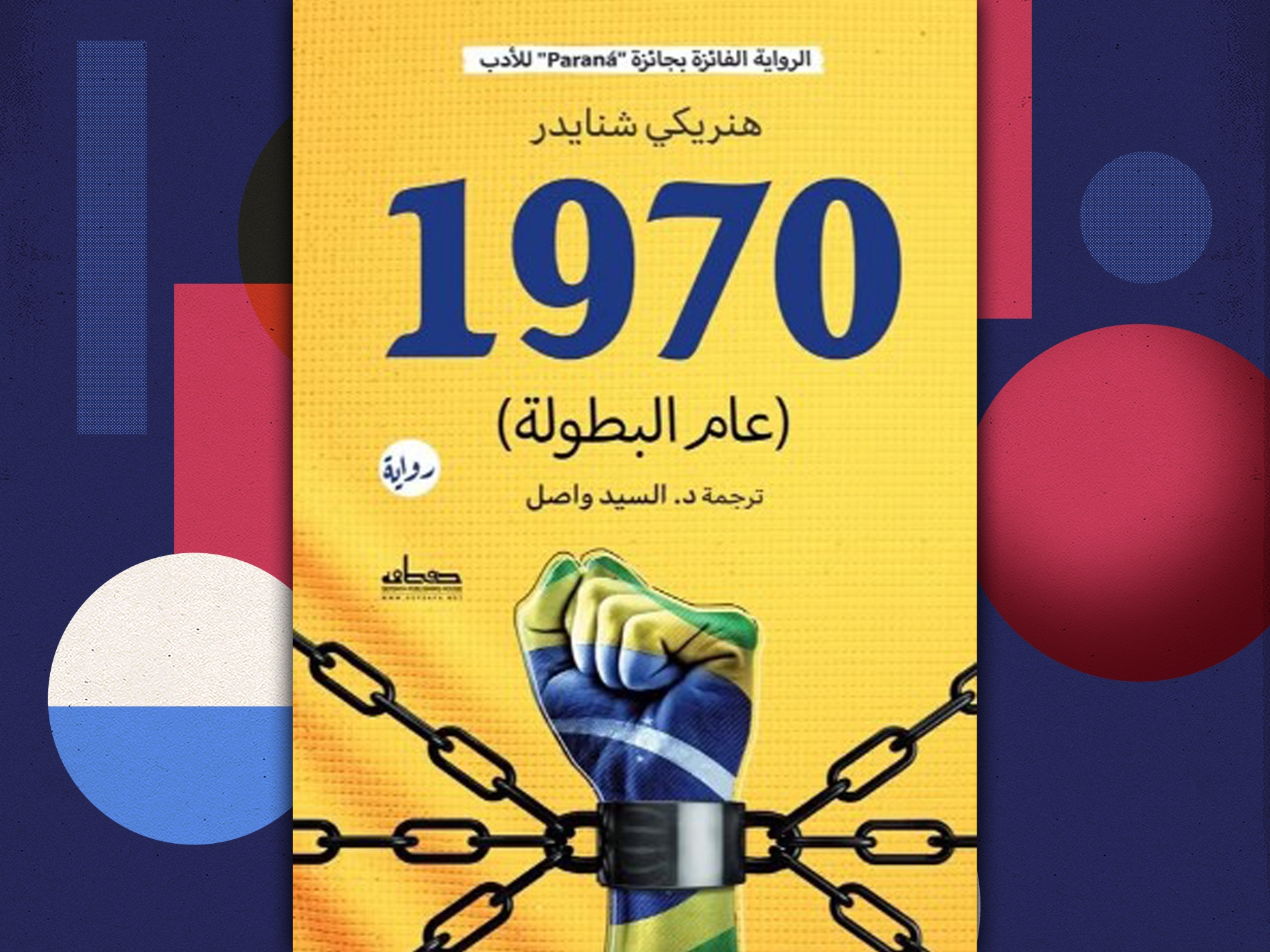

1970 won the Paraná Prize of Literature. It’s published in Egypt, Indonesia and Italy, and its rights are already sold to Türkiye and Colombia. The book’s title refers to a year that was one of the heaviest in terms of repression in Brazil, but was also the year when Brazil won the Football World Cup in Mexico. The book links these two. It is about torture, which was widespread in the Brazilian civil-military dictatorship of 1964 to 1985.

The second book of the trilogy, The Loneliness of Tomorrow, tells the story of a 21-year-old man in his journey to political exile, following threats over his participation in the students’ resistance movement. During this period, the government’s opponents were often pursued, prosecuted, jailed or killed, so many were forced into exile.

The third book, which is about censorship, is still being written. These are three independent novels, but they share some common ingredients: they all happen between 1970-1972, the deepest period of repression; they all have common people as protagonists; and they are all based on real events. I decided to write this trilogy because Brazil discusses this period less than it should. Young people know almost nothing about it. I believe we should talk more, not forget it, and this will help avoid it being repeated.

The novel centres on a young man wrongfully arrested following an assassination attempt on the US ambassador to Brazil. It portrays his mother’s desperate search for him and depicts scenes of torture as authorities try to extract a confession. How were you able to write these intense scenes, and are they based on real events?

All three novels are based on real facts. My writer’s hand just fictionalised it a little. There was torture during this period, torture classes in clandestine prisons, and a plan to kidnap the US consul in my state—it failed. So, everything in the book happened. I just had to put it all together and write.

You asked about the mother's desperate search for her son. In this novel, the mother also symbolises the evil effects of dictatorship and repression of normal people who were not involved in politics and who may even have felt alienated about what was happening in the country at this time.