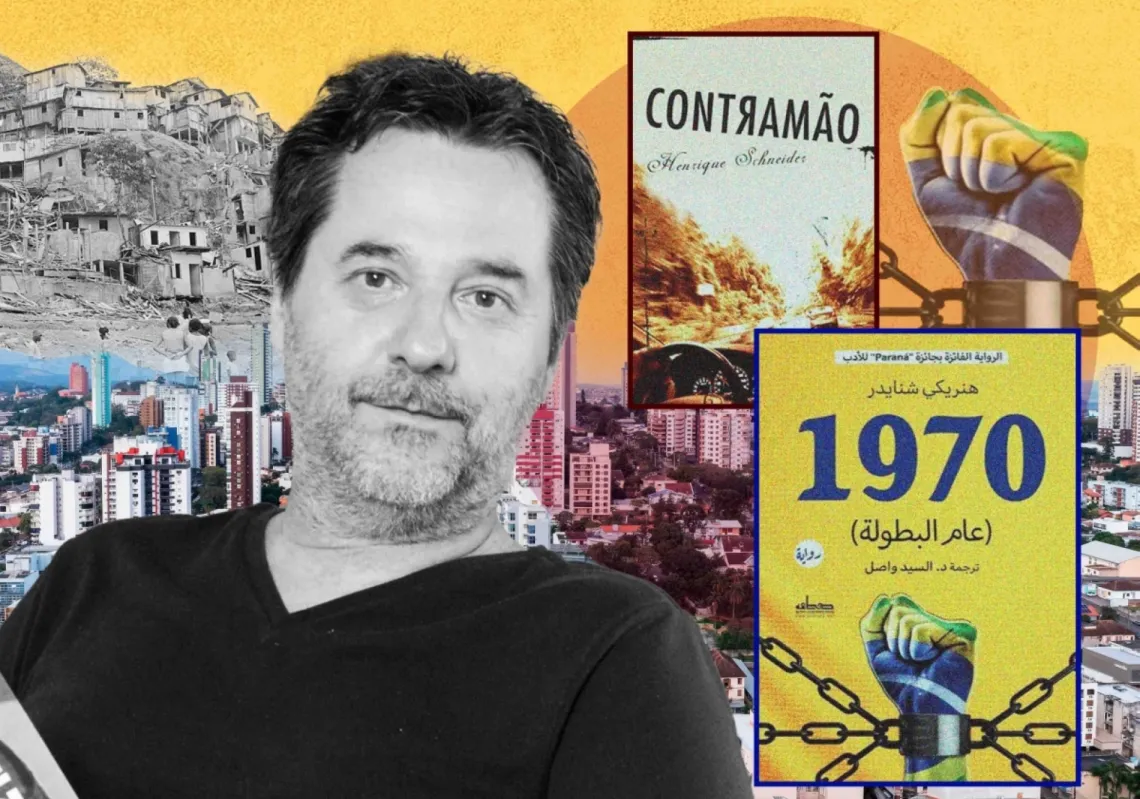

Marilù Oliva is known for storytelling from the perspective of women and a determination to bring female characters from the sidelines and into the spotlight.

The Italian author’s Warrior Trilogy—starring the character Elisa Guerra, who gives the series its name—is set in her native Bologna, and the city itself comes to life in the pages. In addition to thrillers, she has published short stories and retold famous myths.

Oliva’s latest book is about food in mythology, and she told Al Majalla that it was an “adventure” to write, in a wider discussion about her work, her sources of inspiration, and why literature and history do not align.

This is the conversation.

In your book Atlante Goloso del Mito, or Atlas of Greed in Myth, how did you combine your passion for myth and your knowledge of ancient food? Was there a challenge in blending the mythological text with contemporary culinary suggestions?

Atlante Goloso del Mito was a fascinating adventure for me, as it allowed me to delve into the gastronomic culture, religion, customs, and traditions of the ancients.

Moving from the legendary to the aspects of recipes that can be applied even with contemporary ingredients was a very enjoyable challenge.

This book was born from two great passions: myth and gastronomy. Starting from a historical-anthropological foundation—what people actually ate back then, when they dined, and how they preserved food—I branched out into the mythological sphere and concluded each chapter with a tasting menu that took into account both the recipe books of the time and my own creativity.

These are healthy, colourful, and tasty dishes that reflect the spirit of an era marked by respect for nature and, therefore, a sort of involuntary green inclination.

The book concludes with a list of contemporary recipes inspired by ancient times. What is the difference between food from then and now?

The ancients had an evocative conception of the world and its produce. It was as if every element pulsated with life or was the result of a magical touch. Nothing was by chance; everything had undergone an imaginative genesis, and some foods were consumed following a specific liturgy.

The ancients deified springs and rivers. The seas, they believed, were populated by hybrid creatures with fishtails or monsters who perhaps had looked like beautiful maidens. In the Homeric poems, heroes celebrated significant moments—such as funerals, victories, or journeys—with sacrifices or an expressed wish.

What motivated you to rewrite classical myths in a female voice?

Giving voice and visibility to the women who, over the millennia, have remained on the sidelines and spoken little is important to me. My work has not been one of rewriting but of engraving: just as a stonecutter carves away marble, so I have sought to bring out the personalities of these female figures.

The Odyssey, for example, is a book in which women have a special role. But they were already there, ready to be heard, each with her own strength and character: The frivolous Calypso who wants to hold on to Odysseus as if he were her boy toy. The multifaceted Athena who watches over the hero and advises him. Circe, who, to avoid being trampled upon by men, tries to overwhelm them. Penelope is a female mirror image of her husband, as cunning and wise as he is.

They are all great women, including a slave, the nurse Eurycleia, accustomed to staying in the background, yet she, too, will prove invaluable. Without them, the hero would truly be in trouble.

How did you maintain each character's unique voice while creating a cohesive narrative that reflects your vision of heroism and tragedy?

In all my books, I have tried to maintain the original structure. I have followed the work I intended to celebrate, reworking it, drawing on my knowledge of ancient Greek, where doubts arose.

Everything I write—passages, settings, situations, the focus of dialogue—is found in the source text, but I have tried to infuse the narrative with a rhythm suited to the taste of the modern reader. With the exception of one significant license in Dido's Aeneid—allowing the survival of this magnificent queen, who, in reality, would never have killed herself for a passing man—I have allowed myself some liberties with the human soul. The aim was to give a distinct characterisation to the various female voices that punctuate the chapters.

I tried to pay attention to everything, as I was dealing with a subject that was sacred to me. The most difficult part was the constant checking and comparison with the original, so as not to betray the authenticity of the poem.