In Japanese summer, the cicadas scream in the sweltering air, their voices tangled with the memories of August 1945. In that same heat, Hiroshima and Nagasaki were engulfed in light and silence, and the world stepped into the nuclear age. Each summer, the cicadas’ cry echoes the voices of hibakusha—the atomic bomb survivors—whose call for lasting peace continues to resonate across generations.

In 1947, Henry L. Stimson, the American Secretary of War at the time of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, wrote: “The bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki ended a war. They also made it wholly clear that we must never have another war. This is the lesson that men and leaders everywhere must learn, and I believe that when they learn it, they will find a way to lasting peace. There is no other choice.”

At that time, most Americans—including Stimson—believed the use of atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki was justified. Yet, public opinion has shifted dramatically over the decades. According to a recent Pew Research Centre survey, only 35% of Americans now believe it was justified, 31% consider them unjustified, and the rest are unsure.

Cause for sobriety

The two atomic bombs dropped on Japan by the US remain a subject of intense debate, and the world is still learning the lessons of those fateful events. Recent threats by Russian President Vladimir Putin to use tactical nuclear weapons against Ukraine suggest that not everyone has yet done so. The recent war between Israel (widely considered to be an undisclosed nuclear power) and Iran (which is enriching uranium for the same purpose) is further cause for sobriety.

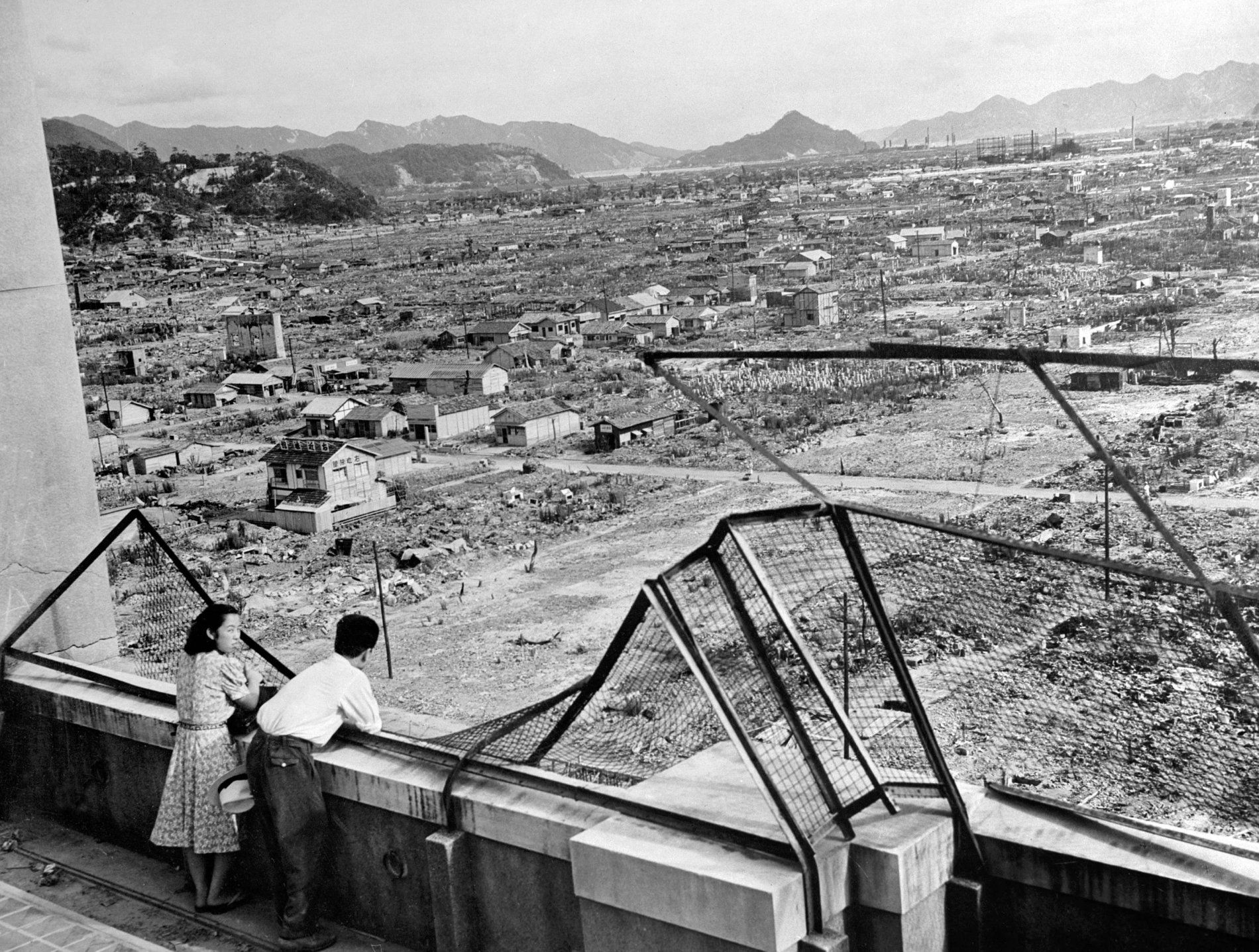

Visitors to the atomic bomb museums in Hiroshima and Nagasaki often leave profoundly moved by the scale of devastation inflicted on innocent civilians. By the end of 1945, more than 140,000 people had died in Hiroshima and 70,000 in Nagasaki; countless more have since suffered from radiation-related illnesses, including cancer, affecting not only survivors but their descendants as well.

Eight decades on, the number of living survivors continues to dwindle, yet their organisations remain steadfast in their mission: to remind the world of the urgent need to abolish nuclear weapons. Last year, the Nobel Peace Prize was awarded to Nihon Hidankyo, the Japan Confederation of A- and H-Bomb Sufferers Organisations, in recognition of its tireless campaign for a nuclear-free world.

Preventing proliferation

The Japanese peace movement thus stands at the heart of the global effort to eliminate nuclear weapons, which fundamentally reshaped conceptions of war and peace, giving rise to doctrines such as nuclear deterrence and to international agreements like the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT).

Developed during the Cold War, nuclear deterrence theory asserts that the threat of overwhelming retaliation—the logic of “mutually assured destruction” (MAD)—deters potential aggressors and maintains peace. Nuclear deterrence remains highly relevant. With doubts about US President Donald Trump’s commitment to NATO, European members of the alliance increased their defence budgets and have pursued joint French and British nuclear security initiatives.

The NPT was designed to limit the spread of nuclear-armed states, prevent proliferation, promote peaceful nuclear cooperation, and support eventual disarmament. Since it took effect in 1970, North Korea has withdrawn and acquired nuclear warheads, while China has rapidly expanded its nuclear arsenal (heading towards 1,500 warheads by 2035), creating anxieties about a new arms race.

A nuclear Middle East

Despite apparent tensions between the peace movement for nuclear abolition and advocates of deterrence and non-proliferation, these three frameworks are intimately interconnected. The profound sense of devastation, fear, and anxiety experienced by atomic bomb survivors lies at the core of nuclear deterrence theory and the objectives of the NPT alike.

From the perspective of Tokyo, the Middle East presents an intriguing contrast. The deep yearning for peace that motivates many Japanese survivors is missing, even as Israel and Iran trade direct blows, both pursuing a policy of nuclear ambiguity. As such, the prospect of a Middle East free of nuclear weapons still appears remote.

Should we find solace in the fact that the Middle East has not yet suffered from the deployment of nuclear weapons, or even faced an open challenge? East Asia cannot claim such fortune, with North Korea's ongoing nuclear and missile development and China's rapid increase in stockpiling of nuclear warheads.

Israel's nuclear ambiguity stems from a 1969 understanding between Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir and US President Richard Nixon. The United States quietly accepted Israel as a nuclear state, while Israel pledged restraint—not to test nuclear weapons and not to be the first to introduce them overtly to the region. This arrangement, however, has stymied progress toward a Middle East free from nuclear weapons.