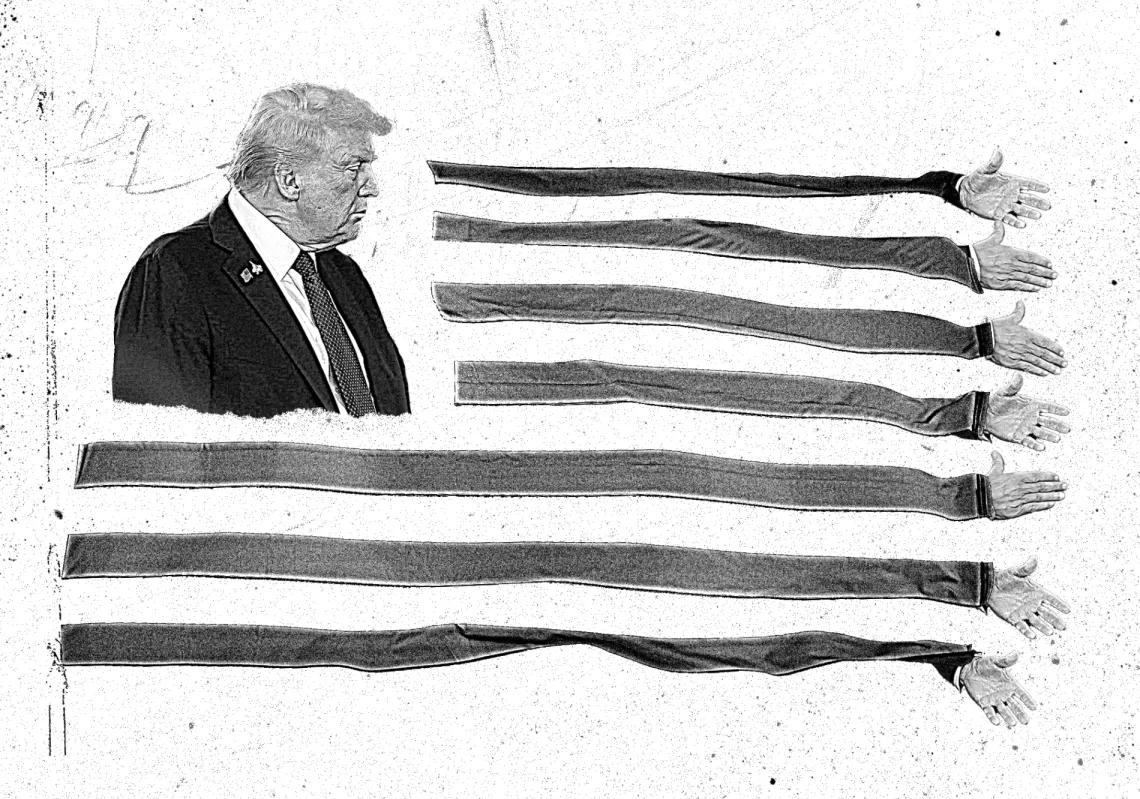

With a hesitant United Nations endorsement, the proposed Board of Peace was initially devised to uphold the ceasefire in Gaza, oversee reconstruction, and foster stability. In recent weeks, however, it has moved away from the limited mechanism originally put forward. Today, its primary purpose seems to be promoting US President Donald Trump’s agenda and projecting his personal dominance.

Forced through under significant pressure from Trump, the charter now mirrors the structure of the UN but affords him a personal veto over any resolution he opposes. Acting under the authority claimed by this document, he has secured his own leadership of the Board and offered permanent membership to anyone who pays $1bn.

The Board of Peace is the ultimate oversight body for Gaza. There are two other groups that it is designed to oversee. The first is the Palestinian National Committee for the Administration of Gaza (NCAG), which was assembled on 14 January, but whose 15 members have not yet been allowed into Gaza by Israel. The NCAG has been described as “technocratic” and will administer Gaza, but won't have the trappings of a typical government. The other is the executive board, which is mainly comprised of businesspeople.

Getting onboard

In a joint statement, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and Türkiye signalled their interest in joining the Board of Peace, alongside Israel, Jordan, Indonesia, Pakistan, and Qatar. They were later joined by Albania, Bahrain, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Hungary, Kazakhstan, Morocco, and Vietnam. At the time of writing, 19 countries had joined the United States on the Board, including Jordan, Saudi Arabia, Pakistan, Qatar, the United Arab Emirates, Morocco, Bahrain, and Türkiye.

In total, Trump has invited 60 countries. Many have expressed reservations, including several major European states. In private, they wonder what the Board’s real purpose is. Slovenia’s Prime Minister Robert Golob said the Board represents a serious encroachment on the broader international system. Although established in response to the conflict in Gaza, its founding charter makes no mention of the territory. Large portions of the Board’s remit duplicate the responsibilities of international bodies.

Saudi Arabia acknowledged that the original goal had been approved by the Security Council and expressed support for the charter’s stated commitment to a just and lasting peace in Gaza. This implicitly signals discomfort with the Board’s expansion into a quasi-global institution with authority to intervene in other conflicts. Russia, China, the UK, France, and even the Vatican have given hesitant or conditional answers. Israel is also reluctant.