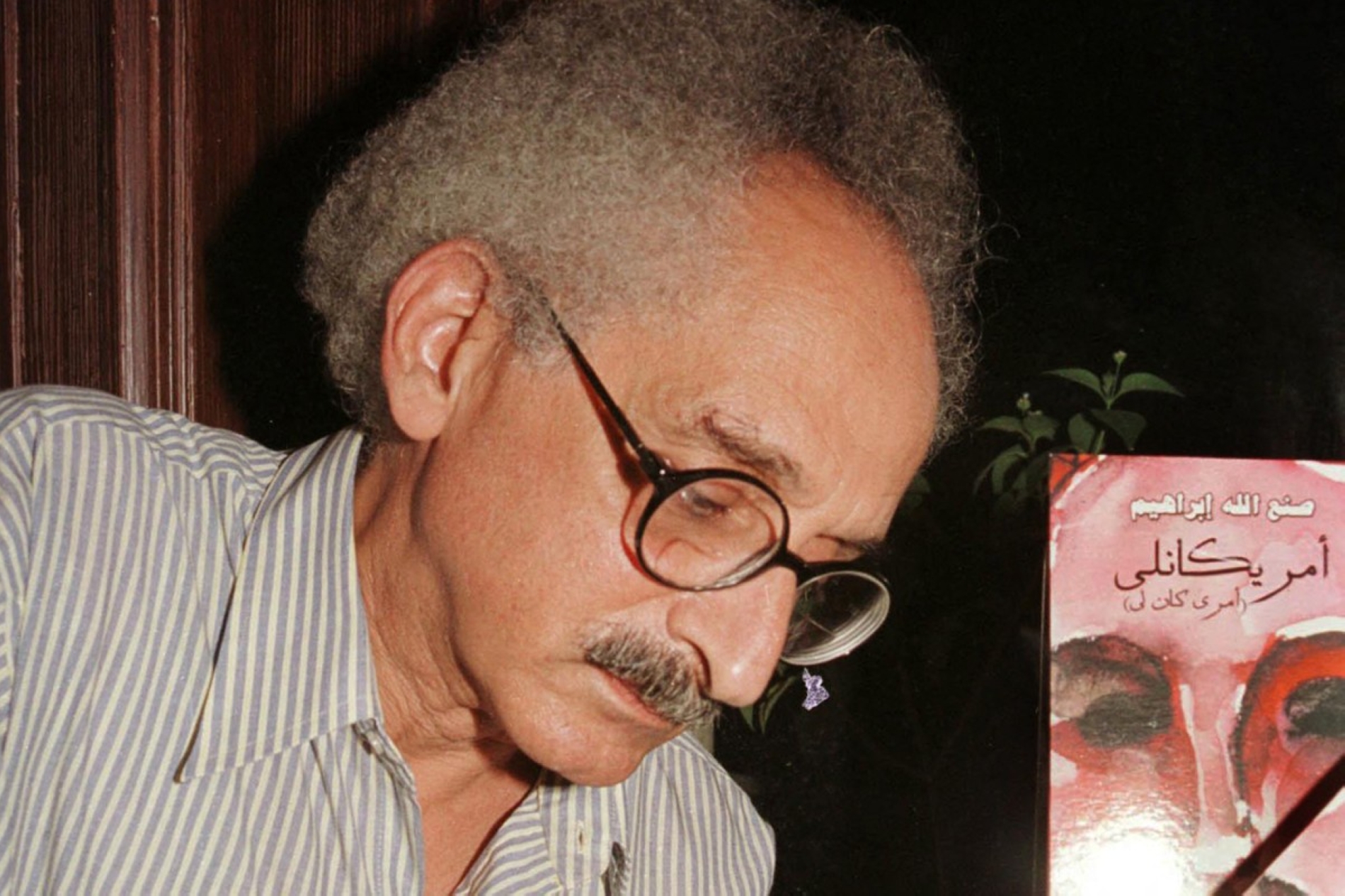

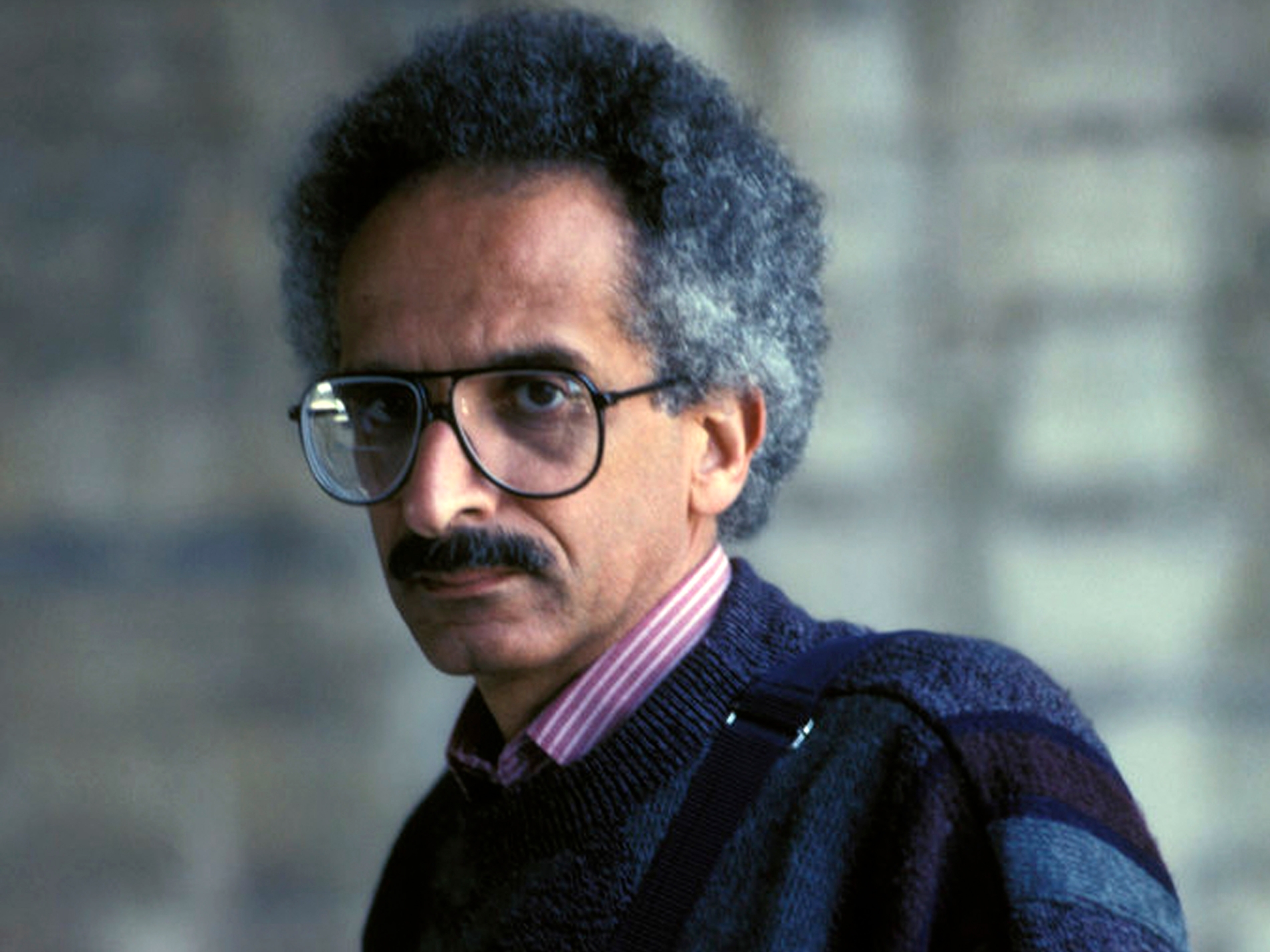

Egyptian novelist Sonallah Ibrahim, who died on 13 August 2025 at the age of 88, recognised early the gulf between the hollow rhetoric of Nasserist power—with its promises of a purified national spirit—and the stench of decay permeating daily life.

He refused to play the role of a complicit witness, asking: what is the point of glorifying the scent of flowers in literature when the stench of rot floods the streets? That same odour followed him to prison from 1959 to 1964. Upon his release, it permeated his early drafts, unfazed by the ornate language that burdened the works of his contemporaries.

Egyptian writer Yusuf Idris, the first to recognise the emergence of a distinct literary voice, objected to the original title The Stench in My Nose, which was later changed to That Smell. The first edition was published by Shi’r magazine in Beirut in 1966, in line with the modernist vision of the Shi’r group. It was promptly banned and subjected to deletions and edits in subsequent editions. A full version was only released in the 1980s.

Debunking the myth

What secured this novel a unique position on the Arab bookshelf was not merely its raw realism, intimacy, or troubled gaze at a fractured and defeated reality. Rather, it was its distinct narrative sensibility. Here was a novelist dismantling the conventional structures of fiction through radical experimentation, linguistic restraint, narrative density, and succinct sentences that delivered meaning with precision.

The approach provoked controversy, but this was a rebellious text from a dissenting writer pushing through cultural and political minefields to expose the wounds of the body and explore the dim corridors of daily life. At the same time, he devised new narrative frameworks, drawing on archives and personal observation to document events and contrast authentic history with fabricated accounts, in short, to debunk the myth.

This was narrative wandering at its freest. It bore a striking boldness in revealing confessions, truths, and defeats that had long been erased or marginalised in the mainstream Arabic novel. His writing travelled, shaped by his own experiences, from the Dhofar Rebellion in Warda, to Cairo in Zaat, to Beirut’s civil war in Beirut Beirut, to Berlin in Berlin ’69, to San Francisco in Amreekanli, and to Moscow in The Ice.

He also explored ancient Egyptian history, tracing the paths of conquerors, invaders, and colonisers, illuminating the ongoing clash between the turban and the hat. Late in his career, he looked at childhood in Stealth and his prison years in The Oasis Diaries. In The Committee, he exposed the machinery of the police state, oppression, and the layers of authoritarianism weighing society down. Through a Kafkaesque trial narrative, he depicted the total erosion of identity.

Dissecting power

At times, echoes of George Orwell resonated through this chilling absurdity, serving Ibrahim’s aim of dissecting totalitarian power. Yet, he always grounded his stories in personal experience, his own trajectory mirroring the fate of his characters as they were cast into the infernos of interrogation and arbitrary judgment.