Reappraisal of CAIR

The transformations of the post-2011 era and the subsequent regional chaos pushed the US security establishment to reconsider its diagnosis. It has moved closer to Arab allies' views: that unity of origin implies unity of destiny; that the separation between the proselytising (da'wah), political, and jihadist arms is procedural rather than substantive; and that the Brotherhood constitutes a single, genetically interconnected network.

Thus, the scene cannot be reduced to a crisis of CAIR alone. The current movement continues a legal path that began with the Holy Land Foundation trial in 2007, which situated the organisation within the Brotherhood network and branded it an 'unindicted co-conspirator'. This shift, which drove the FBI to sever official relations with CAIR, coincided with deep revisions within the American Muslim fabric itself.

Leaks about the 1993 Philadelphia meeting—where security recordings documented discussions among founders to establish a civil umbrella that provided political cover for the movement—reinforced the conviction that CAIR was created as a factional front rather than an inclusive umbrella.

This helps explain accusations that CAIR systematically tips the scales in favour of 'movement' political Islam while marginalising independent Arab and Muslim forces. The matter extends to involvement in regional agendas, capped by the UAE designating the organisation as a terrorist group in 2014, cementing its image as an active party in political disputes between Arab governments rather than purely a human-rights defender.

The intersection of American and Arab security visions gave the anti-political-Islam narrative normative power in Washington and paved the way for measures now unfolding in Texas and beyond.

Texas and Florida model

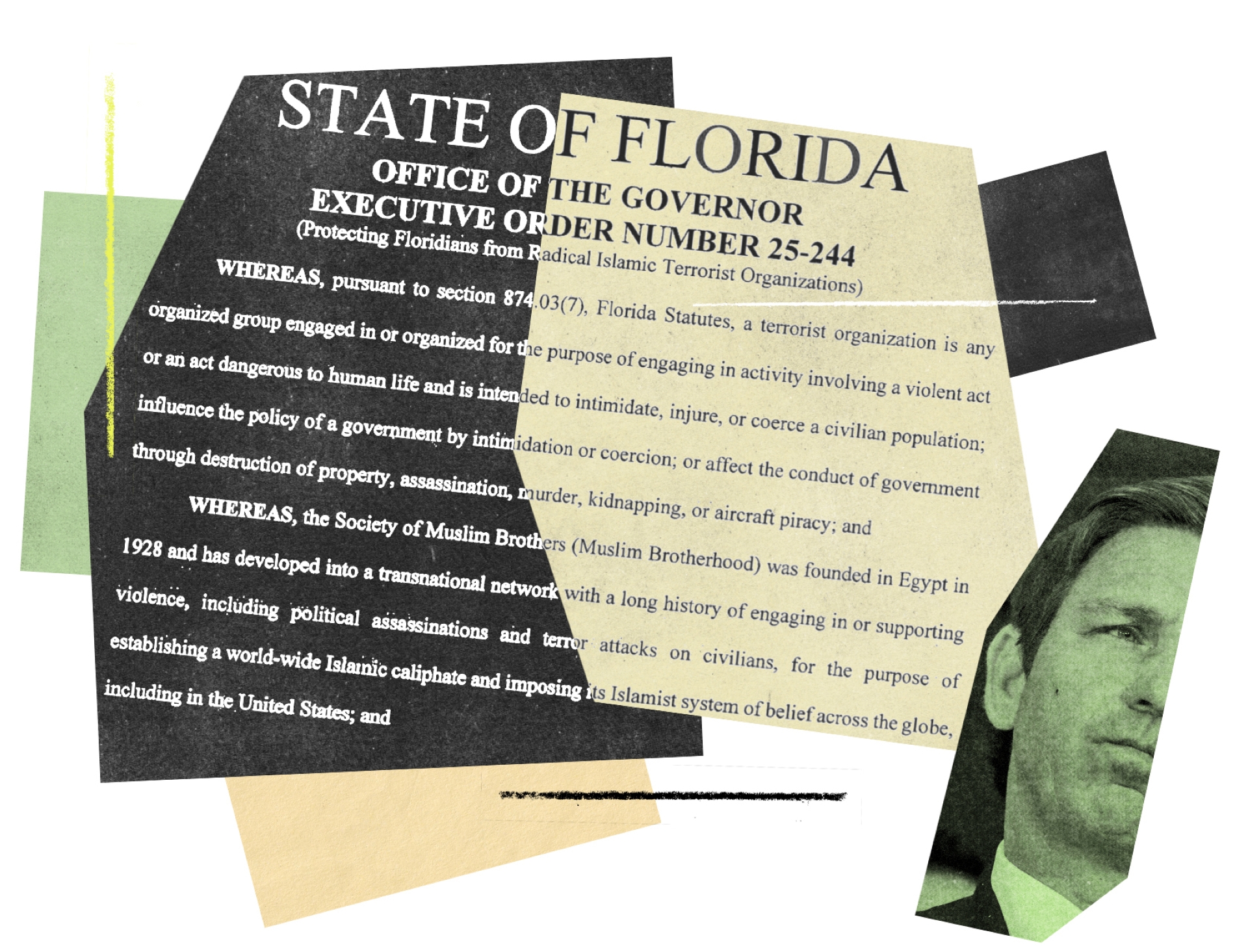

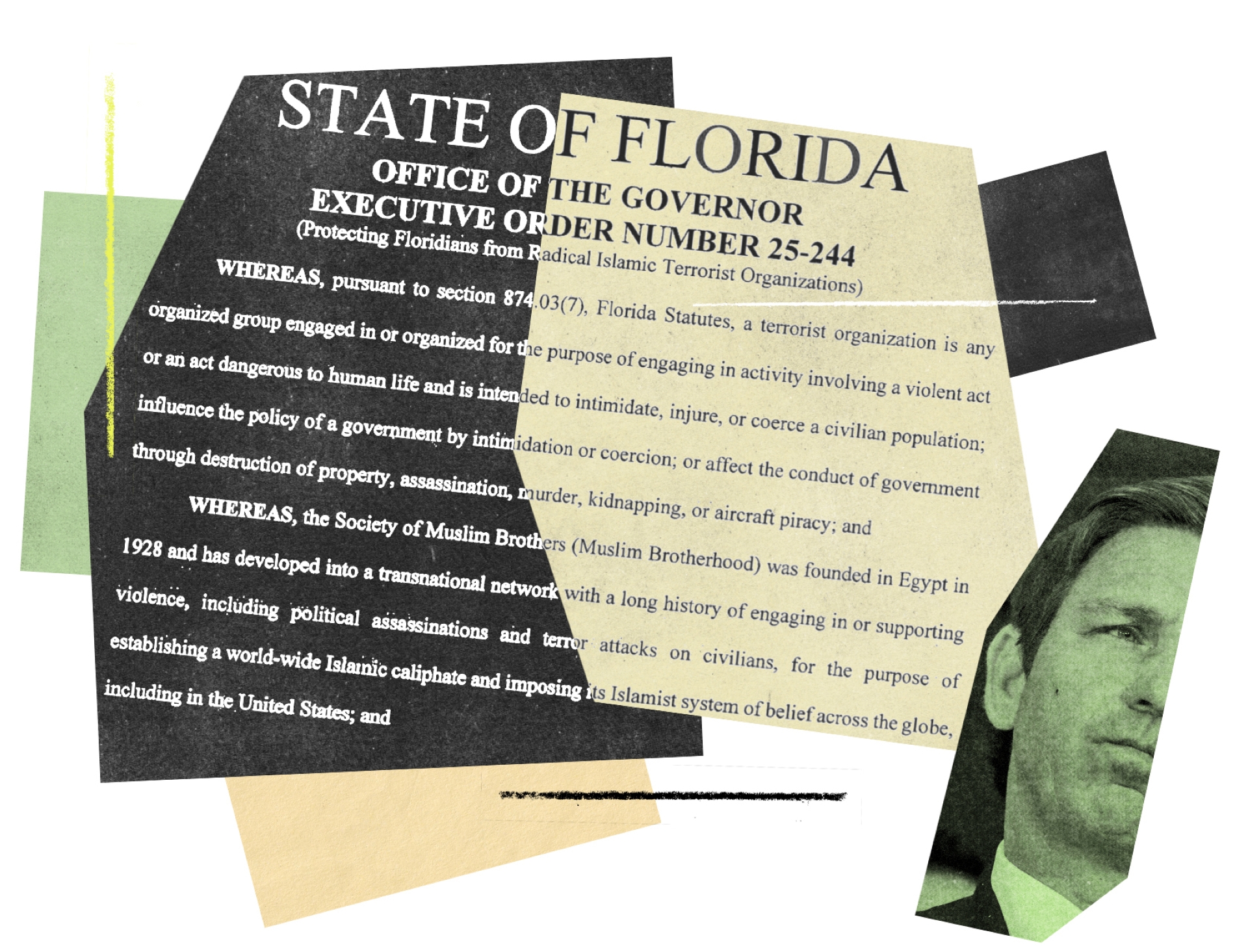

On 18 November, these theoretical convictions crystallised into legal reality. Texas Governor Greg Abbott issued an executive order designating CAIR and the Muslim Brotherhood as foreign terrorist organisations. Less than a month later, on 8 December, Florida Governor Ron DeSantis issued Executive Order No. 24-244, employing the same classification: foreign terrorist organisation.

This synchronisation reveals high-level Republican coordination to transform 'red states' into a hostile environment for these entities. A careful sociological and legal reading exposes dangerous implications that redefine institutional citizenship. The first implication is the stripping of the national cover. Applying the term 'foreign' to an organisation of American origin, registered since 1994, delegitimises its national status.

The authorities decide that presumed ideological loyalty to the Muslim Brotherhood overrides legal status as an American institution, inaugurating a systematic process of 'othering' that transforms the institutional citizen into an alien intruder and facilitates targeting without the usual constitutional restraints.

The second, more dangerous implication is spatial exclusion. The orders prohibit these entities from purchasing or owning land, thereby denying them the spatial conditions necessary for their existence in the language of urban sociology. In Florida, the siege takes an even fiercer bureaucratic turn. The executive order explicitly deprives individuals or institutions that provide material support of privileges or resources and directs government agencies to terminate contracts, preventing the material localisation of the group and making its physical existence nearly impossible.

Here, Weber's iron cage transforms from a metaphor into solid legal walls preventing the group from breathing spatially and financially. Authorities are not content with stripping ideological enchantment; they strip physical space, turning the cage into a tool of material isolation. In practice, this may extend to freezing bank accounts under 'risk management' clauses and terminating lease contracts, producing operational paralysis that forces the organisation to deplete resources in logistical battles for survival rather than its human-rights mission. It is a literal application of bureaucratic strangulation.

Added to this are directives to investigate alleged Sharia courts, opening the door to comprehensive security surveillance. Every religious gathering or family arbitration becomes a subject of suspicion, creating an environment of moral panic.

Function vs essence

The central paradox lies in CAIR's defence strategy. While the state brands it as terrorist based on its essence and historical roots, CAIR invokes the language of numbers to prove the legitimacy of its function as a civil-rights defender. Recent data from the organisation reveals a statistical explosion in grievances: in 2024, CAIR recorded 8,658 civil-rights complaints nationwide, a 7.4% increase over the previous year. The inflection point came with the events of October 7; in the two months following the war's outbreak, complaints jumped by 172% compared with the same period a year earlier.

Behind these numbers are human stories: a university student in Austin threatened with expulsion for wearing a keffiyeh, or a veiled employee facing arbitrary dismissal. In such cases, CAIR intervened less as a 'political group' than as a community law firm. This functional role makes dismantling it tantamount to amputating the only safety net thousands of American Muslims rely on, turning the organisation into an indispensable legal 'oxygen tube'.

CAIR employs these figures to argue that an entity addressing thousands of discrimination cases cannot rationally be classified as a terrorist organisation. The data also suggests a qualitative shift: employment discrimination cases topped the list, exceeding 15%, while complaints related to law enforcement jumped by over 70%, reflecting intense tensions in universities and public institutions.

What emerges is a structural conflict. The organisation defends its function as a necessary rights shield, while the state attacks its essence. It is a living embodiment of the Weberian iron cage—a clash between the logic of the 'mission' (daily services) and the logic of the 'cage' (rigid security classifications). The iron cage does not care about humanitarian services, only about the discipline of the security machine; the state's success in striking the essence will automatically collapse the function, leaving thousands without legal cover.

Globalising security standards

Events in Texas, Florida, and Washington, D.C., must be read within a broader geopolitical context. The US is joining a wave of 'globalisation of security standards' in dealing with political Islam, a wave that began in Europe. What Abbott and DeSantis are doing, and what Republicans in Congress aspire to, is an American version of Austria's Documentation Centre for Political Islam and France's 2021 Separatism Law.

In both European cases, the methodology was identical: a shift from criminal prosecution of individuals (requiring proof of material crime) to administrative strangulation of institutions (requiring only proof of ideological suspicion). Associations in Austria were dissolved based on intellectual orientations; in France, imams were asked to sign loyalty charters.

The lesson is profound. Targeted organisations did not disappear; they became ghost entities, legally present but functionally paralysed and politically silent. CAIR may be pushed toward similar tactics of survival, including restructuring or rebranding to escape a 'tainted reputation', beginning a prolonged game of institutional cat and mouse.

This similarity reflects security cross-pollination between the Western right and Middle Eastern security approaches, where danger is defined not by who carries a weapon, but by who carries a project parallel to the state.

Accelerator and trap

Gaza appears as a decisive accelerating factor. The surge in complaints in American universities cannot be separated from the war; Gaza has become both the generator of these grievances and the trap used to demonstrate CAIR's foreign loyalty.

When CAIR demands a halt to arms exports, it does so in response to pressure from its angry grassroots base. Internally, this was not a luxury; the leadership faced a clear threat of abandonment if it remained silent. CAIR thus found itself torn between maintaining traditional lines with the White House and adopting the anger of the street, choosing the latter and betting that popular legitimacy is its last fortress.

Yet, under the new security doctrine, such deep engagement in foreign policy is read as definitive proof that the organisation is a political actor with transboundary loyalties. Every complaint about freedom of speech for Palestine becomes potential evidence of radicalism. Statistics meant to serve as a protective shield are recast as indicators of guilt in the eyes of the American right.

Congress and the 'original sin'

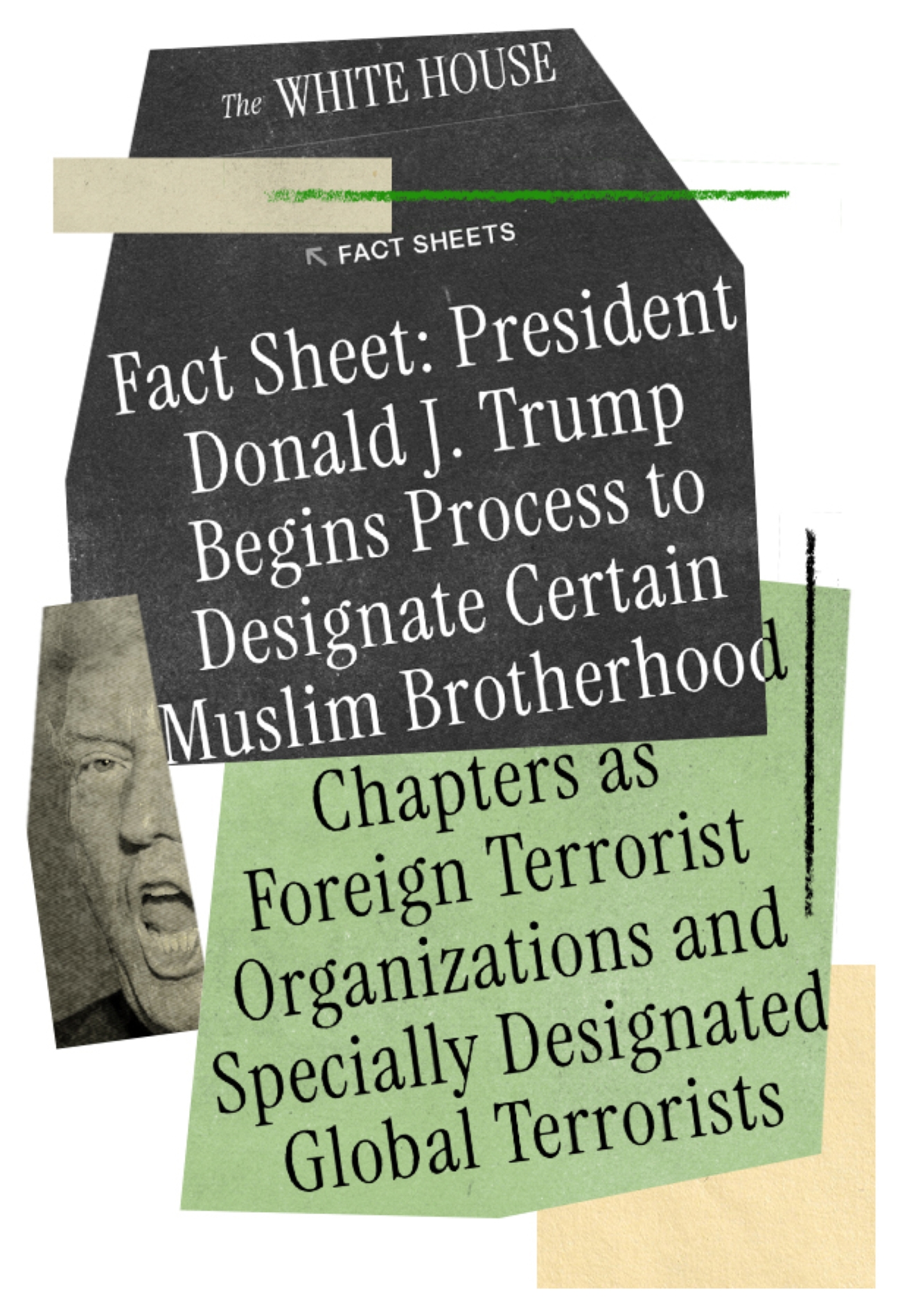

But as lawyers managed discrimination cases, a legislative pincer movement was underway in the 119th Congress (2025-26). H.R. 4097 was legislation that directed the Secretary of State to investigate CAIR's eligibility for terrorist designation. Second, and more severe, H.R. 4397 obligated the president to designate the Muslim Brotherhood as a foreign terrorist organisation, which is what happened on 13 January. The House Foreign Affairs Committee debated these files in December 2025, moving the issue from theoretical expectation to direct legislative decision.

The danger lies in the investigative methodology. It leaps over the organisation's recent record and returns to the archives of 2007, deciding that the statute of limitations does not apply to ideological affiliation. The process relies heavily on Holy Land Foundation trial documents that classified CAIR as an unindicted co-conspirator—a label used procedurally to admit hearsay evidence, without the organisation being afforded a chance to defend itself. This 'procedural stigma' has been transformed in right-wing narratives into a permanent 'life sentence', summoned retroactively to destroy three decades of institutional work.

Neither CAIR's record numbers in serving the community nor the fact that its foreign funding does not exceed 1% seems to intercede for it. What matters to the new security mindset is organisational DNA and founding funding. This trend toward historical excavation aligns with the methodology of Arab security states: the criterion is intellectual roots, not current slogans. The goal is to tighten the iron cage, using cold bureaucracy to suffocate the organisation; the state does not confront the idea with a counter-idea, but crushes it under procedure.

The blow targets not only CAIR but also its donors. Once the organisation comes under federal scrutiny, supporters withdraw, resulting in a self-inflicted drying up of resources.

After CAIR: liquid radicalisation

The pressing question in Washington is no longer how to close such organisations, but what happens after. Socially, entities such as CAIR serve as intermediary institutions that channel societal anger into legal and constitutional channels. Dismantling them may lead to 'liquid radicalisation': grievances persist, but the organised frameworks capable of disciplining them disappear.

When the institution closes, the grievance does not evaporate. The mass loses its organisational compass and may drift toward underground work or undisciplined individual extremism. Replicating the Arab model of 'drying up sources' may eliminate bureaucratic structures, but in the open American context, it creates a functional void the state cannot easily fill. That void leaves the arena open to narratives that reject human-rights work or the constitutional order, while community members view authorities as preventing them from exercising civil rights.

This brings the discussion back to Weber's iron cage, in which the state attempts to rationalise institutions in the name of security, only to strip citizens of civil rights without sufficient legal evidence. What CAIR faces today goes beyond a 'new McCarthyism'. It is a historical moment in which exceptions fall, and security standards are globalised, the shadows of the East penetrate the American firewall, and the distinction between 'terrorist' in the Middle East and 'civil' in the West collapses.

The organisation now faces a fate resembling bureaucratic death. The battle is no longer about protecting rights but about defining the enemy. The definition that views the Muslim Brotherhood as an existential threat has become the adopted standard in the new US.