During its year-long soft opening, thousands of visitors from around the world have converged on the Grand Egyptian Museum in Giza, near Cairo’s iconic trio of pyramids, to engage with sources of intellectual and spiritual energy in a setting both compelling and immersive.

These sources may hold pathways to answers for some of today’s most pressing and perplexing questions. These extend beyond civilisational studies, archaeology, and ancient lifeways, encompassing fields such as mechanics, hydraulics, sustainable agriculture, natural resource conservation, and the interrelationship between plant and animal life.

The site, which is poised to become ‘the world’s largest museum dedicated to Egyptology,’ also sheds light on healing practices grounded in spiritual reflection and the transformative power of poetry, reasserting the value of contemplation and the ethics of language, while engaging with a host of other urgent contemporary issues.

Ahead of its official opening on 1 November, Al Majalla toured the museum’s exhibits and galleries over the course of a six-hour visit. The experience was imbued with a profound sense of awe at the enduring allure of an ancient civilisation that continues to inspire the world to this day.

The Allure of Ramses II

Since the discovery of King Ramses II’s monumental statue, standing 11 metres tall and weighing 83 tonnes, the sovereign of Upper Egypt has played an unending game of seduction, casting his spell wherever he goes.

From the moment his face was first revealed to the Italian explorer Giovanni Caviglia in 1820, to the time he—or what remained of him—came under the chisel of renowned Egyptian sculptor and academic Ahmed Osman, the wearer of the splendid crown has journeyed through Egypt’s public squares and the shifting tides of its rulers for more than a century. Discovered in six fragments, the giant statue, with the king’s legs inscribed with the names of his daughters Meritamen and Bintanat, began its odyssey in Mit Rahina, Giza, before spending decades at Ramses Station, then Bab al-Hadid, and later Tahrir Square. It has now come full circle.

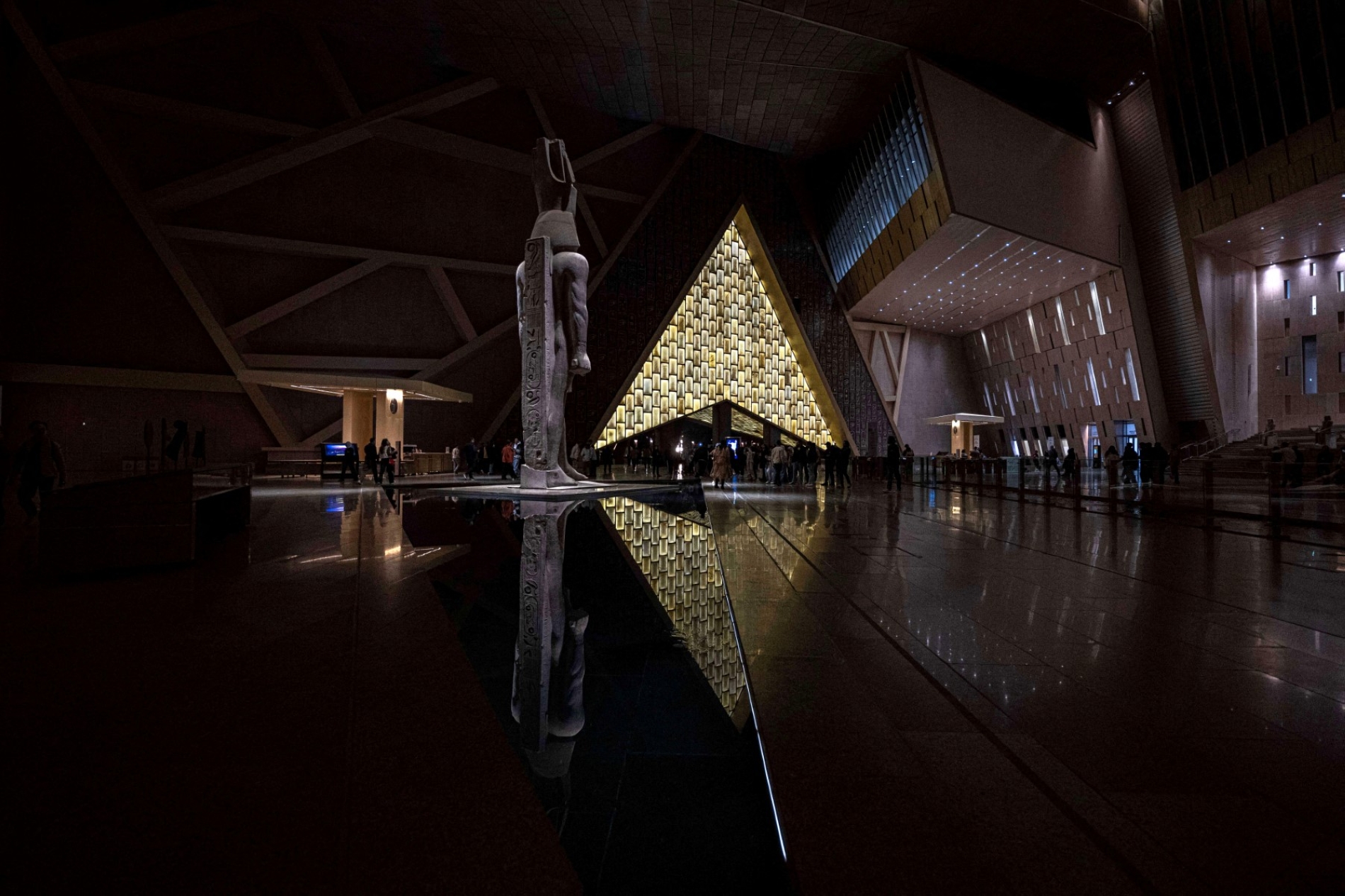

Setting aside the traditional and ever-renewing allure of pharaonic secrets and codes, the statue of Ramses II, now standing tall to welcome visitors at the entrance of the museum, draws its enchantment above all from its many journeys. Each of these movements has added a contemporary layer to its stone legacy, forging a deeper bond with the people of modern Egypt. The statue also holds scientific significance, offering lasting lessons in ancient construction and sculpting techniques that continue to inspire and perplex scholars and researchers to this day.

In the atrium, shadows drift through a ceiling adorned with contemporary geometric patterns, elegant and in tune with the space's energy. Yet even their delicate play of light fails to draw attention away from the king’s commanding presence. You must first step closer to examine the refined craftsmanship of the stone, then retreat to a distance to fully grasp the scale of the colossal statue.

Instinctively, the mind turns to calculations and the principles of geometry. It is in this fluid movement between the realms of art and science that another facet of Ramses' allure reveals itself, deepening the sense of kinship between the depths of humanity and the depths of stone.

The English author Christopher Dunn remains sceptical of theories that attribute the carving of such statues to the use of simple, traditional tools by the ancient Egyptians—tools whose application would have required immense time and effort, often implying a system of servitude. He instead favours a more challenging proposition.

"They possessed engineering knowledge that still defies our understanding," he argued in Lost Technologies of Ancient Egypt. "In the statue of Ramses II and others, the extraordinary symmetry and micron-level precision in working with stone, along with cutting marks resembling those left by high-speed saws and drills, suggest the use of advanced technology rooted in precise knowledge of engineering and mechanics."

His theories were supported by the late Egyptian archaeologist Farkhonda Hassan in her book Ancient Egyptian Technology. There, she widens the scope of inquiry beyond sculpture to include the techniques used in irrigation, agriculture, bread and food production, mining, weapons manufacturing, medicine, and pharmaceuticals.

The floating origin system

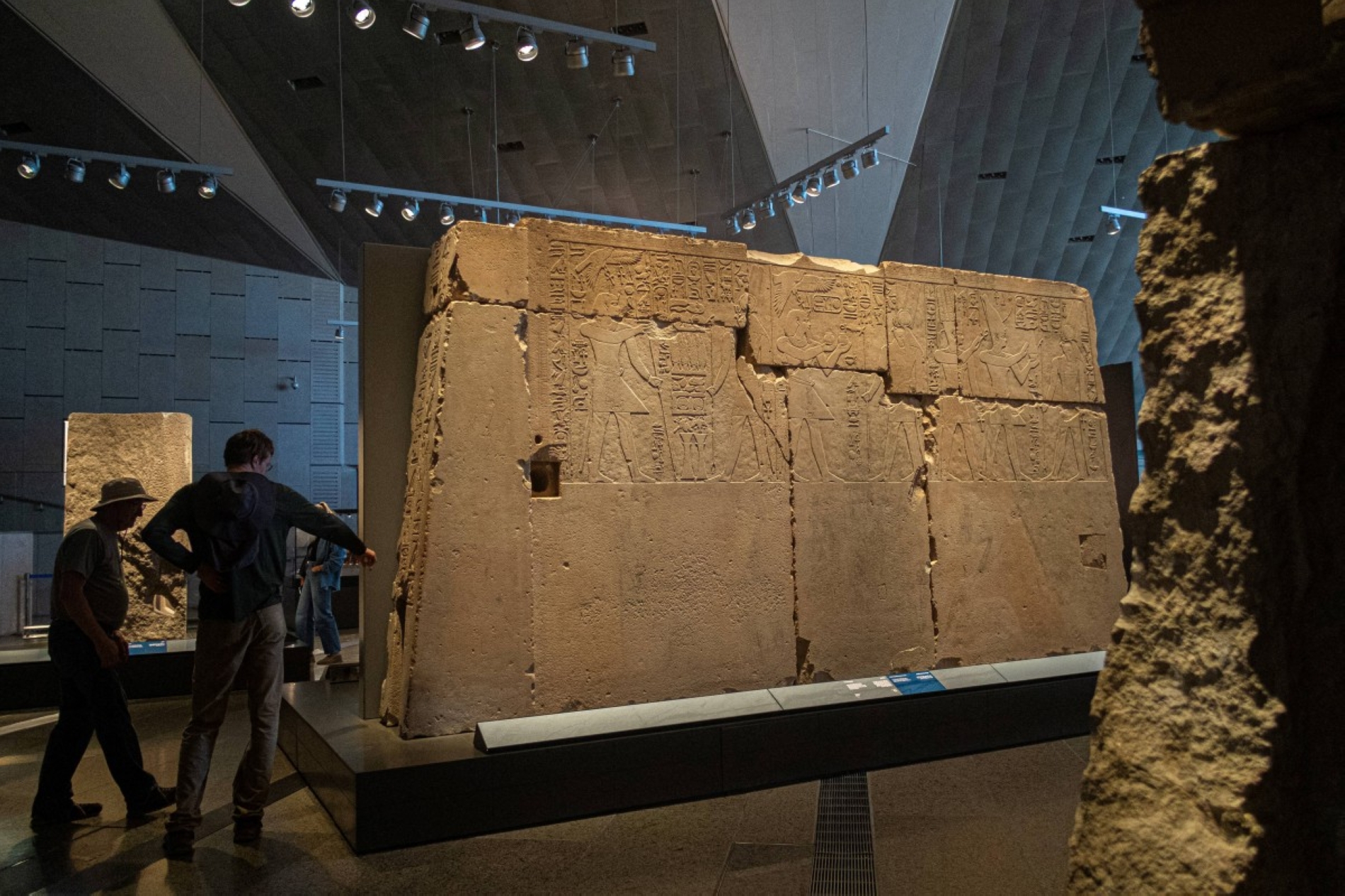

Between the museum's lower atrium and the entrance to its galleries rises a 10-metre staircase flanked by towering statues. Some of these sculptures weigh up to 35 tonnes, while others weigh in at the hundreds. They draw visitors into a maze of questions about the engineering precision required to reconcile aesthetic design with structural endurance, as well as the complex processes involved in transporting and securing such monumental works.

A glance through the large glass window at the top of the staircase reveals the three iconic Giza pyramids resting nearby. Their deliberate inclusion in the museum's visual scope reinforces the continuity of architectural excellence. The pyramids quickly dispel any lingering doubts about the engineering prowess of their builders, serving as a reminder that the ingenuity of these builders has endured across the ages.

That narrative, in fact, may begin with a small statue on display inside the museum, accompanied by diagrams. It depicts what is considered the origin of pyramid construction, the Step Pyramid of King Djoser at Saqqara. This structure is recognised as the first monumental stone building in the world, dating to around 2700 BCE. In the centuries that followed, the rulers of the Old Kingdom refined this design into the smooth-sided form of the true pyramid, culminating in the monumental scale of the Great Pyramid of Khufu.

According to a recent study published in Science Focus, the Pyramid of Djoser may have been constructed with the aid of a complex hydraulic lifting system—a principle still in use in modern engineering. The study notes that "near the pyramid's construction site, which reaches a height equivalent to a 14-storey building, water was channelled from a nearby dam and processed through a floating system that extended 400 metres and reached a depth of 27 metres. This ensured the quality of water used during the construction process."

The system, believed to have enabled the movement of massive stone blocks, likely involved pumps built within the pyramid's columns. These pumps lifted the water, which was then discharged through a stopper mechanism, allowing the process to be repeated multiple times.