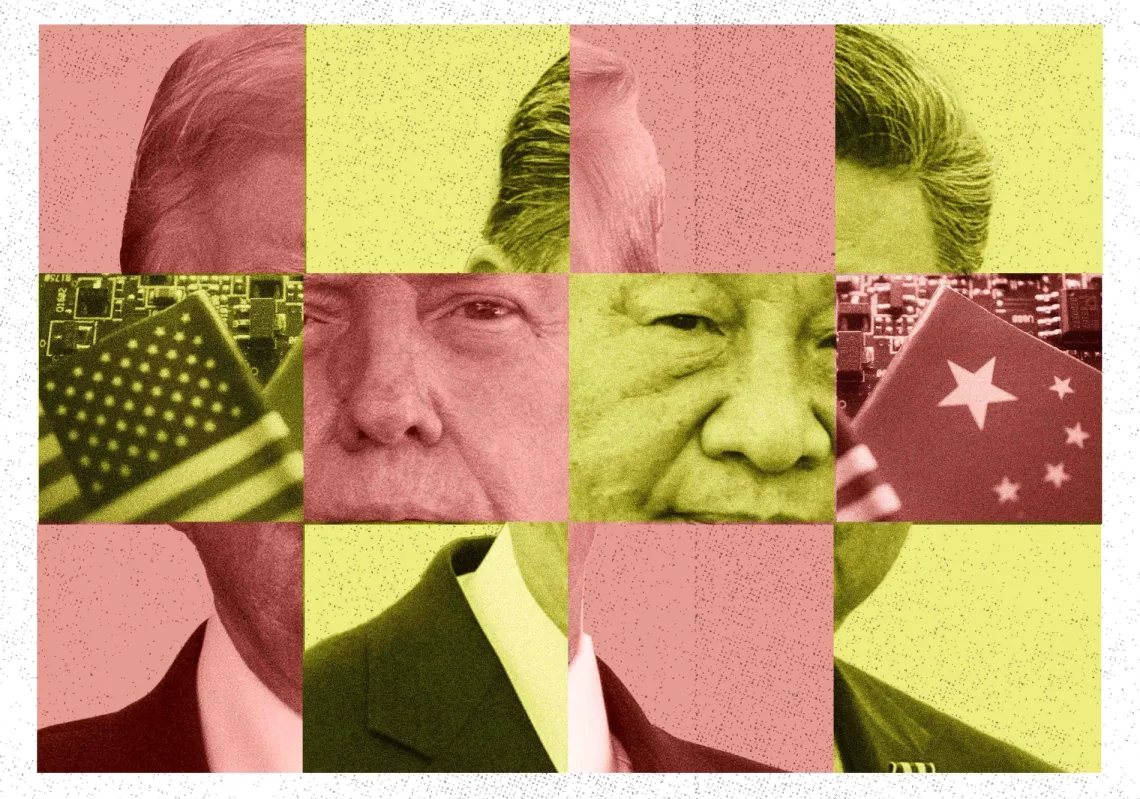

When US President Donald Trump declared on social media that “the G2 WILL BE CONVENING SHORTLY!” ahead of his October meeting with Chinese President Xi Jinping in Busan, it was more than diplomatic flattery. For some, it was a fundamental reimagining of how the United States sees its role in a post-unipolar world—one opposed to multipolarity. This approach could be seen in Trump's decision to boycott the G20 summit being held on 22-23 November in Johannesburg, South Africa.

Trump’s “G2” does not represent a return to the bipolarity of the Cold War, and his transactional recalibration of the US foreign policy does not suggest he wants to share power and governance. Rather, the “G2” framing simply advances US interests in the world without further assuming the country’s previous unipolar responsibilities. Beijing’s actual response suggests that, unlike Trump’s America, it remains committed to a world based on multilateralism, not bipolarism.

Two decades ago, in 2005, economist C. Fred Bergsten first proposed the concept of a ‘G2’ as a response to the emerging challenge of China during the Bush era. The two countries needed mechanisms to cooperate on international issues that increasingly demanded that China become a “responsible stakeholder.” The G2 idea gained traction during the 2008 Global Financial Crisis, when Beijing coordinated actions essential to arresting the global economic collapse.

Back then, Washington rejected it because ‘G2’ implied American acknowledgement of Chinese power parity. By the end of the Obama administration (2016-17), the G2 concept had been quietly buried, replaced by the rhetoric of strategic competition and the “American century”.

Symbolic validation

In Beijing, while the G2 concept never gained official recognition, it also did not lose its appeal. Xi’s China has long sought symbolic validation of its great power status, with Xi having spoken of “the rise of the East and the decline of the West”. G2 offered precisely that: recognition together with an implicit acknowledgement that China was nearing peer status with the US.

Trump’s reference to there being a “G2” in 2025 represents a different calculus entirely. Unlike the Wilsonian American foreign policy under which the G2 concept was coined to facilitate a rising power in jointly shouldering global responsibilities under US leadership, Trump’s invocation appears rooted in a much harder Jacksonian American realism.

Compared to 2005, China’s economy is now far larger. Its technology is world-leading, and its military modernisation means that it is catching up with the US. Trump appears to have concluded that containing China through technological controls and alliance pressure no longer works. So, as the old saying goes: “If you can’t beat them, join them.”

The 30 October meeting in Busan should be understood as a pause in a long US-China rivalry. This pause in escalation reflects an understanding that the pair dominate key global domains, that unilateral pressure no longer works because each side can retaliate with comparable damage, and that achieving equilibrium via economic coercion is not the same as achieving lasting partnerships.

This represents a genuine shift in American strategic posture, one rooted in realism rather than principles. Trump hailed his meeting with Xi as "amazing," not least because he gained agreement that China would buy "tremendous amounts of soybeans and other farm products". This is hardly the language of geopolitical co-equals jointly sharing responsibilities for global governance.

For the US president, the 'G2' framework is more of a convenient mechanism for negotiating bilateral transactions. The G2 framing shielded the US-China negotiations from the WTO, the EU, and other US partners. The reciprocal tariff reduction, the rare earth minerals agreement, and the fentanyl commitments are the hallmarks of Trump's transactional diplomacy. They are not building blocks for a G2 co-led world order, nor were they intended to be.