*This article was first published on 22 October, and has been updated to reflect the 30 October meeting**

The leaders of the world’s two largest economies are meeting in South Korea for an Asia-Pacific summit, in the first meeting between US President Donald Trump and Chinese President Xi Jinping since the former began his second term of office in January 2025.

President Trump greeted Chinese President Xi Jinping at the beginning of their formal meeting on 30 October, saying he and Xi have a "great relationship." The two leaders are expected to discuss tariffs, fentanyl access and rare earth minerals.

Ahead of the meeting both leaders sounded optimistic about cooling trade tensions between the world's two largest economies, with Xi saying that "a few days ago, trade negotiators for both countries reached a fundamental consensus on addressing each other's primary concerns. I am willing to continue working with President Trump to lay a solid foundation for China-US relations," and also pointed out out that China's development “goes hand in hand with the vision to make America great again".

Their meeting represents a critical inflexion point for the world, not only because of the potential to resolve major economic disputes between them, but because it will help determine whether US-China competition remains manageable or cascades into total economic warfare. The latter scenario would likely have no clear victor and be a zero-sum game, dragging the rest of the world in as collateral damage.

There is no shortage of headlines about the ‘US-China trade war,’ but the phrase ‘trade war’ suggests that this is a trade war like any other, one that weaponises tariffs and export controls, for instance. In fact, it is a generational struggle for technological supremacy and control of the global economic architecture, increasingly involving reluctant third countries.

The latest skirmish took place in the Netherlands on 13 October, when the Dutch government invoked a little-used law to seize control of Nexperia, a Chinese-owned Dutch-domiciled chipmaker, citing “serious governance shortcomings” that threatened European economic security. Just days earlier, the US Department of Commerce expanded export control restrictions to encompass all global subsidiaries of companies on its entities list. This now includes Wingtech, Nexperia’s Chinese parent.

The Netherlands said there was no pressure from Washington to seize the company and that the timing was coincidental, but China was unimpressed and responded by blocking Nexperia from obtaining Chinese-made products. Nexperia’s chips, which are used in the automotive and consumer electronics industries, are manufactured in Europe but packaged in China, leading to a standoff. This is what great power competition looks like when it becomes zero-sum. It is no different in principle from Trump’s imposition of hefty tariffs on Apple’s overseas production.

Punch and counter-punch

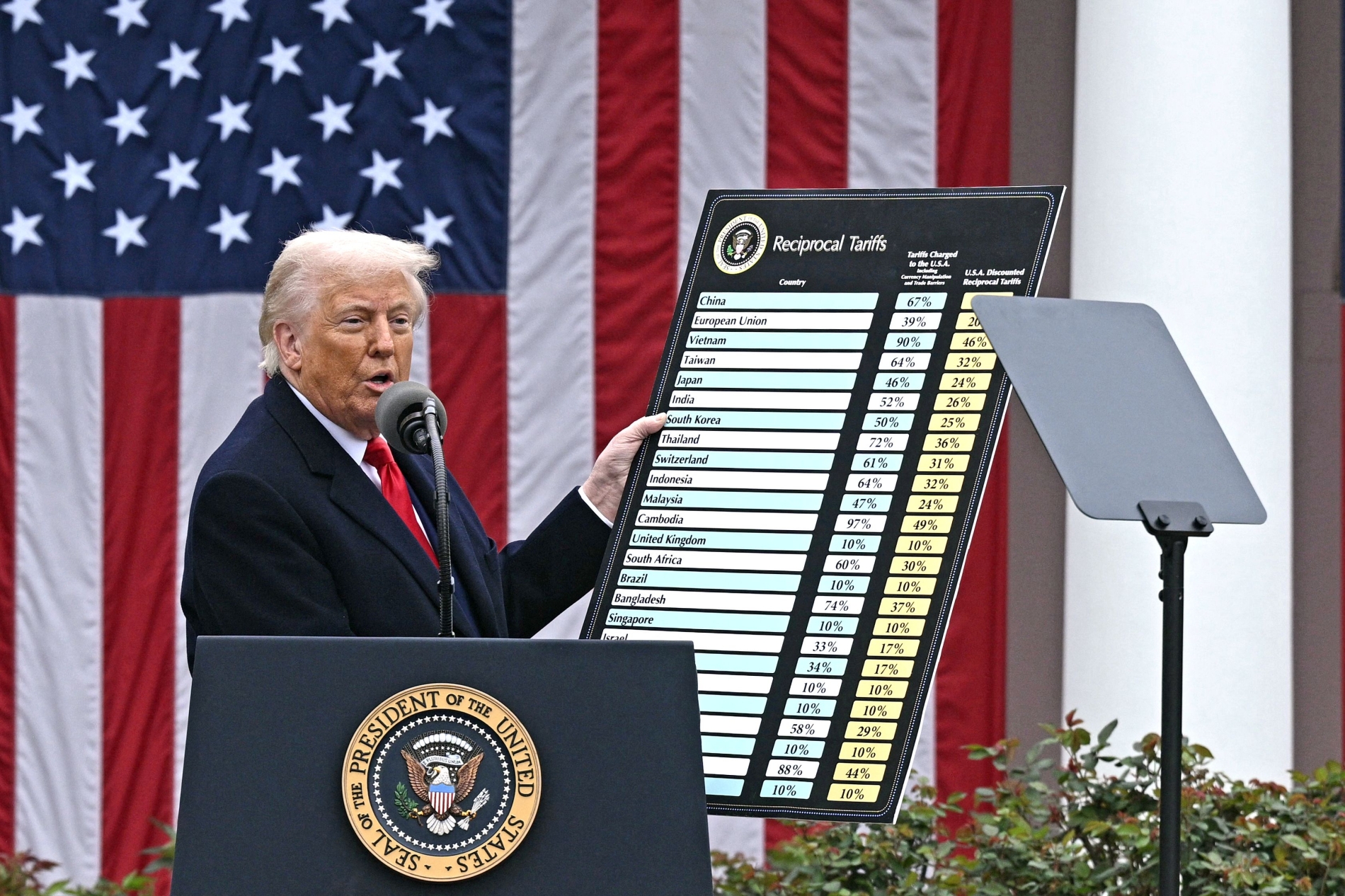

How did we get here? Most analysts trace it to Trump’s proclaimed ‘Liberation Day’ earlier this year, when he announced a 34% reciprocal tariff on Chinese goods, layered atop an existing 20% tariff he had already imposed (ostensibly due to Chinese ingredients fuelling the fentanyl drug epidemic claiming thousands of American lives) and the tariffs already imposed on Chinese goods during his first term in office.

China imposed retaliatory tariffs of up to 84%, prompting Trump to raise incremental US rates to 125% on Chinese goods. In June, a tariff ‘truce’ was struck in London, with a framework stabilising tariffs at 55% for China and 10% for the US. In a sign of good faith, China approved the sale of the US version of the popular China-owned social media app TikTok to US investors.

But last month, problems re-emerged. On 12 September, the US expanded its notorious ‘entities list’ by adding 23 Chinese subsidiaries, including chipmakers and biotech companies.

On 9 October, China responded with sweeping new export controls on rare-earth minerals, expanding restrictions to 12 of the 17 elements. Foreign companies now require special approval to export products containing even 0.1% of rare earths processed in China, with most restrictions due to take effect on 1 December. Rare-earth magnets are crucial components in chips, F-35 fighter jets, Tomahawk missiles, and drones.

China knows that the US faces critical vulnerabilities in its industrial supply chains and is willing to use its control over rare earths as leverage at the negotiating table. Interestingly, China's new export controls make it only the second country (after the US) to apply the foreign direct product rule, a mechanism that the US has used since 1959 to restrict sales of foreign-made products incorporating US components.

Beijing has learned from and adopted Washington's strategic approach, applying extraterritorial controls with global reach, and the US's retaliation has been forceful. On 10 October, Trump announced an additional 100% tariff on Chinese imports "over and above" any tariff that China is currently paying, effective from 1 November. This would cement tariff rates above 150% on Chinese imports to the US.

The US also imposed port fees of $50 per net tonne on Chinese-owned or operated vessels starting on 14 October, rising to $140 by 2028. China responded with identical fees on US vessels. These measures could fundamentally restructure global shipping lanes and force international companies to re-align trade along geopolitical fault lines.