In modern international diplomacy, few developments carry more weight than the quiet withdrawal of a superpower, which is unfolding as the United States exits 66 international organisations—31 United Nations entities and 35 other global bodies. Washington is doing far more than reducing its membership roster. It is dismantling key pillars of the post-World War II international architecture that it helped design, legitimise, and sustain.

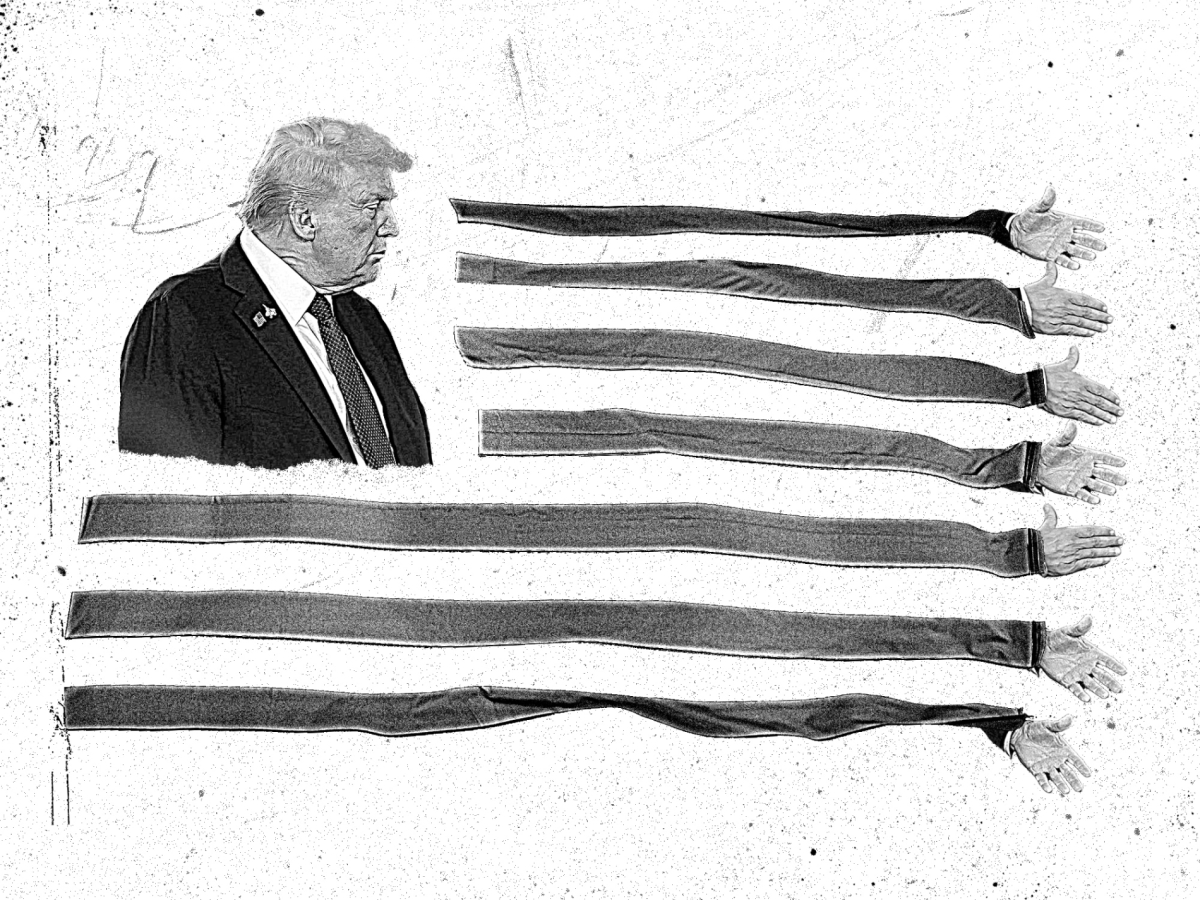

The ‘America First’ doctrine pushed by US President Donald Trump takes aim at multilateral institutions working on climate change, trade, development, and international law, to name but some. Yet this is no sudden rupture. Rather, it is the acceleration of a longer-term trajectory long spotted by observers: the gradual erosion of a unipolar order centred on American leadership, and the emergence of a multipolar world increasingly organised around regional spheres of influence.

As destabilising as this moment appears to proponents of multilateralism, it may paradoxically present the global community with the reason to undertake meaningful reform of an international system whose dysfunction and paralysis have become increasingly unsustainable. Does the rest of the world have the political will to seize the moment? Or will the US withdrawal simply hasten the system’s descent into irrelevance?

Rejecting internationalism

The intellectual foundation for America’s policy shift is explicitly laid out in the recently released 2025 US National Security Strategy. Withdrawing from international organisations is the deliberate execution of a coherent—if controversial—doctrine. The strategy rejects broad, values-driven internationalism in favour of a narrowly defined national interest calculus.

It declares that “the days of... propping up the entire world order like Atlas are over”. It privileges sovereignty, economic strength, and regional dominance over maintaining a liberal international order. In practice, this translates into transactional bilateralism and a deep scepticism toward international legal and institutional constraints.

Where previous national security strategies framed global institutions as indispensable platforms for collective problem-solving, the 2025 NSS sees them as diluting or undermining US influence. Trump calls organisations like the UN Population Fund, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), and the International Union for Conservation of Nature “globalist bureaucracies” misaligned with American priorities.

The immediate crisis confronting the UN system is both existential and financial. In the past, the US contributed more than a fifth of the regular UN budget, and more than a quarter of its peacekeeping, yet Trump now proposes cutting funding for most UN bodies, even withholding funds already authorised under previous Congressional appropriations.

For his part, UN Secretary-General António Guterres said assessed contributions constitute “a legal obligation under the UN Charter,” but ‘legal obligations' carry limited weight when the violator is the world’s largest economy.

The consequences extend to voluntary contributions, which fund the bulk of UN operational activities—from climate mitigation initiatives (such as UN-REDD) to education in emergencies to programmes combating sexual violence in conflict. Withdrawing funds will cause immediate harm to vulnerable populations worldwide.