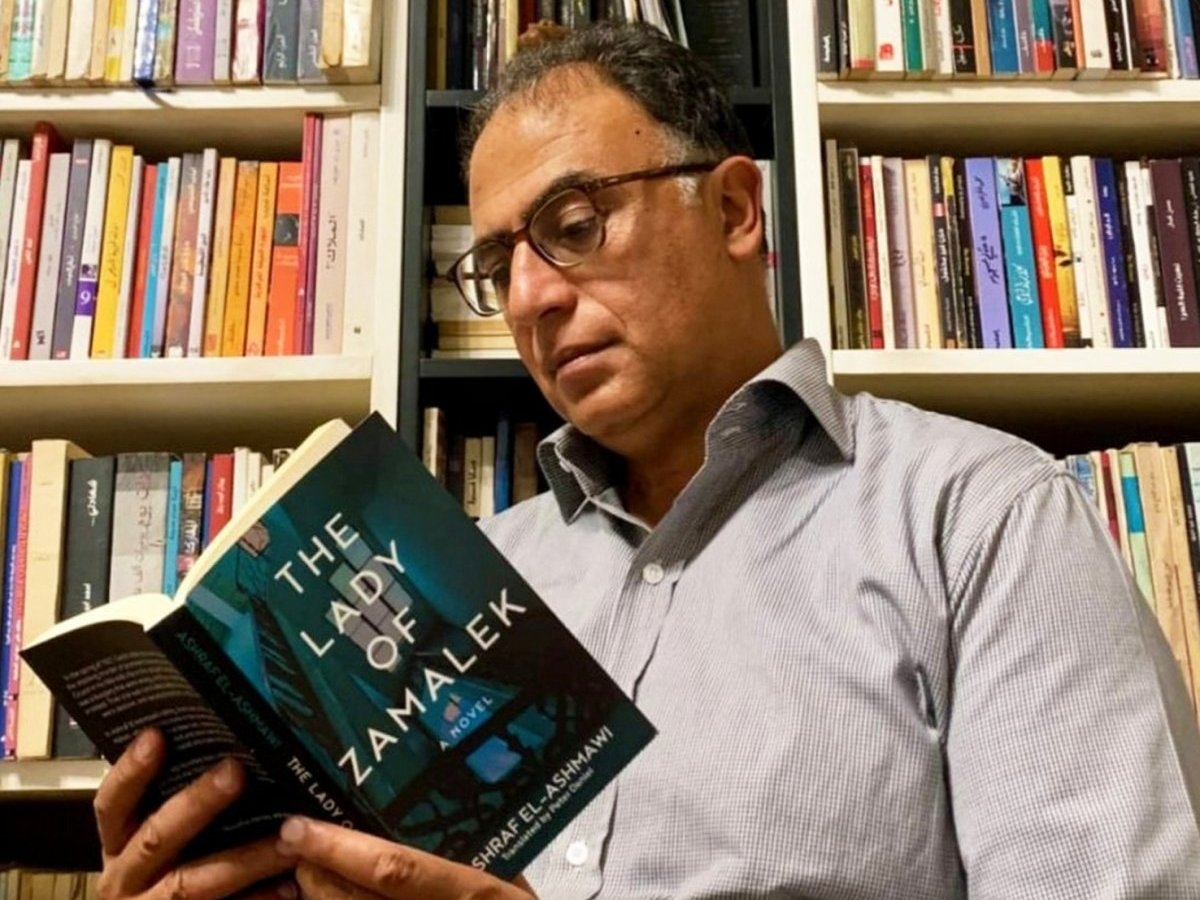

In a world where law and storytelling can intertwine, Egyptian novelist, judge, and legal scholar Ashraf el-Ashmawi has a habit of crafting narratives that reveal the depth and contradictions of the human experience. A former judge on Egypt’s Court of Appeal and legal advisor to the Supreme Council of Antiquities, el-Ashmawi also has a vivid imagination and capacity to create compelling narratives, in which he applies a legal rigour, meticulous research, and creative flair.

Born in 1966, el-Ashmawi is now a prolific novelist, whose works include The Time of the Hyenas, Toya, The Guide, The Barman, and The Shepherd’s Hounds, as well as a non-fiction book titled Legal Thefts, which explores the theft and smuggling of Egyptian antiquities and efforts to recover them. Al Majalla asked him about his journey through writing and his thoughts on the current state of Egyptian literature. Here is the conversation:

Who or what first drew you into storytelling?

Writing fiction began as a hobby and remains one, but it is far from a passing interest, because it reveals what lies within me and what I feel compelled to share with others. While it may not be my profession, it is an act of freedom, a vast space for revelation and experimentation beyond the constraints of my career.

Writing leaves a mark that reminds us we have not lived through life in silence. It is also an art of shaping meaning amid the chaos and absurdity of existence. I write for no particular audience; rather, I carry anxieties and questions that I pose to an anonymous reader with each work. I hope my belief in the illusion that writing offers immortality endures, so that each text becomes more truthful and alive than the moment it was created, and more lasting than its own time.

What made you choose the novel over other forms of art?

The novel is a form of life—a game the novelist plays with the enthusiasm of a child and the serious skill of an expert. It is comprehensive because it alone embraces all the arts within its fabric. It contains elements of theatre, poetry, philosophy, and visual art all at once, allowing the reader to live multiple lives that would be impossible in reality.

Perhaps it is the only art form that gives ample space to the smallest details. The novel reflects our daily life more closely than any other art. Cinema may come close, but it has yet to reach the depth and breadth of the novel.

The novel Born in the Zoo consists of three interconnected short novels linked by the dreams, hopes, and ambitions of the protagonists, each of whom gets entangled in situations beyond their control. How do you navigate the line between reality and fantasy in this novel?

It is very difficult to draw the line between reality and fiction in any work of fiction because every complete and truthful piece relies on both selection and imagination. I begin by choosing a certain aspect of reality, then build upon it with imagination. This makes the boundaries blurred and hard to separate. But, after completing the first draft, I often feel that the work is entirely imagined and bears little connection to the small real-life incident that originally inspired the idea.

In the novel The Secret Society of Citizens, we meet Ma’touq al-Rifai, the persecuted artist. What did you want to convey through this character and the novel?

It is difficult for any artist to fully explain what they mean by their work because part of the joy of art lies in the reactions of its audience. The artist welcomes different interpretations because this means that the idea is being conveyed in various forms to a wide range of people. If a writer defines their vision too rigidly from the start, readers might think that they had misunderstood it, which is not the case. Art, after all, carries many faces and meanings.

Many of your characters come from the margins. Why?

Marginalised people occupy my thoughts constantly. They are the majority and the victims. Their lives are often dramatic, while society remains indifferent and harsh. They live in bubbles we barely understand, even though we see them every day. Literature’s role is to diagnose reality and raise questions, although solutions belong to journalists, essayists, politicians, executives, political parties, and social researchers.

The novelist is free from all restrictions and can put a powerful spotlight on a problem because art demands it. Art is not concerned with providing solutions but with highlighting the issues that already exist, and that continue to preoccupy me. The novel presents multiple perspectives, sometimes in contradiction to one another. It is not a guide to solving problems but rather a catalogue presenting them.

Your novel Orphanelli’s Hall raises questions and issues about the July 1952 Revolution (a military coup d’état led by Mohamed Naguib and Gamal Abdel Nasser that toppled King Farouk). Why did you choose to focus on that period?

The July Revolution transformed Egypt’s social fabric, replacing the old reality with an entirely new one. It was a significant turning point in our modern history, both in what it was and what it should have been, which is why I feel compelled to focus on it. It was also a highly dramatic period that has inspired many great novels. Orphanelli’s Hall takes a different direction.

My intention was not to critique the July Revolution itself, but rather to highlight the incident of selling the king's belongings at a low price, which fits within the broader dramatic context. Orphanelli's Hall explores the idea that life resembles an auction in many ways—that was my starting point. Since Egyptian Jews dominated auction houses until 1956, I also needed to address the historical aspect.

Some critics describe the historical novel as merely a retelling of history without creativity. Do you agree?

The classic historical novel, as written by Muhammad Farid Abu Hadid, Muhammad Saeed al-Erian, and others, set the standard. Some writers have tried to imitate or write purely historical accounts, but great writers like Sanalla Ibrahim, Naguib Mahfouz, Ibrahim Abdel Majeed, Bahaa Taher, and Mansi Qandil have crafted historical novels with remarkable artistic style and deep knowledge of the novel's craft.

Writing history exactly as it happened, as seen in some contemporary works, is not novel writing, in my opinion. It is closer to documentary filmmaking—collecting historical material, presenting rare facts, and scrutinising information. A novel must be imagined; without imagination, it becomes a long article or a chapter from a history textbook.

History should always serve as the background while the imagined or even real characters move freely. The novelist's work is a vision of history and reality seen through an artistic lens and narrative. Anything else cannot be considered novel writing.

Given the rich historical legacy of the Arab world, how important is Arab history as a source in your writing?

History in general, including Arab history, is an inexhaustible source for any novelist. It serves as a living memory of glories and failures, a mirror reflecting the nature of power, societal illusions, identity struggles, citizens' stories, and inspiring narratives. Invoking history in literature is not about seeking documents to flatter but rather an effort to reinterpret and re-examine it through the lens of each writer's novel.

It is an attempt to dismantle outdated concepts so that official narratives recede and the truth remains as much as possible. In my view, history is an open space where we continually revisit and ask our contemporary questions.

You have a strong connection to place and everything related to it. How important is that in your novels?

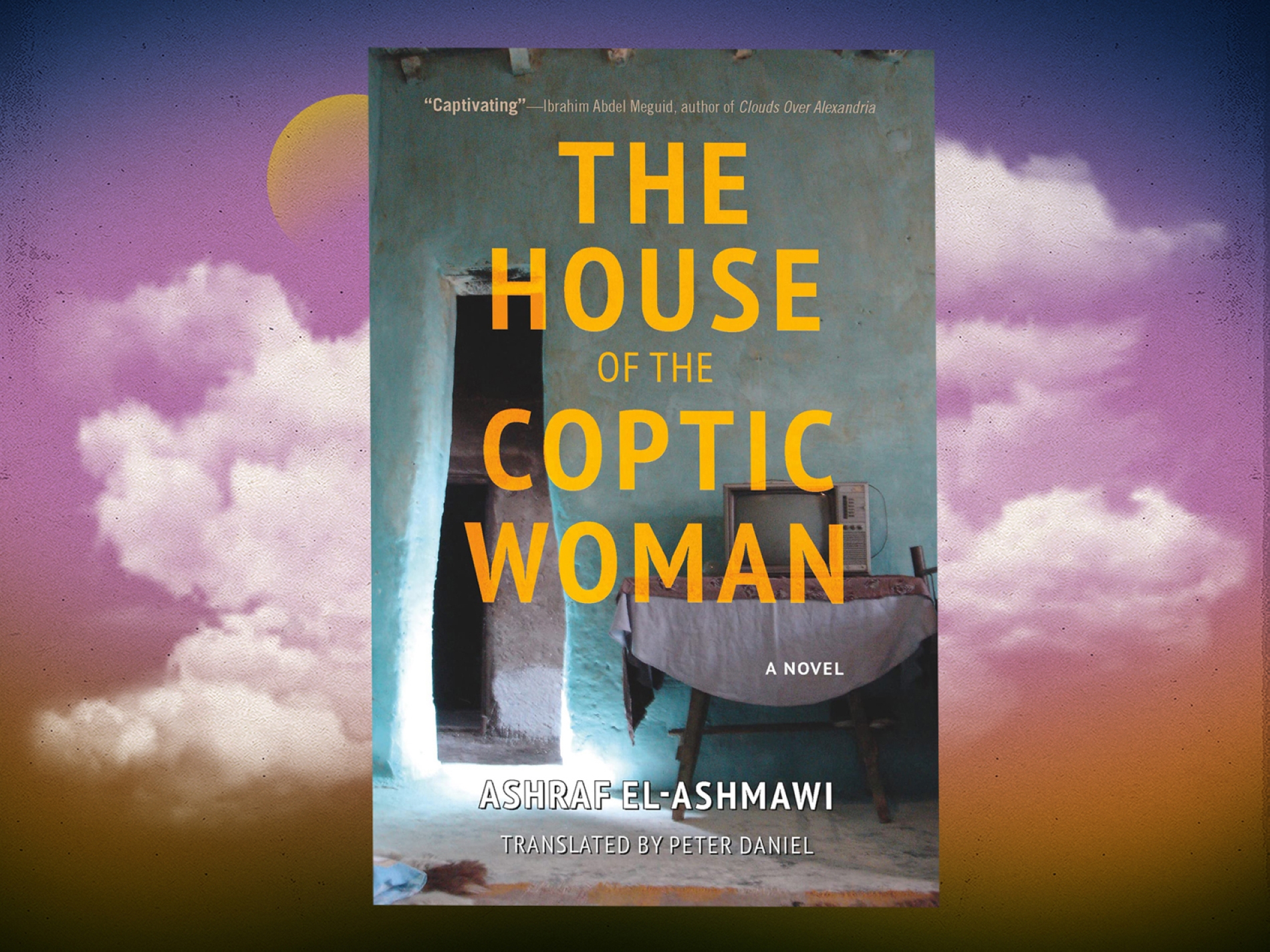

Place can be a main character in a literary work. It allows for many narrative possibilities within a novel. I used place prominently in The Barman, Orphanelli's Hall, The House of the Coptic Woman, and Born in the Zoo, each time exploring different connotations because I avoid repeating themes in my novels.

On a personal level, I am deeply attached to places, but place alone is not enough. It is people and memories that give them flesh and life beyond their mere physical structure. Place in fiction is not a neutral or silent backdrop for events; it is a living entity that shapes the consciousness of the novelist and their culture, influencing the course of the story and imparting its own spirit and characteristics.

How should we read the novel? Is it a window into the writer's most intimate ideas and convictions, or is it a presentation of ideas and visions that people whisper or speak aloud, with the novelist simply capturing them through their lens?

It is difficult to set strict rules for reading a novel, but I believe we should approach it in two ways. On one hand, the novel reveals the writer's visions, philosophy, and outlook on life, which are the primary motivations behind their writing. On the other hand, it serves as a mirror reflecting the society about which the writer writes, where people whisper their thoughts and concerns.

The novel is neither pure self-reflection nor a literal recording of daily life; it is a spacious realm where the personal and the public, the individual and the collective, overlap, making it impossible to separate a single voice. The novelist speaks through the many voices of humanity, creating a unique voice for each protagonist every time.

You have published 11 novels, some of which have won awards, and you have translated some of your works. Is the process of writing becoming more challenging?

With each new work, the next novel becomes more difficult than the one before. At first, I had what I call 'the audacity of ignorance'. I didn't know my reader and didn't care about the consequences. All I wanted was to see my name on the cover of a book. After the second novel, I began to fear the Arab reader because, frankly, they are demanding. If they read carefully, they become harsh critics.

Even now, whenever I finish one work and start another, I face a blank page and often cannot write a single sentence for many days. What I write feels inadequate. Experience accumulates, but so too does the responsibility with each new work. Sometimes I tell myself that it is better for a writer to stop when they feel they have nothing new to offer so as not to lose the trust of their readers.