The prospect of far-right forces attaining the highest levels of power in Europe is no longer remote. Recent electoral results across the continent, and in other parts of the so-called Global North, reveal a clear shift towards the right, including its most extreme edges. There might be notable exceptions, such as the election of Zohran Mamdani as mayor of New York earlier this month, but the broader trend is unmistakable.

Since the pivotal European elections of 2024, the continent has witnessed a steady decline in the traditional support base for centrist parties, whether of the left or right. In their place, more vociferous and uncompromising movements have gained traction, alongside populist forces that often lack a coherent ideological compass.

This transformation has been driven by a growing mistrust of mainstream political elites, resistance to cultural and religious diversity, and the lingering effects of economic stagnation—conditions that have allowed the far right to reassert itself.

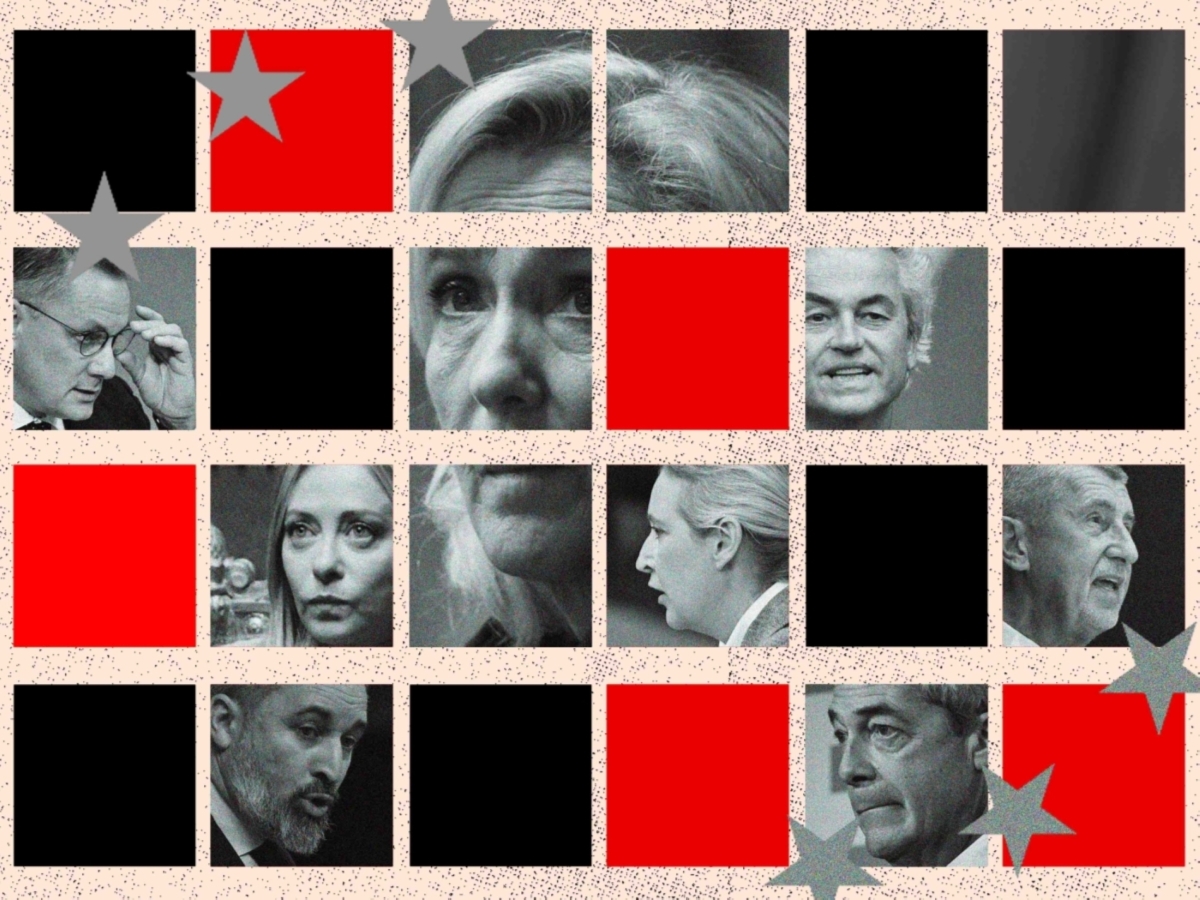

The far right’s advance continues in both its new populist and post-ideological guises, and in more traditional forms rooted in racial nationalism and identity politics. Its recent resurgence was confirmed by electoral successes in the Czech Republic and the Netherlands, building on France’s National Rally's dramatic victory in the 2024 legislative elections and Germany’s Alternative für Deutschland (AfD), which took second place in federal elections earlier this year.

A history of shifting currents

Far-right parties now govern or hold power-sharing roles in several EU countries. They lead administrations in Italy and Hungary, participate in coalitions in Finland and Slovakia, and provide parliamentary support to Sweden’s ruling government without formally joining it. Taken together, these developments signal that far-right rule is no longer theoretical—it has become an accepted political reality.

Populist parties, however, are not new to the European stage. Since the early 2000s, they have occupied a stable place in political life. Their consolidation accelerated after the 2008 financial crisis, which served as a critical moment in their emergence as a durable political force. While anti-immigration rhetoric has long been a hallmark, calls for deportation and repatriation have only recently become central themes.

Beyond established parties such as France’s National Rally—formerly the National Front and now under the joint leadership of Marine Le Pen and her deputy Jordan Bardella—a new cohort of far-right figures is rising. Éric Zemmour has launched the Reconquête movement, adding another element to France’s already crowded far-right space.

In the UK, the controversial figure Tommy Robinson (real name Stephen Christopher Yaxley-Lennon) has transformed from fringe provocateur into a mobiliser of mass discontent, and Nigel Farage continues to gain influence as leader of the Reform Party, raising the prospect of a challenge to Britain’s traditional two-party system.

In the Netherlands, far-right commentator Elss Reichts has gained visibility at the edge of a political scene already populated by extreme-right voices. In the Czech Republic, Filip Turek, leader of the Drivers’ Party, has attracted scrutiny for his provocative use of Nazi iconography. These developments signal a profound shift in Europe’s political landscape.

The entrenchment of far-right politics

From Italy to France and the UK, and from the Netherlands to Austria and Spain, Western Europe is undergoing a dramatic shift in its political balance. Recent polling data reveals a marked increase in support for far-right and populist movements, while traditional governing parties continue their steady decline. This political transformation is taking place against a backdrop of growing public frustration over sluggish growth and declining security conditions.

The rise of the far right is far from uniform. In Italy, for instance, Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni—once noted for her hardline rhetoric and former pro-Russian stance—has since adopted a pragmatic approach. She now aligns herself firmly with NATO and supports Ukraine, while endorsing liberal economic policies.

In France, the RN is caught between its previous distancing from Russia and current ambitions to forge alliances within the European Parliament. This strategic ambivalence is echoed in domestic politics, where the RN scored a major parliamentary win on 30 October by securing the repeal of the 1968 Franco-Algerian agreement, which had granted Algerians special residency and employment rights in France.