Over a legendary career spanning 58 years, Youssef Chahine directed around 40 films, including several shorts and documentaries. On the centenary of his birth, Al Majalla highlights some of the many standout films of the Egyptian director's illustrious career.

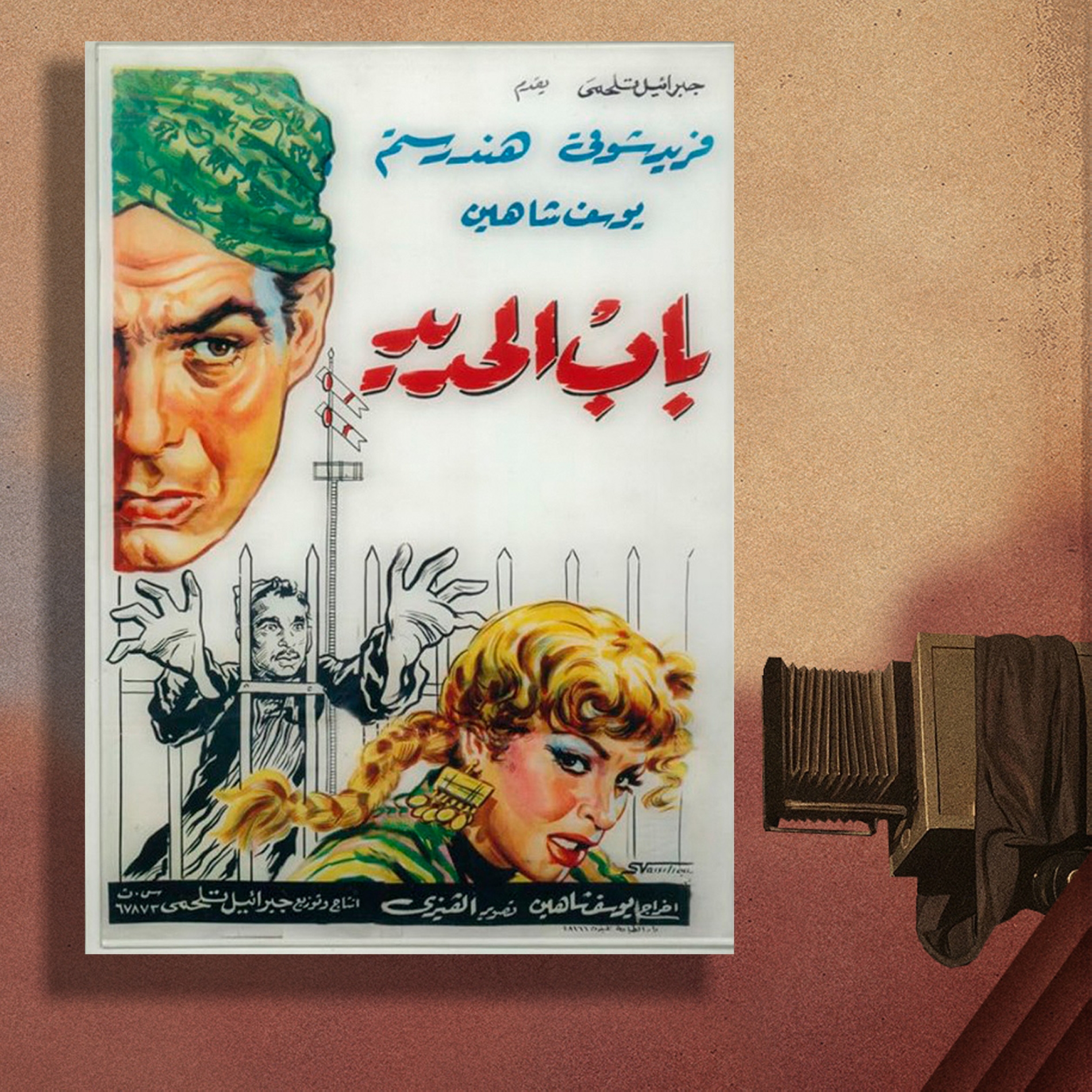

Cairo Station

Screenplay: Abdel Hay Adeeb

Producer: Gabriel Talhami

Starring: Hind Rostom, Farid Shawqi, Youssef Chahine

Released in 1958, Cairo Station is considered one of the most distinguished films in Egyptian cinema, not only for its historical importance but also as a pivotal moment in Youssef Chahine’s artistic development. While Chahine acknowledged his debt to Italian neorealism, particularly Vittorio De Sica’s Bicycle Thieves (1948), he created a form of realism entirely his own. His version was imbued with a shimmering, dreamlike quality, shifting between sensuality and lyricism.

This unique style enabled him to merge the personal with the collective. Rather than simply depicting reality, he reimagined it. The train station becomes a psychological stage, a setting in which the characters’ hidden desires are revealed, especially those of Qanawi, as trains arrive and depart.

With a screenplay that was both bold and deceptively simple, written by Abdel Hay Adeeb, Chahine moved away from the security of conventional drama and entered a more unsettled, vulnerable territory. Here he constructed a psychological universe of rare subtlety, one he would seldom revisit with the same intensity in later years.

Through Qanawi, Chahine realised a long-standing aspiration to act, delivering a performance so unique that it left a lasting impression on audiences. This broke from the dominant pattern in Egyptian cinema, where films often served merely as vehicles for star power. For this reason, Cairo Station remains the director’s most recognisable work among the broader public.

Yet there is another layer, perhaps not even fully recognised by Chahine himself, that reveals a form of self-portrait within the film. Qanawi bears more than a passing resemblance to Chahine. Beyond their shared stammer, Qanawi symbolises the filmmaker at a crucial juncture in his career. Up to that point, Chahine’s films had largely remained within traditional boundaries, despite their ambition.

In contrast, Hanouma can be seen as a personification of cinema itself—specifically, the popular and commercial cinema that embraced the likes of “Abu Sre’e” Farid Shawqi, dubbed “King of the Terzo,” while mocking the troubled, introspective cinema represented by Qanawi, the unstable outsider.

In this light, Qanawi’s limp acts as a visual and psychological metaphor for Chahine's own anxieties, doubts and perhaps even feelings of inadequacy as he sought to develop a new cinematic language that was still taking shape.

Despite the film’s celebrated status today, it was a commercial failure at the time. The response was so hostile that some cinema-goers vandalised the venue in protest. Makeup artist Mohamed Ashoub recalled that a group of Farid Shawqi’s fans sent him a letter offering financial assistance if hardship had led him to accept such a role. They ended the message with a line both affectionate and reproachful: “Don’t ever do that again.”

Not even the star power of two of the era’s biggest names could salvage the film’s commercial fortunes. Audiences were left bewildered—by Hind Rostom’s unfamiliar appearance and by the absence of the narrative structure they had come to expect. Chahine thus established a pattern of challenging, even shocking, his audiences.

There was precedent for this: in Struggle in the Valley (1954), the execution of Sheikh Saber (Abdel Warith Assar) went ahead despite the audience’s belief in his innocence, marking a clear departure from the prevailing conventions of realism at the time.

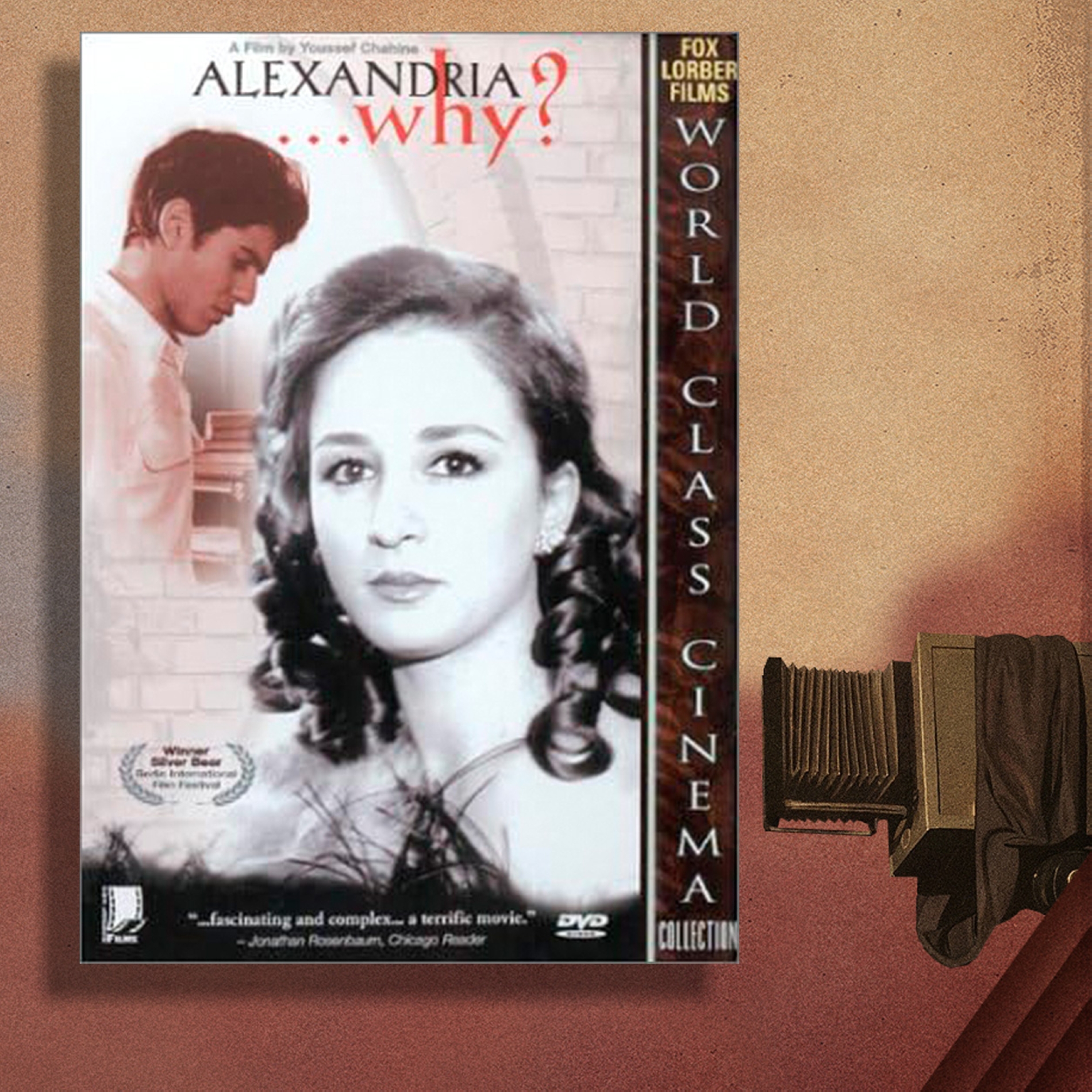

Alexandria...Why?

Screenplay: Mohsen Zayed, with contributions from the director

Production: Misr International Films

Starring: Mohsen Mohieddin, Mahmoud El-Meligi, Mohsena Tawfik, Farid Shawqi

Youssef Chahine was born on 25 January 1926 in Alexandria, a city he remained emotionally and intellectually bound to throughout his life. The city became the central character in his autobiographical film cycle, which began with Alexandria... Why? (1978), continued through An Egyptian Story (1982) and Alexandria Again and Forever (1989), and concluded with Alexandria...New York (2004), which was the weakest of the four.

Yet Chahine did not give the films a straightforward dramatic structure. He deconstructed them, rebuilding them into a near-circular form that ends where it began—with a nostalgic longing for formative years. Alexandria, in his hands, becomes a memory capacious enough to contain both the personal and the collective.

In Alexandria...Why?, Chahine begins with the Shakespearean dilemma “To be or not to be”, mapping the terrain of adolescence where early dreams take root within the halls of Victoria College, before his departure to study cinema at the Pasadena Playhouse in California. It is notable that Chahine assembled an exceptional cast for this foundational work of his cinematic autobiography, including emerging stars alongside the dean of Arab theatre, Youssef Wahbi, as if to underscore Alexandria’s cosmopolitan spirit.

He does not merely portray the city through a multiplicity of voices. He traces the transformation of the self—the filmmaker’s own self—as it matures, revises its ambitions and embarks on a kind of enclosed voyage of self-discovery that reconsiders even its relationship with cinema. Film becomes a confessional lens through which he holds himself and his intellectual milieu to account.

In a striking scene from An Egyptian Story, the real Hanouma confronts Yehia/Chahine, telling him that his connection to them never extended beyond fictional invention, dismissing his work as make-believe: “like the black paste you use in makeup to smudge your face... but we have the real tar.”

In another scene from Alexandria Again and Forever, Chahine breaks the fourth wall to insult the audience, declaring, “Damn you all.” While some interpreted this moment as reflective of the perceived arrogance of his cinema, others praised its boldness, noting that the insult was directed at himself as much as anyone else—whether for his abandonment of Hanouma or for his disdain toward what might be termed popular consciousness.

Chahine constructed his quartet in the spirit of major literary projects that celebrated place as the bedrock of their fictional worlds. A clear parallel can be drawn with Lawrence Durrell’s Alexandria Quartet, where the city emerges as a polyphonic space—one shaped and reshaped by its shifting cultural fabric, filled with competing voices and layered identities.

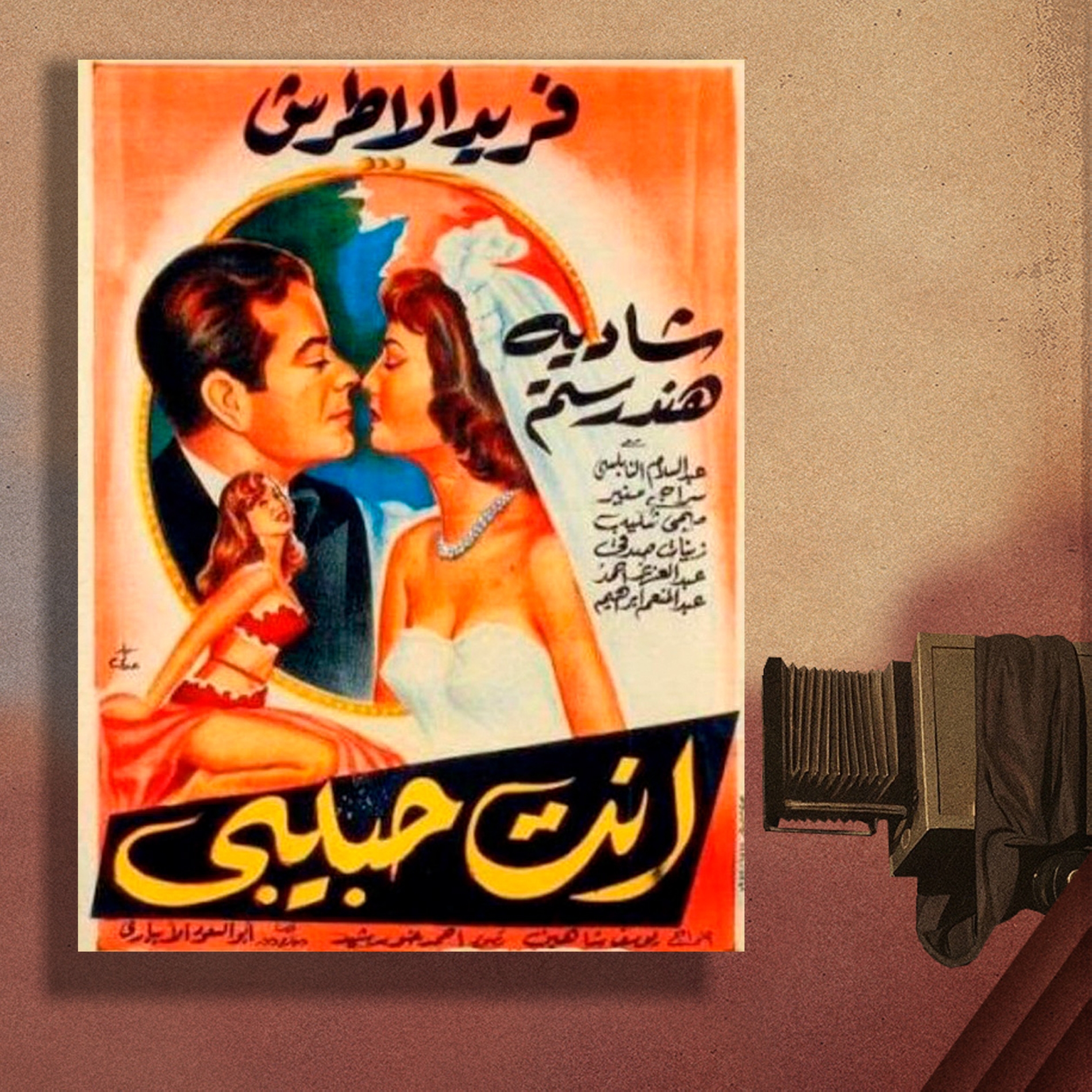

You Are My Love

Screenplay: Abu Al-Su’oud Al-Ebiary

Production: Farid Al-Atrash Films

Starring: Shadia, Farid Al-Atrash, Hind Rostom

Youssef Chahine often drew inspiration from Hollywood—visually through dramatic contrasts of light and shadow, energetic shot composition and a restless, almost anxious camera style; and structurally through layered narrative techniques and rapid editing that at times bordered on the frenetic. His filmmaking was also characterised by a strong musical sensibility, where song and dance were not decorative but integral to the dramatic progression.

Hollywood had long celebrated the musical and the spectacle film, genres that formed Chahine’s earliest cinematic attachments. It is unsurprising, then, that he dedicated The Sixth Day (1986) to a celebrated Hollywood star who embodied the unity of singing, acting and dancing, writing in the credits: “To Gene Kelly, who filled the days of our youth with joy.”

In the same film, Chahine collaborated with the poet Salah Jahin on the song “Haddouta Hattetna”, composed by Omar Khairat. He even performed in front of the camera himself—in the operetta “The God” from Alexandria Again and Forever (1989)—and danced briefly, revealing a personal relationship with performance that transcended genre and touched on his own artistic and emotional biography.

Over a career spanning 58 years, Chahine directed around 40 films, including several shorts and documentaries. Among the most notable of these is Cairo as Told by Its People (1991). It is striking that musical films constitute nearly a third of his total output. In them, he worked with some of the most celebrated singers of his time, beginning with Layla Murad in The Lady on the Train (1952), in which she performed six songs, including the beloved “From Afar, My Love, I Greet You.”