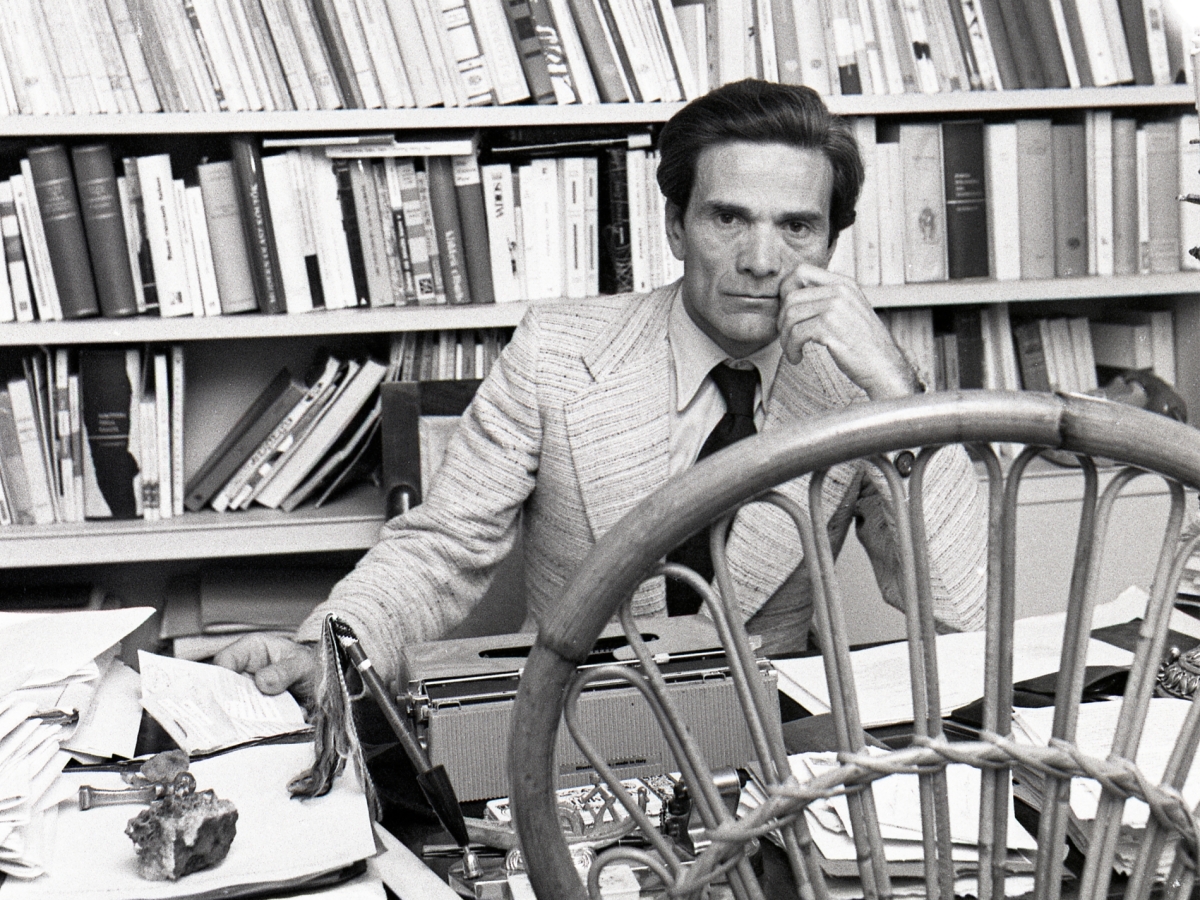

On the cover of the first edition of his final poetry collection, Trasumanar e organizzar, the Italian poet and filmmaker Pier Paolo Pasolini included a foreword that begins with the following statement: “The true readers of this book are those capable of attributing to it a certain objectivity.

Admittedly, this applies to all poetry books in Italy, but it is especially necessary in this case because, at least in its first half, the book is composed of ‘documents’—either private (bearing witness to a life), or literary (bearing witness to linguistic and intellectual development).”

Could it be this deliberately ‘non-poetic’ aspect of the collection that explains why it remained beyond the reach of poetry translators for so long? The question is not posed to excuse an indefensible neglect, but rather to understand why it has taken over half a century, and the resolve of translator Florence Pazotto, for the work to become accessible in French.

Her translation arrives at a fitting moment, not only because it addresses a long-standing and unjust oversight, but also because its recent release in Paris by Éditions LansKine coincides precisely with the 50th anniversary of Pasolini’s murder, which, to this day, remains cloaked in mystery.

Italian poet, Marxist and openly gay Pasolini loved this neighborhood. Necci @Necci1924 was a bar which was expanded to a little haven. There he loved to write. #migration #Research pic.twitter.com/IoVLB0F2WA

— profhuq/সম্তলৗ হক (@profhuq) July 3, 2023

Cantos of Purgatory

Trasumanar e organizzar is divided into two main parts, each comprising several sections, and contains 63 poems written by Pasolini between 1968 and 1970, most of which were originally published in various literary journals. These are relatively long poems, with many addressing key events of the time and public figures, while others focus on central figures in the poet’s personal life, such as Ninetto Davoli, his longtime companion, or the singer Maria Callas, who took on the only acting role of her career in his film Medea, and with whom he shared an intimate relationship that bordered on love.

Pazotto notes that Pasolini initially considered naming the collection after one of its poems, The First Six Cantos of Purgatory, with the addition and Other Communist Poems, before ultimately settling on Trasumanar e organizzar. Of this title, he once explained: “‘Trasumanar’ is used in the mystical sense of an asceticism that defies description—unspeakable, because it is a meta-historical experience. I pair it, with ironic parody and phonetic play, with ‘organizzar’, which is its antithesis, because it refers to worldly, pragmatic action, and can also suggest party organisation, undeniably of a revolutionary kind.”

Pazotto also notes that ‘trasumanar’ derives from Dante, who used the word only once, in the opening canto of Paradiso, while ‘organizzar’ is taken from Antonio Gramsc

Dante’s presence is strongly felt throughout the collection, especially through The Divine Comedy, most clearly in The First Six Cantos of Purgatory, Project of a Poem, as well as in numerous direct and indirect quotations and the recurring themes of the father and the guide. Gramsci, by contrast, is never mentioned by name. Yet several poems speak directly to the Italian Communist Party, which the poet once joined but was later expelled from due to his libertine lifestyle.