Others have been far more critical. In a Wall Street Journal opinion piece titled “China Is the Real Sick Man of Asia,” Walter Russell Mead, a professor at Bard College, suggested that China’s “less than impressive” management of the crisis would reinforce “a trend for global companies to ‘de-Sinicize’ their supply chains.” The use of the term “sick man of Asia” in the headline caused particular umbrage and provided a pretext for the expulsion of three Wall Street Journal reporters from China. Chinese Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Geng Shuang condemned the use of “racially discriminatory language,” to which U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo responded with a defense of the free press.

The rapid politicization of the new coronavirus, and particularly of China’s role in containing it, has historical precedents. From the bubonic plague at the end of the nineteenth century to HIV/AIDS in the 1990s to SARS in 2002–3, Western observers have long viewed China’s responses to epidemic crises as indices of its relative political and economic openness. China’s management of disease has also been crucial to how Chinese citizens have viewed their nation and how the Chinese state has reaffirmed its authority.

PLAGUED BY DEFEAT

Between 1894 and 1950, an estimated 15 million people died of bubonic plague in a pandemic that began in China. The disease spread from Yunnan, on China’s southwest border, to the Pearl River Delta, with Hong Kong serving as its global launch pad. Many Western commentators were convinced that the “plague germ” had incubated in China’s crowded cities. These critics took the absence of modern sanitation as an indication that the Qing dynasty was incapable of governing. Disease, they concluded, had revealed the political system for what it was: moribund and in need of fundamental reform.

The plague hit China at a time when rival imperial powers were competing to enlarge their spheres of influence. In 1894, Japan went to war with the Qing over control of the Korean Peninsula. China’s defeat and its loss of Korea as a vassal state exposed the country’s inability to modernize; the Qing army and navy were simply no match for Japan’s remodeled forces. Then, in 1899, U.S. Secretary of State John Hay published his “Open Door Note,” which attempted to create a framework for competing foreign interests in China and protect China’s recently weakened territorial integrity. But the proliferation of imperial networks and the push to open up China’s markets had an unintended consequence: they provided the conditions for infections to globalize and a rationale for further foreign intervention in Chinese affairs.

The term “sick man of Asia” was coined in this postwar context. There was much soul-searching in China as to what had caused the country’s ignominious defeat in the Sino-Japanese War. Many reformers pointed to a pervasive cultural and political malaise, drawing on social evolutionary ideas to emphasize China’s moral and physical atrophy. Foremost among these critics was the Chinese scholar Yan Fu, an esteemed translator who was educated in the United Kingdom. In “On Strength,” an article published in a Tianjin newspaper in 1895, he likened China to a sick man in need of radical therapy. The Chinese needed to jettison debilitating habits, including opium smoking and foot-binding. The nation was a living organism locked in a competitive struggle for survival; citizens were the cells that formed this vital whole, so their physical and moral well-being was paramount.

Calls for reform grew louder in the late 1890s. The intellectual Liang Qichao reiterated Yan’s claim that as a country inhabited by “sick people,” China was a “sick nation.” Ground down by an autocratic and incompetent state, the Chinese had become sick not only morally but also physically: rampant diseases—among them plague, leprosy, tuberculosis, and smallpox—were sapping the people. Reformers called for restoring the health of China’s citizenry and rejuvenating the decrepit body politic.

Sickness and health thus provided the basis for justifying reforms that extended from the susceptible Chinese body to the enervated state. In 1923, Sun Yat-sen—the first president of the Republic of China—visited Hong Kong to give a lecture. Describing his graduation from medical school some 20 years before, Sun told his audience, “I saw that it was necessary to give up my profession of healing men and take up my part to cure the country.”

Efforts to reform China’s political and public health would outlast the Qing dynasty and the bubonic plague. In 1910, as Qing rule crumbled, the British-educated, Penang-born physician Wu Lien-teh was sent by the Chinese government to curtail the spread of pneumonic plague across Northeast China. He enacted stringent containment strategies based on modern scientific teachings: postmortems, bacteriological investigations, and mass cremations, to name a few. Wu’s program was markedly different from the response to the bubonic plague just two decades prior, when endeavors to halt the contagion were left to local charitable organizations or to the foreign officials who staffed the Imperial Maritime Customs Service with minimal oversight from the viceroy at Canton.

Just as before, however, China’s handling of the outbreak within its borders would have geopolitical implications. During the pneumonic plague outbreak, China, Japan, and Russia vied for political and economic dominance over Manchuria. With Japan rapidly modernizing and Russia bullishly expanding eastward, China’s management of the disease was an opportunity to showcase its newfound efficiency and reinforce its territorial claims. But reform came too late. In 1911, the Xinhai Revolution overthrew the Qing dynasty. Coincidentally, the springboard for the rebellion was Wuhan, the city that would become the epicenter of the COVID-19 epidemic.

THE WAR ON DISEASE

The relative openness of China’s republican period, from 1911 to 1949—characterized by freer markets, a flourishing press, newfound liberties, and lively engagement with the world—was also reflected in the country’s health sector. Chinese scientists took part in international meetings, new opportunities opened for women in health care, medical schools expanded, and a Ministry of Health was established in 1928, in part to address the rural-urban disparity in health.

That age came to an end with the communist seizure of power, led by Mao Zedong in 1949. Although the People’s Republic, like previous governments, focused on disease prevention, health, and national strength, it acted upon these concerns altogether differently. The communist government viewed health through a statist lens and as an important rationale for one-party rule. Mao’s war on disease was a case in point. Ostensibly a health campaign, the war was actually part of an ambitious social program that sought to extract undesirables, promote unity, and fight against capitalist imperialism.

During the Korean War, for example, North Korea and the Soviet Union alleged that the United States was using biological weapons to spread infectious diseases. China supported the charges, claiming that U.S. planes were dropping insects and other disease vectors to spread plague, cholera, encephalitis, and anthrax. Mao responded with a “Patriotic Hygiene Campaign” in 1952, admonishing citizens to root out and destroy invading pests: flies, mosquitoes, rats, fleas, and even dogs. Anti-bacteriological warfare measures were put in place, including quarantine stations. Although the veracity of the biological warfare allegations continues to be debated, compelling evidence suggests that the charges were fabricated as part of a concerted propaganda campaign. The accusations provided the leadership of the Chinese Communist Party with a pretext for pushing a domestic political agenda under the guise of biosecurity.

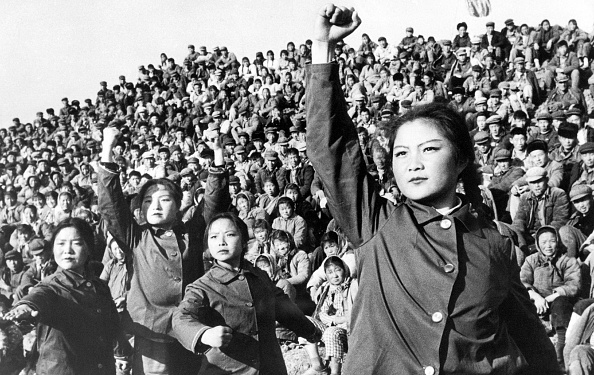

Mao continued to leverage health as a political tool during the Cultural Revolution, which was initiated in 1966 as a war against bourgeois institutions, including modern medicine. In 1964, Mao had attacked the Ministry of Health as an elite establishment; during the Cultural Revolution, he proceeded to persecute doctors and starve hospitals of support. The Cultural Revolution also created ideal conditions for infectious diseases to flourish. An outbreak of meningitis in Beijing in the late summer and fall of 1966 was soon spread across the country by the student paramilitary—the Red Guards—traveling on the railways. Chinese authorities made no attempt to contain the epidemic, since doing so would have put the brakes on the Cultural Revolution, which depended on the mass mobilization of the Red Guards to purge society of recalcitrant bourgeois elements. The United States offered assistance, which China flatly declined. By the spring of 1967, more than 160,000 people had died.

And yet, even as his government cracked down on bourgeois medicine, Mao pursued an antidisease program directed at schistosomiasis, or snail fever, an infectious disease caused by a species of parasitic flatworm. The anti-schistosomiasis campaign involved rallying large numbers of rural workers to laboriously collect and destroy snails in central and southern China. In his poem “Farewell to the God of Plague,” Mao celebrated the campaign’s success with a vision of restoring to life ghostly villages “choked with weeds.” Ultimately, however, the campaign failed to live up to Mao’s expectations: schistosomiasis remains endemic in China.

The communist state offloaded its responsibility for health onto the collective. In 1968, the “barefoot doctor” program became national policy. Villagers were recruited as part-time paramedics and underwent basic health-care training. They were given access to vaccines but otherwise received minimal state support. This putative from-the-ground-up vision of health helped inspire a global shift: in 1978, the countries that gathered at the WHO International Conference on Primary Health Care adopted the Declaration of Alma-Ata, which upheld health as a basic human right and emphasized community-based health care for all. Ironically, this affirmation of Mao’s legacy took place precisely as his successor, Deng Xiaoping, was introducing economic reforms. China’s health-care system would be one of the first areas earmarked for change.

WHISTLEBLOWERS AND ECONOMIC REFORM

China’s reform era coincided with the rise of new infectious diseases, such as HIV/AIDS. The first indigenous cases of HIV/AIDS in China appeared in Yunnan among heroin users, but by the early years of this century, infection was increasingly sexually transmitted. A booming plasma economy in the 1990s further fueled the epidemic. Third parties paid donors in impoverished rural areas for blood, from which they extracted plasma to sell to biotech companies. The residual blood was then returned to donors. As a cost-saving practice, blood from different donors was often mixed in the same centrifuges. The result was a sharp increase in infectious diseases contracted through cross-contaminated blood. More than one million people in China are estimated to have contracted HIV/AIDS.

The blood contamination scandal set the pattern for future infectious disease crises: rumors of an epidemic, attempts at a cover-up, an exposé by a medical whistleblower, followed by an official admission of the problem and draconian containment measures to mitigate the damage. In the case of the plasma scandal, the whistleblower, medical researcher Shuping Wang, brought contamination to the attention of officials in Henan, the worst-affected province. The officials attempted to deny and cover up the crisis, but news soon leaked to the international media. The plasma collection centers were finally closed for “rectification” in 1996.

The Western media, however, had already portrayed the contamination scandal as illustrative of China’s poor regulation and endemic corruption. Moreover, the episode exposed the awkward cohabitation of rampant capitalism and authoritarianism in post-Mao China: a toxic mixture of unregulated markets, patchy provincial oversight, and overregulated governance.

Similar concerns about the state greeted a different health crisis in November 2002, when the deadly SARS virus was detected in Guangdong Province. The SARS outbreak also played out on the public stage through leaked information, cover-ups, and crackdowns. Jiang Yanyong, a physician in Beijing, revealed the state’s efforts to conceal the true number of SARS cases in an interview with The Wall Street Journal. That same day, the reporter Susan Jakes published a searing exposé in Time magazine, based on a signed statement by Jiang, under the headline, “Beijing’s SARS Attack.” These reports catalyzed a policy U-turn in China. The mayor of Beijing and the minister of public health resigned, and the government embarked on a concerted and much-publicized campaign to contain the epidemic.

SARS was a major test for China’s leadership. The outbreak threatened to derail China’s export economy. And at least initially, Beijing’s bungled response set off a panic that undermined the government’s international aspirations. China had joined the World Trade Organization in 2001, and that same year, Beijing was chosen to host the 2008 Summer Olympic Games. Membership in the WTO and hosting the Olympics were both viewed by the Chinese leadership as important platforms for promoting China’s role as a global player and for ensuring foreign investment. SARS jeopardized that. As Premier Wen Jiabao declared, “the health and security of the people, overall state of reform, development, and stability, and China’s national interest and international image are at stake.”

BACK TO THE FUTURE

Not surprisingly, many commentators have drawn parallels between SARS and the current epidemic. As with SARS, officials in the province where COVID-19 broke out first downplayed the problem, and the public accused them of a cover-up. The government cracked down on whistleblowers, such as Li Wenliang, a doctor who had tried to share information about the virus. Li was hounded by the police and died of the disease.

Chinese President Xi Jinping has set out to contain the epidemic through a campaign strikingly reminiscent of the one against SARS. The Chinese government has marshaled tens of thousands of health-care workers and military personnel in what Xi has described as a “total war.” Ding Xiangyang, the deputy secretary-general of the State Council, has called the epidemic a “battle for China” and a risk to the nation unprecedented since the founding of the People’s Republic.

This “war” has challenged Xi’s authority in some respects, but it has also provided an occasion for Xi to reaffirm his credentials as Mao’s heir. By emphasizing the scale of the crisis, Xi can affirm his reputation for resourceful and clearheaded leadership when he overcomes it. For the moment, at least, Xi’s strategy appears to be working, bolstering his support in many parts of China, if not in Hubei Province, where the disease first emerged. As China’s citizens watch the chaotic scenes of COVID-19 panic across Europe and the United States, Xi’s response to the virus suddenly looks proportionate.

But the audience for Xi’s performance is as much global as domestic. Just as in the past, whether in the time of SARS or of plague, outside observers are assessing China’s governance by its capacity to manage its health. COVID-19 has become an important test for the virtues of authoritarian governance versus those of citizen empowerment. Aware of this high-stakes diplomacy, China is reframing the narrative to emphasize the success of its mass-containment measures and downplay concerns about its initial failures. China has shared its expertise with the European Union, pledged $20 million to the WHO in its fight against the virus, dispatched medical teams and supplies to Iran, Iraq, Italy, and Serbia, and promised to help African countries meet the crisis. All at once, Xi has begun to look more like a global leader committed to health for all.

By contrast, Western states appear to be improvising. Europe faces logistical obstacles as it attempts regional lockdowns and quarantines. Free access to social media in the West is fueling what the WHO has described as a “mass infodemic,” in which overwhelming amounts of information make truth hard to discern from fiction. And in the United States, President Donald Trump, who initially talked down the threat, has ignored warnings from his own health officials and now finds himself playing catch-up to local authorities frantically seeking to mitigate the spread of infection. Although the COVID-19 epidemic is far from over, China’s brand of authoritarian statecraft gains credibility by the day, objections to the state’s lack of transparency and accountability notwithstanding.

The new coronavirus has revealed a fractured geopolitical landscape and reactivated old arguments about openness and efficiency. The virus has laid bare China’s strongman leadership, but it has also highlighted incompetencies within Western democracies. As governments of democratic states impose sweeping quarantine measures, China is hoping that its draconian style of epidemic management will prevail as the new global norm.

This article was originally published on ForeignAffairs.com.