Romanian novelist Doina Ruști is known as one of the most distinctive voices in contemporary literature. She is prolific and widely translated, having written dozens of novels, including the Phanariot Manuscript, part of a trilogy, alongside various collections of short stories.

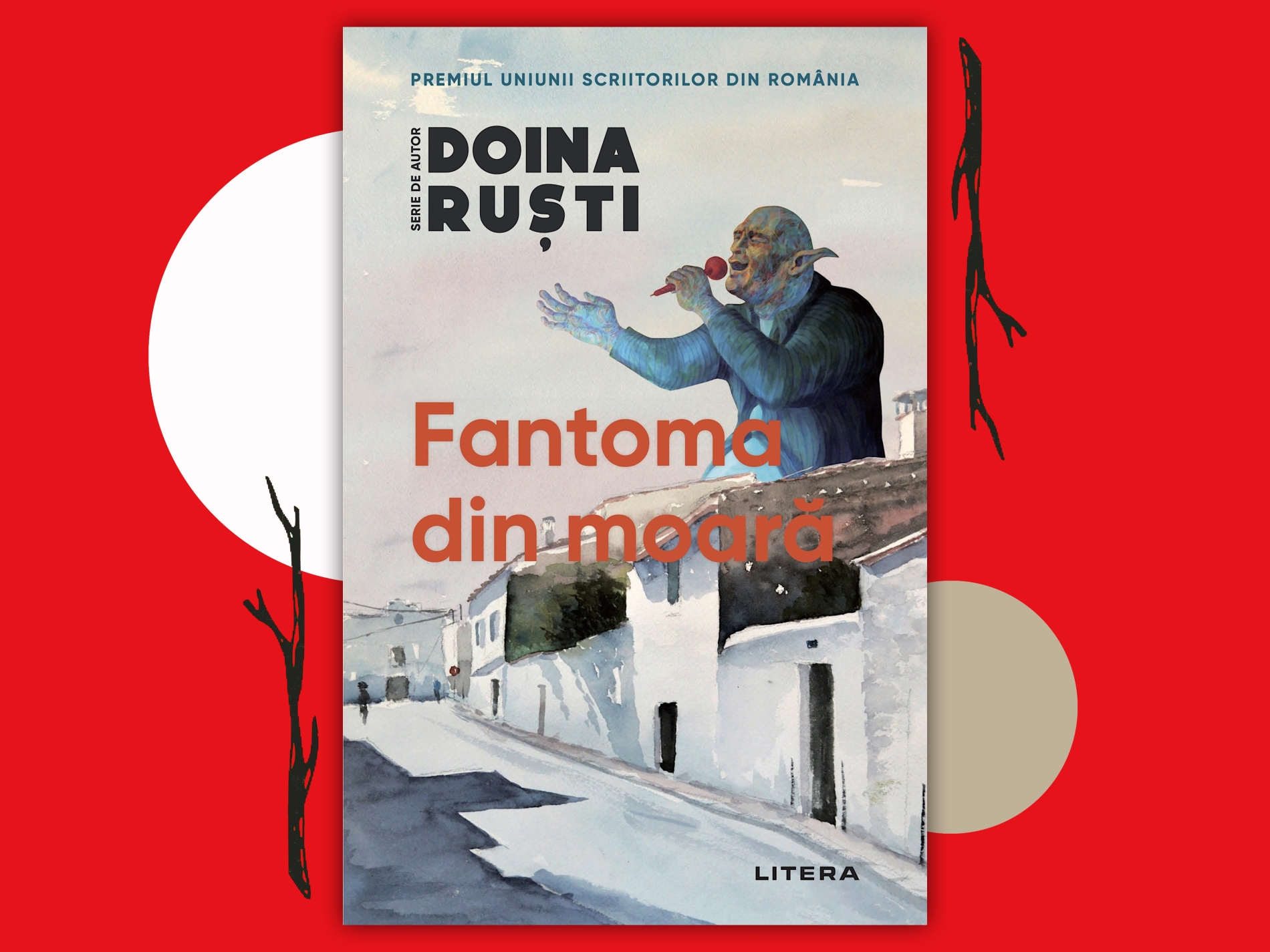

In The Ghost in the Mill, she channels the experience of her upbringing, during the chaos of the end of communism, into a parable on a society formed by oppression and overbearing rules. Meanwhile, Lizoanca at the Age of 11 is the story of a child charged with atrocities actually committed by her accusers.

When Ruști was 11 years old, her father was murdered in circumstances that remain mysterious. She has written about that in a different book, the recently published Ferenike. She spoke to Al Majalla about blending magical realism with lived experience, depicting Romanian national identity and being most famous for writing about food. This is the conversation.

In The Ghost in the Mill, you weave elements of magical realism with historical Romanian folklore. How did you balance the supernatural aspects with the socio-political realities of the communist era?

The Ghost in the Mill is my defining novel. It allowed me to enter the mill that was Romanian communism—a world in which my youth was ground away and where everything seemed controlled by an invisible master.

Since the ghost itself is a character in the novel, things weren’t very difficult. Born from the joys and sorrows of a village schoolteacher, my ghost is a projection of history —perversely historical—requiring little further explanation.

Lizoanca at the Age of 11 explores themes of childhood trauma and societal neglect. What inspired the main character, and how does she reflect broader issues in contemporary Romanian society?

Paedophilia and child abuse are rarely spoken of directly. I was deeply shaken by a newspaper article that blamed a child for an epidemic in her village. The way the story was taken up afterwards, without any compassion for the child, made me want to tackle the theme. I studied over 300 abused children, just from officially recorded and publicised cases in recent years. Then I decided to write this novel as a way of doing something for that child who had become so demonised.

The novel became my most-translated and won the Romanian Academy Prize, bringing me literary visibility. But this wasn’t just because of the theme. It is a direct, realistic novel through which I wanted to contribute to building a culture of resistance in public opinion. I don’t know if I succeeded, but the novel has been successful and new editions still appear.

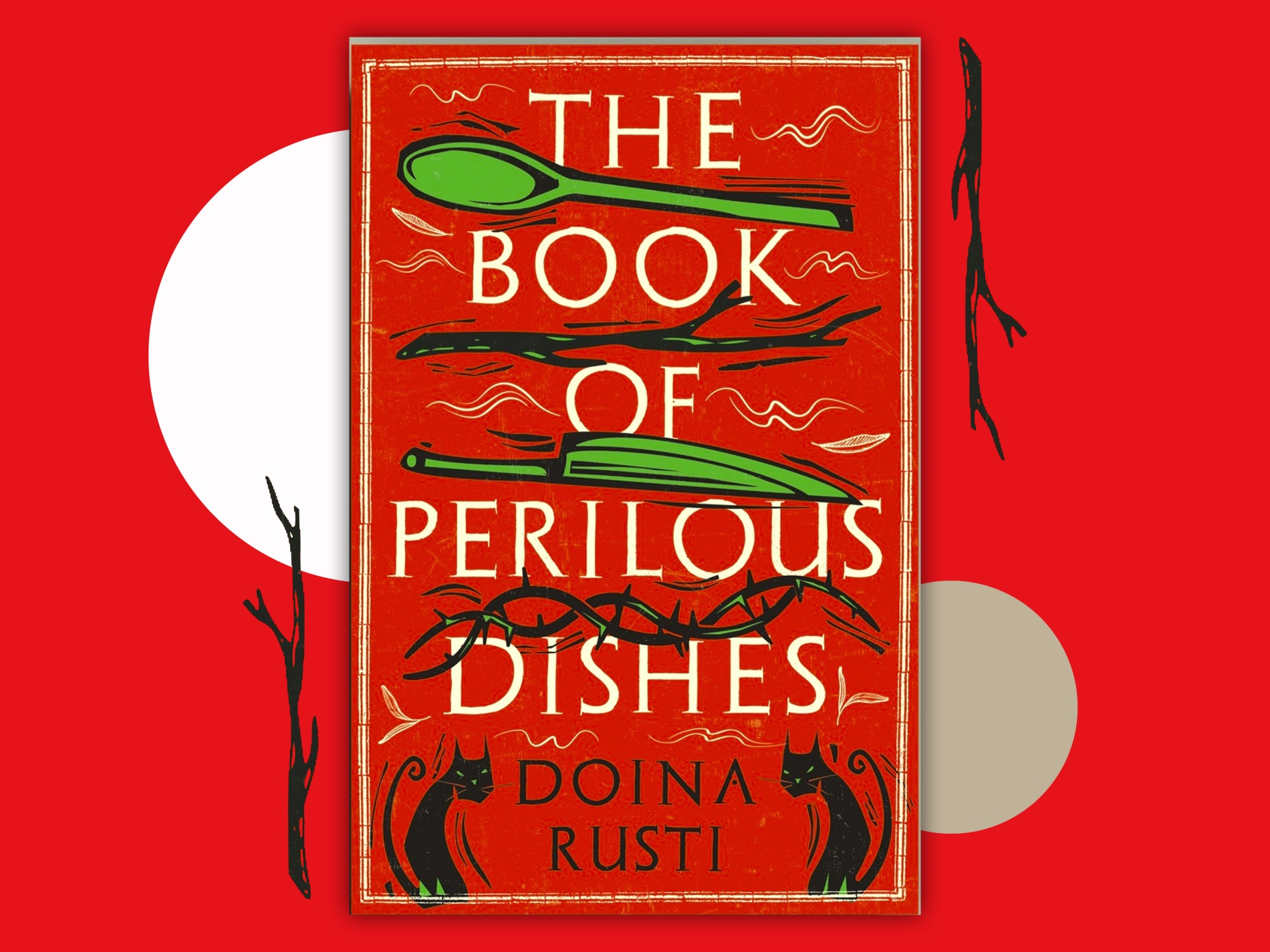

Your work, The Book of Perilous Dishes, draws on 18th-century Bucharest and culinary magic. Could you discuss how food serves as a metaphor for power, intrigue, and cultural identity in this story?

This is perhaps my best-known novel, since it was translated into English. It brings forward the story of an enslaved cook in the 18th century. I greatly enjoyed writing this book, which also has German, Spanish, and Hungarian editions. Though the historical background is real, including the cook’s story, the novel is written in a fantastical register, revolving around 21 culinary and magical recipes.

I’ve always been fascinated by culinary combinations, which most directly reveal the mentality of an ethnic group. In the novel, the recipes come from an ancient culture—the Satorini—and bring together Romanian beliefs and myths. My favourite is the rose-petal cake, which sets the plot in motion. But I also adore the witch Sirka’s little cake, which is for love.

In Zogru, the immortal protagonist offers a unique lens on human history. How does this character's eternal perspective allow you to critique modern Romanian identity and the passage of time?

Indeed, beyond the story of an eternal entity, seemingly scatterbrained and picaresque, lies the loneliness of a singular being and its need to assert identity publicly. Of all my characters, Zogru is closest to me in terms of my naivety and natural proclivity for mishaps and blunders. This is also my existential pattern: a well-intentioned person, yet eternally unlucky. That’s why I enjoyed writing this novel so much.

It has been translated into French and Italian, among other major languages. Written as a tale of searching for love and destiny, much like One Thousand and One Nights, it is also a novel with a solid narrative line and a happy ending.

The Phanariot Manuscript is historical fiction with fantastical twists. What research process did you undertake to authentically portray the Phanariot era while infusing it with elements of the surreal?

I started from a real manuscript—a contract for the sale of a human being. But gradually, by linking facts together, I turned this 18th-century document into a character. My bond with it is purely emotional.

The Phanariot Manuscript is a novel about love and freedom, two concepts that meet in a shadowy zone of vanity and selfish aspirations, both of them overstrained. In love with a slave, Leun (17 years old) must give up freedom for the sake of love: according to Romanian law at that time, anyone who married a slave also became a slave, along with his whole family if he had one.

Leun faces a dilemma, and his hesitations become fabulous. The entire society, historical facts of the period, and real characters enter the dream of this ambitious adolescent. His main desire is linked to identity and self-affirmation: he belongs to a small community of Vlachs in Thessaloniki and dreams of becoming a tailor. He sets out across the Ottoman Empire, but his dreamed-of freedom collapses. The fabulation and fantastic elements enter and transform his story into a message about identity.

Romanian culture is rich with folklore and myths. How do these traditional elements influence the country’s modern writers, and how have you incorporated them to address contemporary themes in your novels?

There is a Mediterranean side to Romanian folklore, born of geography and ties to Greco-Latin antiquity. There is also a Balkan folklore, inherited from centuries of connection with lands south of the Danube. And finally, there is an autochthonous layer, consolidated culturally through the powerful Romanian folklore school of the 19th century.

Among the myths most illustrative for Romanians, I would mention stories of tricked devils, of infernal horses, of Mărțișor, and especially of catching thieves. These are based on a belief that after you’ve been robbed, you scatter ashes in the hearth—today we’d say, in the kitchen—and draw there a map of your town. You pray to the “Empress of Flies,” and the next day, on your map, a fly traces the thief’s path with a fine line leading from your house to where the thief is hiding. And that’s it, you’ve caught him!

Of course, there are also grave myths, with philosophical depth, as with all peoples: the myth of death (Miorița) or of eternal youth. But there isn’t yet a true tradition of folkloric re-evaluation in contemporary literature. Things usually stop at satire or adaptation. Romanians are very fond of international myths. As for me, I have a passion for Romanian folklore, so in nearly all my novels, there are references, themes, and especially symbols taken from local mythology.