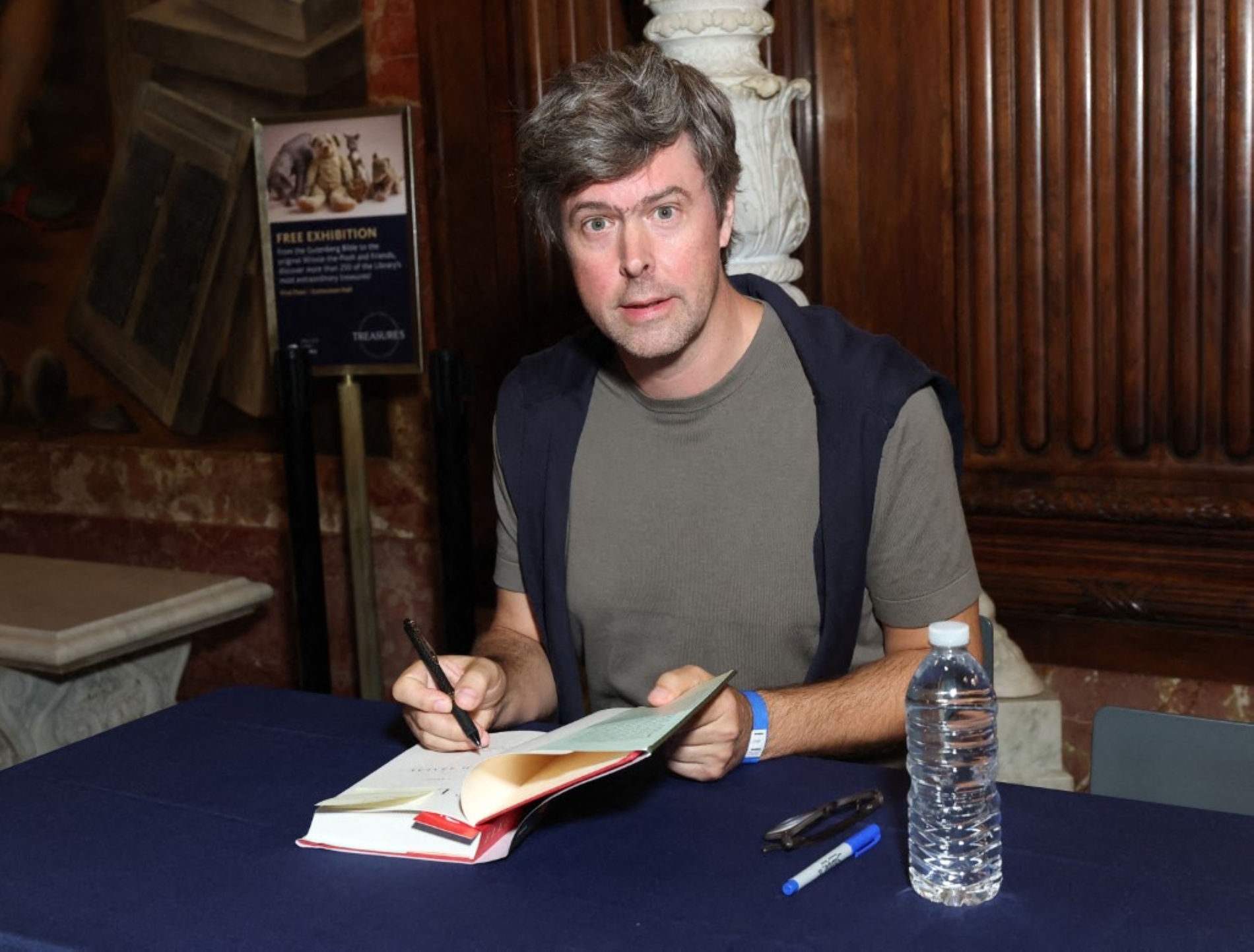

Canadian-born Hungarian-British author David Szalay is known for his ingenious storytelling and innovative approach to structuring his work. His fourth novel, All That Man, was shortlisted for a Booker Prize, as well as his latest book, Flesh, which tracks the life of an ex-convict trying to establish a new life in London, having served in the military in Iraq.

Szalay often explores money as a theme in his work, which he sees as a central force in life. In Turbulence, he interlinks a dozen short stories set around global aviation, the first and last featuring London’s Gatwick airport. In an interview with Al Majalla, he explains how he decides which details to include and which to leave out, the kind of story arcs he prefers, and what it feels like to be back on the Booker shortlist.

This is the conversation.

All That Man Is and Turbulence both employ interlinked story structures with multiple characters rather than a single continuous arc focused on one or two characters. How do you decide which approach you will take in your story?

There is no single moment of decision. All That Man Is started with a single story, and I decided to write others of the same length. Turbulence was originally commissioned as a short story sequence. However, I found that the linked-story form had advantages: a greater concentration on the essential and most dramatic aspects, while also allowing for a wider range of human experiences to be covered. Also, I would say that both of those books do, in fact, have ‘a single continuous arc’, that is especially important in All That Man Is.

In that book, as well, there is a sense that the nine different characters are, in some mysterious sense, a single character—or at least it raises the question of what a character or an individual really is. It’s a book that challenges some of the assumptions underlying individualism as a philosophical concept.

Critics have said that All That Man Is describes points on a story arc rather than being an arc in itself. How do you balance narrative momentum with withholding full backstories, especially when the reader senses a lack of transformative change in some characters? Is stagnation part of the point?

I wouldn’t say that stagnation was the point. I believe that most episodes of All That Man Is involve the protagonist undergoing some form of transformation. And I suppose I would again point to the work as a whole—to the way the work as a whole does have a kind of arc, a sense of development and change.

It’s true that there’s often little in the way of backstory, and that I suppose is part of the point. The backstory, or the past accidents of an individual’s life, is not particularly relevant. We’re all living the same life, would be one way of putting it. All of our lives follow the same basic trajectory, go through the same pattern or sequence of changes.

In Flesh, you examine life as a physical experience. How does this focus influence how you choose what to show versus what to suggest—particularly for emotional or spiritual states that often shy away from direct description?

Again, I think that the choice is instinctive rather than deliberate. However, it’s definitely the case that the book, despite its primary focus on physical existence, has an interest in emotional and spiritual states, and that it approaches them indirectly—they are usually (though not always) latent and implied rather than directly described. Why? Because this seemed like a more effective way of articulating them.

In Flesh, the body feels central. It’s where desire, vulnerability, and memory all collide. When you were writing, did you think of the body more as a character in itself, or as a lens to reveal who your characters really are?

I wouldn’t describe the body as a ‘lens to reveal who my characters really are’, for the simple reason that I would see the body as the single most important aspect of who they really are.

I don’t really accept the idea that people really are something other than what they appear to be. That’s why I wanted to write a book that deals with life as an immediate physical experience. There’s a sort of irreducible truth to that.

However, I didn’t—and don’t—want to be reductive in a negative sense. Obviously, our subjective experience of life is extremely complex and includes what seem to be other sorts of experience, and of course, I wanted the book to reflect that too...I hope it does. Physical experience has a kind of precedence. Everything starts with that.

How much are the geographical shifts and the changes in identity in the book intended as allegories for the broader inner uncertainties and fractured societies in contemporary Europe?

I very much wanted the book to be about contemporary Europe in a specific and detailed way. Europe is clearly in a state of enormous social and political flux. Identities are being broken down, reformed, and put under enormous pressure. In many ways, it's an alarming time. But for a novelist, of course, it feels like a kind of opportunity as well. There are some very interesting things to write about, and perhaps only the novel, as a form, has the capacity to take in those things in full.