Apart from a single line on Wikipedia, there is no information available in Arabic about the Norwegian poet Gunvor Höfmo (1921-1995), despite her being one of the most prominent voices in modern Norwegian poetry. Yet even outside the Arab world, she can be little understood. French poet and writer André Breton, who co-founded surrealism, called Höfmo the “unknown superior”.

As such, the 30th anniversary of her death may be cause to once again bring her words to a wider audience. Most will be familiar with The Scream, a painting by her compatriot, Edvard Munch, which encapsulates Höfmo’s tragic life and its dark, tormented chapters, including one 16-year spell in an asylum.

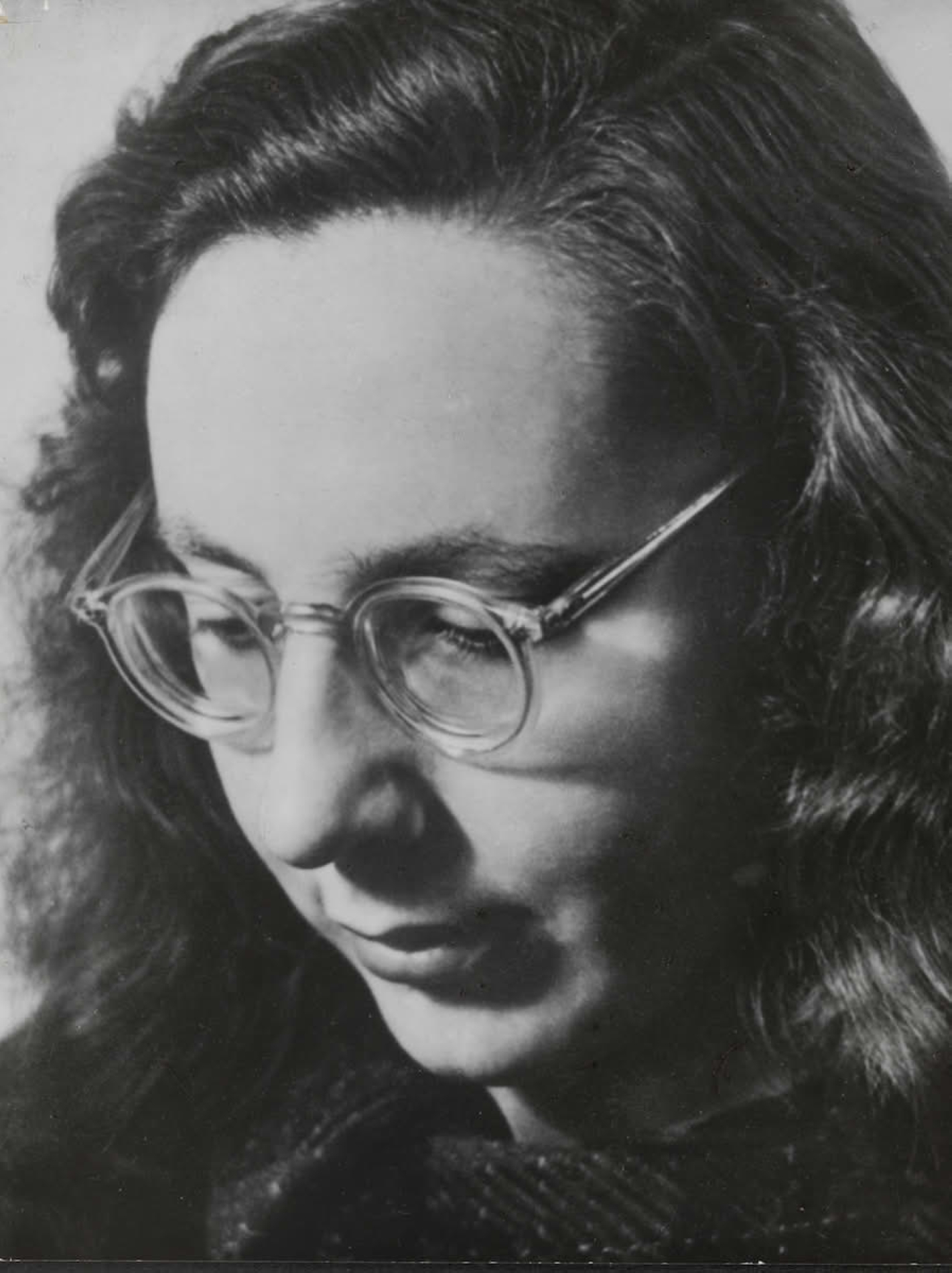

Gunvor Höfmo had a unique poetic vision and is now regarded as something of a priestess or icon within the temple of modern poetry. She grew up in a working-class family in Oslo, surrounded by socialists and communists, and sent her first poems to newspapers and magazines. Among them is one dedicated to her then-close friend Ruth Maier, who was killed in Auschwitz at the age of 22.

It begins:

The words, shining silent, I shall find; Give them to you; Hammer some moments together; Under the frame of eternity; So you will never forget me

The murder of Maier became a central tragedy in Höfmo’s life, and from 1943, she was confined in an asylum at the start of a long, painful struggle with depression that she never fully overcame. After a brief period of travelling across Europe, she published brilliant critical essays inspired by her journeys and Scandinavian poetry, before publishing five collections of poetry between 1946 and 1955.

Torment and rage

Unfortunately, in 1956, illness struck again, and she was once more confined to an asylum, where she remained until 1971, diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia. As she later recalled, it resulted in “16 years of silence”. Following her discharge, she produced 15 more collections of poetry between 1971 and 1994, but from 1977 until her death, Höfmo lived in complete isolation in her Oslo apartment.

The main sources of inspiration for Höfmo’s poetry are the torments of war she witnessed as a child, the guilt of having survived while her friend Ruth did not, and a profound rage. Her style is minimalist and precise, her prose taut as a rababa string. The writing stuns with its sincerity and metaphysical unity, never leaving the intimate but rising with a whispering, majestic voice that emerges from the darkness.

About Ruth, who was arrested in Oslo, she wrote:

I saw my friend, my only friend, I saw her going to death; And since then, the trees are in mourning; Since then, death has dragged my body, my soul, my voice; To the depths of the ocean of despair

Her poems are like faint lights shining in the dark. Critics compared her to the likes of George Trakl, Nelly Sachs, and Paul Celan. She once said: “The best poem is the one we don’t want to write, because it’s too expensive.” From her first collection, I Want to go Home to the Humans, Höfmo wrote

I want to go home to the humans; Like a blind man is transilluminated in the dark; By sorrow´s starlight

This poem immediately reveals the source of her creativity:

I thought am on the other side; Where grass blades are chiming bells of grief and bitter expectation; I’m holding someone by the hand; Looking hard into somebody’s eyes; But I am on the other side; Where each person’s a mist of loneliness and fear

In this unique, almost biblical project, Höfmo’s overflowing confidence in the power of words shines. In a life consumed by loneliness, her words became her closest companions. Through them, with them, and within them, she laid herself bare across 20 collections and nearly 700 poems, constructing an entire world with a singular perspective on it.

Witness to destruction

Today, she is marked by her immutable identity and unwavering longing for the eternal. Her words are firmly rooted in her time—an era of desolation and destruction—yet also stand apart from it. Her world was a world emptied of humanity, something she reflected in her collections Blind Nightingales (1951) and A Will to an Eternity (1955). It was as if the darkness of the world underscored the need for poetry, which, in its own way, yearns to rebuild what war shattered in the human spirit.