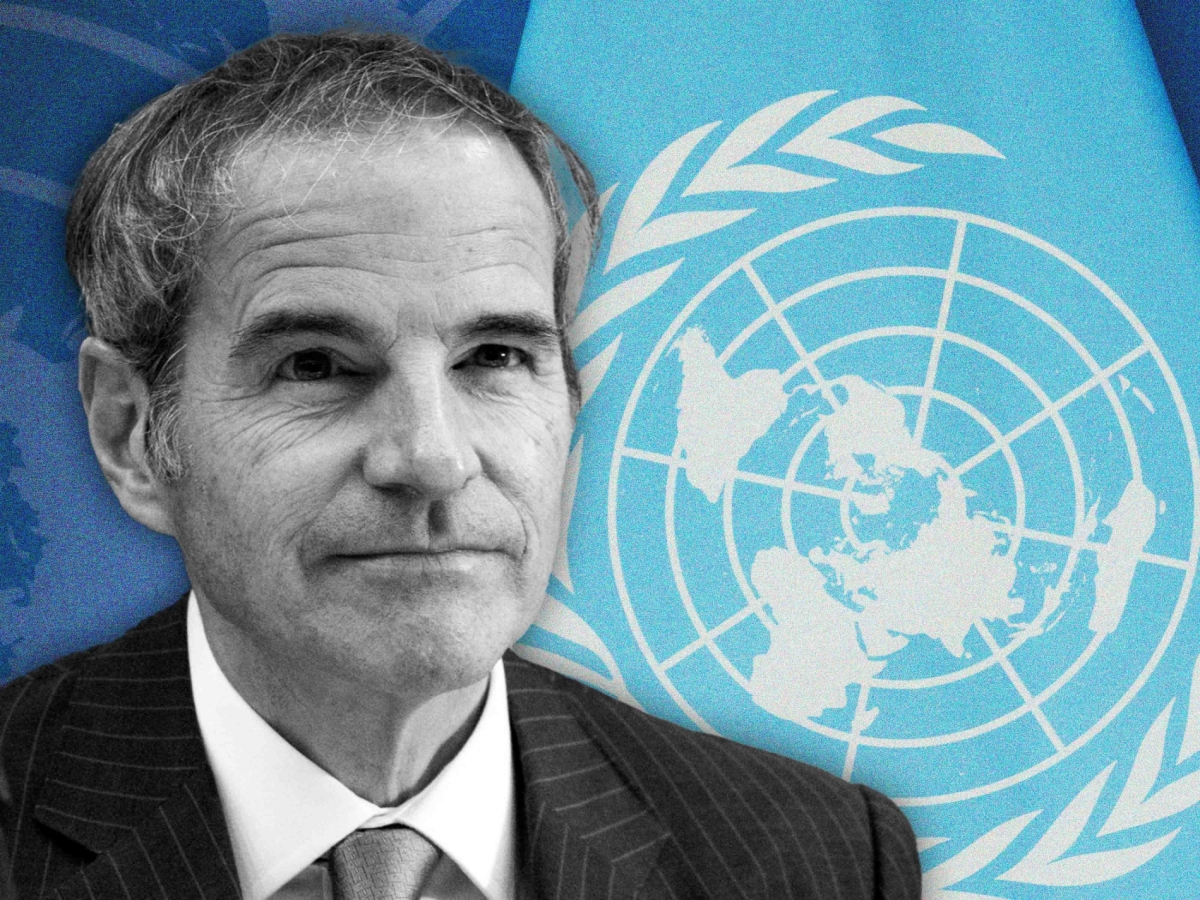

During a recent visit to Washington, the Director General of the International Atomic Energy Agency IAEA) Rafael Grossi said he intends to run for the position of UN secretary-general. The announcement came after months of intense speculation, especially in his native Argentina, that he was planning to make a bid for the position.

“The wheel has begun to spin,” said Grossi, explaining that the process to finalise his candidacy would be set in motion “in the coming weeks.”

Grossi had already flirted with the notion of running during a recent visit to Buenos Aires in April, although at the time he insisted that no final decision had been taken.

The position of UN secretary-general is due to become vacant in January 2027, when Portuguese diplomat António Guterres’ term in office ends. Election leads to a five-year term, with the possibility for re-election.

If successful, Grossi, who is married and has eight children, would become the second Latin American to hold the post after Peru’s Javier Pérez de Cuéllar.

The unwritten tradition at the UN is that the position of secretary-general rotates between geographical regions. As the two previous appointments have been awarded to European candidates, there is a strong feeling at the UN headquarters in New York that the next appointment should be drawn from the Ibero-American bloc. Given the influence of the United States at the UN, Washington is not expected to put up a candidate.

Timely and important exchange with @StateDept’s @SecRubio @marcorubio today in Washington, D.C. on @IAEAorg’s work in Iran & Ukraine and strong US–IAEA cooperation as nuclear innovation advances.

Grateful forcontinued support to our mission for peace. pic.twitter.com/J0NzRwRnk5

— Rafael Mariano Grossi (@rafaelmgrossi) August 27, 2025

During his press conference, Grossi revealed that he brokered the subject of his nomination at a meeting held with US Secretary of State Marco Rubio, although there has been no indication that the Trump administration is preparing to lend its backing to Grossi.

Early life and career

Born in Argentina in 1961, Grossi graduated from the Pontifical Catholic University of Argentina in 1983 with a BA in Political Science before joining the Argentine foreign service in 1985. During his long service in the Argentine diplomatic corps, he also pursued an MA and PhD in History, International Relations, and International Politics, graduating from the University of Geneva and the Graduate Institute of International Studies in 1997. In addition to Spanish, his mother tongue, Grossi is fluent in French and conversational English, Dutch, and German.

Although he has held ambassadorial roles, including being appointed Argentina's ambassador to Austria in 2013, much of his career has been spent focusing on nuclear non-proliferation and issues related to weapons of mass destruction.

Before his election as the IAEA’s Director General, Grossi was president-designate of the 2020 Review Conference of the Parties to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT), and from 2014 to 2016 served as president of the Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG). He was the NSG’s first president to serve two successive terms.

After serving as ambassador to Austria, he became the Argentine Representative to the IAEA and other Vienna-based International organisations. From 2010 to 2013, he served as Assistant Director General for Policy and Chief of Cabinet at the IAEA.

Prior to working with the IAEA, Grossi was Chief of Cabinet at the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) in The Hague from 2002 to 2007. Prior to this, he served in the Argentinian Foreign Ministry, including as Head of Embassy in Belgium and Luxembourg from 1998 to 2002, and as Argentine Representative to NATO from 1998 to 2001.