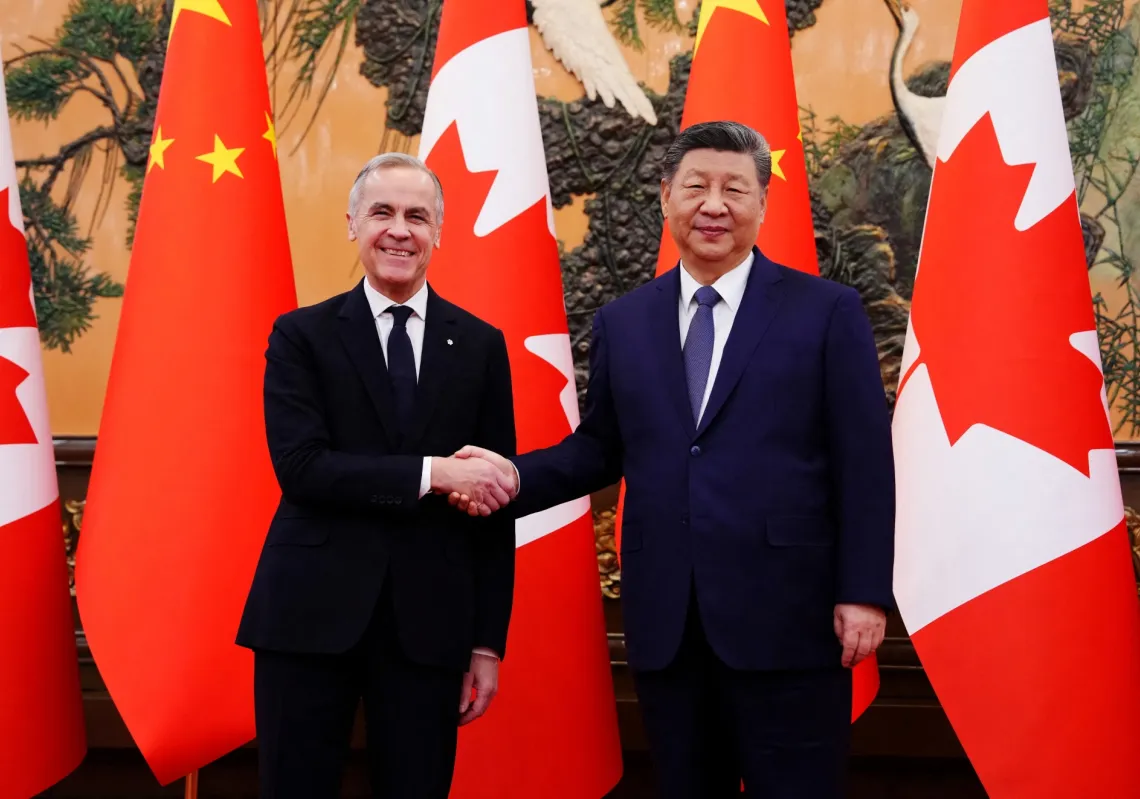

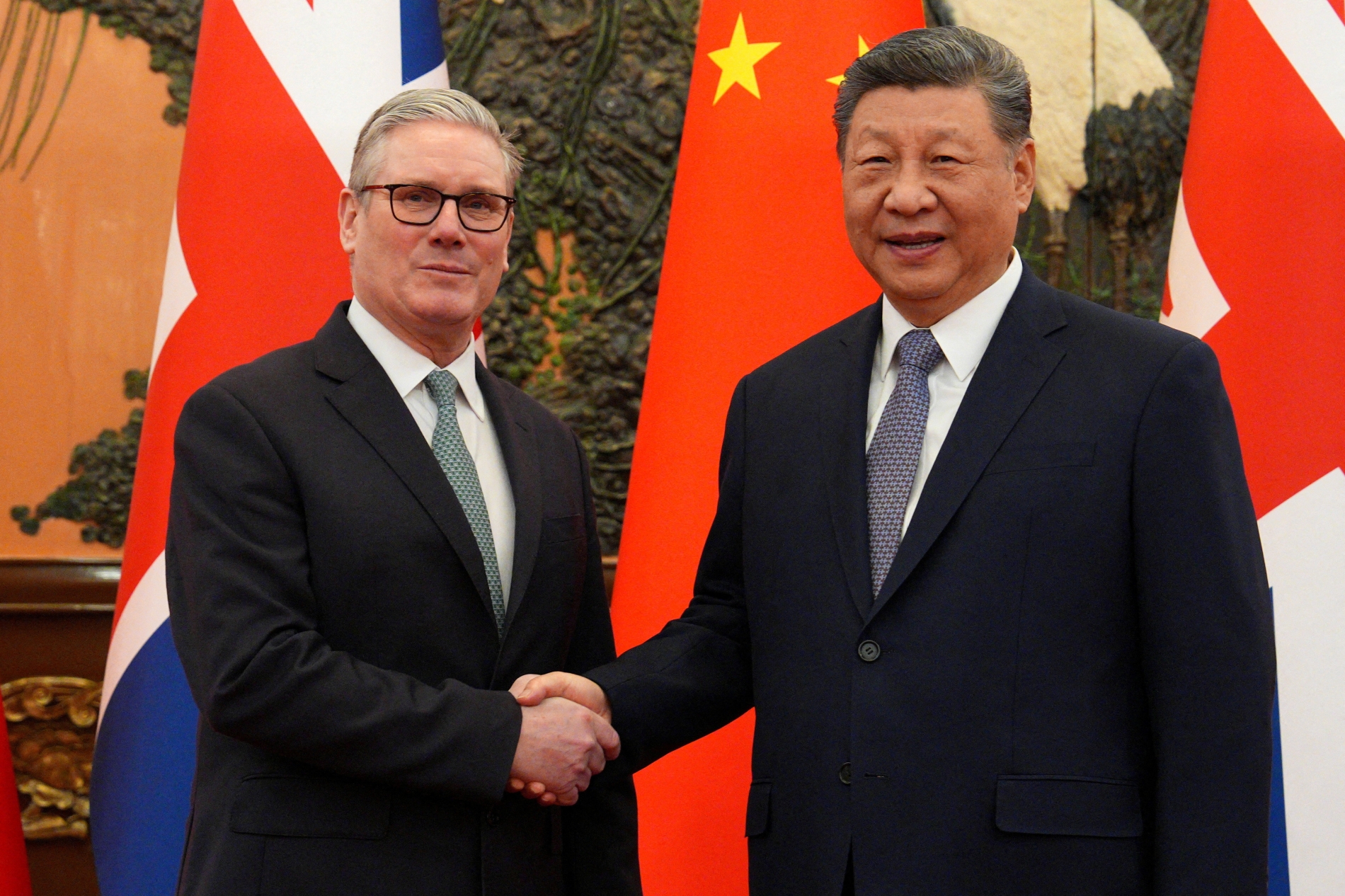

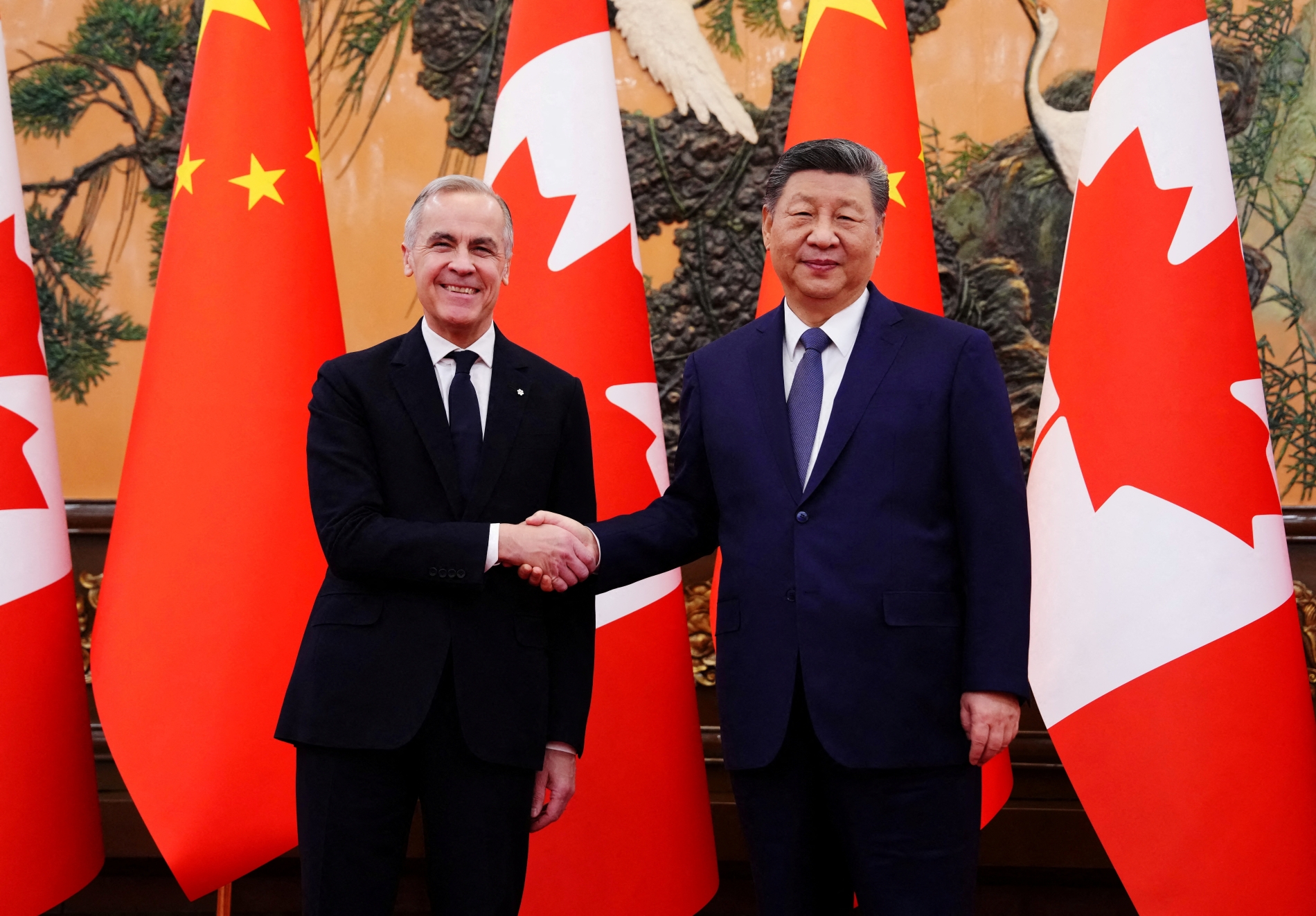

Western states’ warming ties with China would have been hard to imagine a few years ago. It was only in May 2023 that the G7, at President Joe Biden’s prompting, agreed to ‘de-risk’ from Beijing as observers began to prophesize a ‘New Cold War’ between Beijing and the West. Yet in January, two prominent G7 leaders, first Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney and now UK Prime Minister Keir Starmer, met Xi Jinping in the Chinese capital with the goal of repairing ties and improving trade relations. Emanuelle Macron was also in Beijing in December, while Frederich Merz was due there after Starmer.

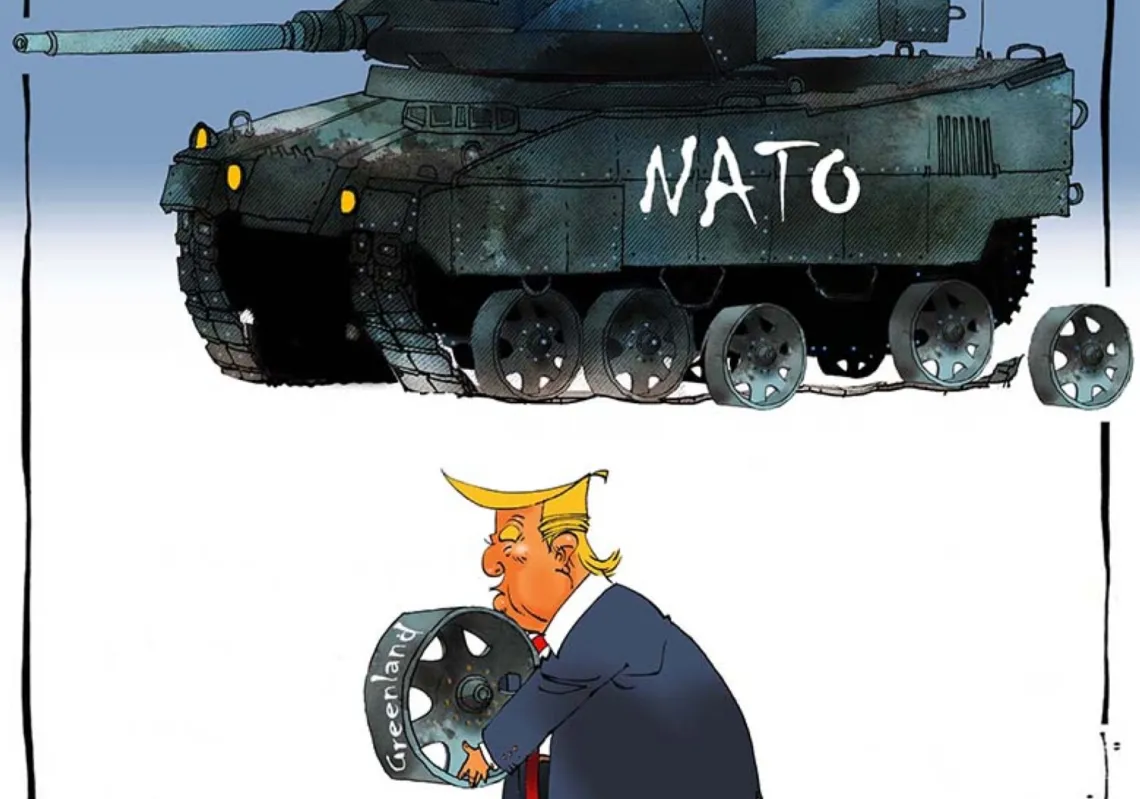

So, what’s happening? In a word, ‘Trump’. The chaos unleashed by the US president’s return to office has rattled America’s Western allies and made them seriously question the future of the transatlantic alliance. Trump’s latest antics, menacing Greenland and threatening tariffs on allies that oppose his plans, not to mention belittling NATO’s contribution to the war in Afghanistan, have convinced even previously pliable figures like Starmer to push back.

But heading to China is not a sign that Western allies are switching camps. Rather, this is the latest in a series of hedging moves. While none are willing to sever their alliance with the US, each recognises that the situation has changed drastically and that they need to pursue a range of approaches to survive Trump’s presidency.

A sobering year

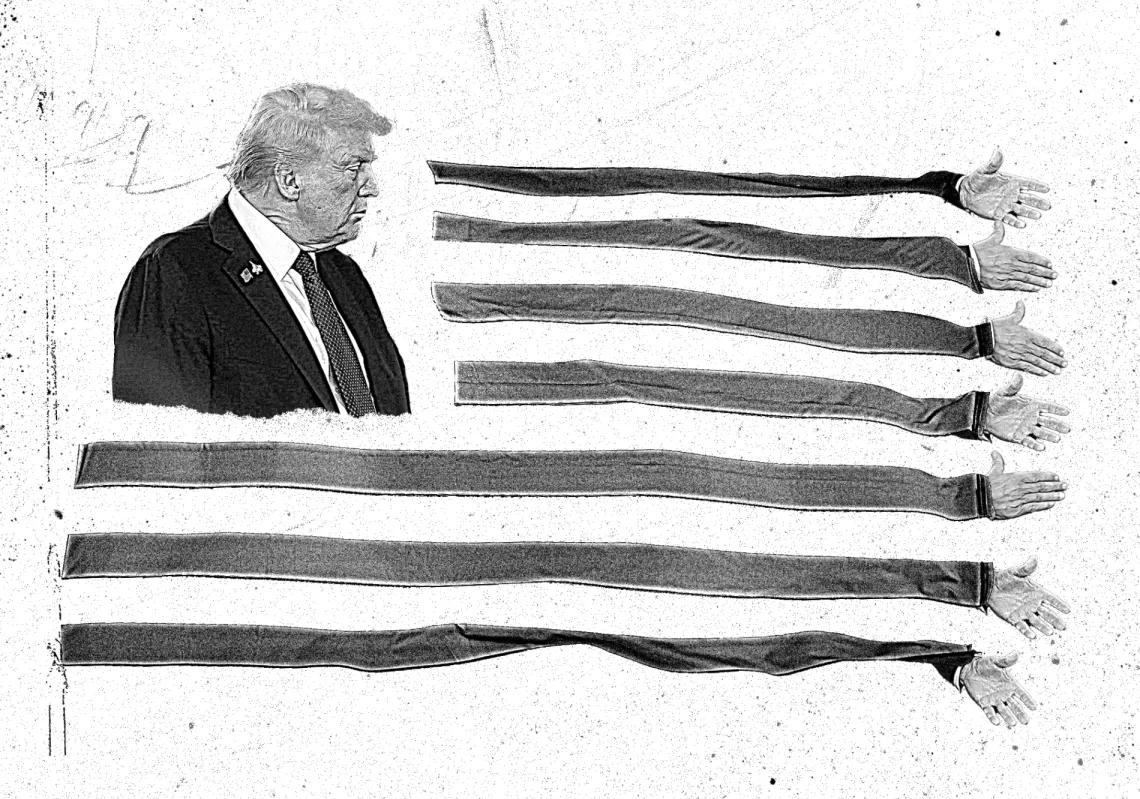

America’s western allies were not expecting a smooth ride when Donald Trump returned to the White House last January, but have still been shocked at his first year in office. Canada’s relations with its southern neighbour plummeted within weeks, with the president suggesting Canada should become its 51st state and erecting trade tariffs.

Washington’s European partners were similarly hit, the EU eventually agreeing to the Turnberry deal that saw most EU exports tariffed at 15%, while the UK negotiated 10%. Increased cost in trade might have been bearable, but European security was also compromised by Trump’s return. He has repeatedly hinted at cooling US support for Ukraine, even meeting with Vladimir Putin and endorsing several ‘peace’ plans that caved to Moscow’s demands, before later moderating.

Recently, though, Western allies have become even more alarmed. In December, the administration’s new National Security Strategy took aim at the centrist leaders in charge of most European states, claiming the continent was facing “civilisational erasure” and that Washington should “cultivate resistance” by backing its far-right parties.

Next, Trump stepped up his campaign to acquire Greenland, despite it being the sovereign territory of a NATO ally and then threatened the European states that stood by Denmark with tariffs. To compound this, he delivered a bewildering speech at Davos in which he claimed the US had “never gotten anything” from its NATO allies, and later claimed they were “a little off the frontlines” in Afghanistan. The combination quickly sobered America's Western allies up to the way they are perceived by Trump.

Projecting a united front

In response, European leaders and Canada have adopted several approaches. The first has been to stick together. This was seen most recently in the Greenland crisis, where seven NATO allies—the UK, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Sweden, Norway and Finland—all backed Denmark's and Greenland's position. This togetherness had been on display before, when in August of last year the leaders of the UK, France, Germany, Finland and Italy joined Volodymir Zelensky, NATO Secretary General Mark Rutte and EU Commission President Ursula von der Leyen in the White House to plead, successfully, with Trump to climb down on promises he’d just made to Putin on Ukraine.

The risks in this approach have been whether Western leaders can remain united, given their differing interests and if they’re undermined by pro-Trump European voices like Hungarian President Viktor Orban and other far-right politicians. However, even right-wingers like France’s Jordan Bardella opposed Trump’s claims to Greenland, stating, “When a US president threatens a European territory using trade pressure, it’s not dialogue, it is coercion.” Perhaps this means even the European right is beginning to see the threat Trump poses.

Diversify partnerships

The second approach is to diversify partnerships beyond America. A few years ago, ‘de-risking’ was discussed exclusively in relation to China, but now European leaders are talking about de-risking from the US. As well as Canada, the UK, France and Germany improving their ties with China, the EU has just signed the EU-Mercosur trade agreement with Latin American companies, which von der Leyen has called, “the largest free trade zone in the world.”

Read more: Europe and South America seal a trade pact for the Trump era

At Davos, she also spoke of a new trade agreement with Mexico, ‘advancing’ trade talks with the Philippines, Thailand, Malaysia, and the United Arab Emirates, and a “historic” trade agreement with India in the works. Frederick Kemp of the Atlantic Council reported that at the Swiss retreat, EU regulators were further discussing reducing Europe’s reliance on US technology, social media, and payment giants, and looking to other partners to increase their self-sufficiency.

Stand with Trump...on some issues

The third approach, conversely, is not to totally reject Trump. While recent events may have made Western allies think twice about the accommodationist stances they took in Trump’s first year, it is unlikely they will abandon the strategy altogether. It was notable, for example, that only Spain among the large European countries joined Latin American states (along with Russia, China and Iran) in condemning America's seizure of Nicolás Maduro. The UK, moreover, cooperated with US forces to capture a Russian-flagged oil tanker attempting to break Trump’s blockade of Venezuela.

Despite the increased tension, it’s likely that in areas of shared interest, notably Ukraine, Western players will continue to promote alignment and collaboration. Should Trump launch further strikes on Iran, as he has recently threatened, for example, don’t expect widespread condemnation from his European allies.