Standing inside Galerie Saleh Barakat in Beirut, it is difficult not to feel dizzy before the overwhelming mixture of human and material fragments that fill four monumental murals, each mounted alone on the gallery’s wide white walls. These sprawling clay landscapes are barren and lifeless, stripped of humanity or vegetation. They evoke the catastrophe that befell Mosul and Aleppo.

Measuring 36 square metres in size, these epic clay installations are the art of Iraqi painter and sculptor Dia al-Azzawi, who has lived in London since 1976. Born in Baghdad in 1939, al-Azzawi decided never to return to Iraq and completed his latest work in the Jordanian capital of Amman, as Israel pursued its war of extermination in Gaza while bombing various regions of Lebanon in pursuit of Hezbollah. His focus was on the ruins of two Arab cities often described as twins: Mosul, in Iraq, and Aleppo, in Syria.

There are four murals in total, and one stands out. Titled A Forgotten Paradise, it is dominated by a deep crimson background and veiled by a black shadow, with spectral human figures portrayed in a funerary ritual. At its centre, a sculptural relief of a crucified body, which breaks perspectival, formal, and temporal boundaries with the rest of the composition. The scene is suggestive of a ceremonial and authoritarian spectacle, with Pharaonic, Babylonian, and Assyrian motifs intermingled.

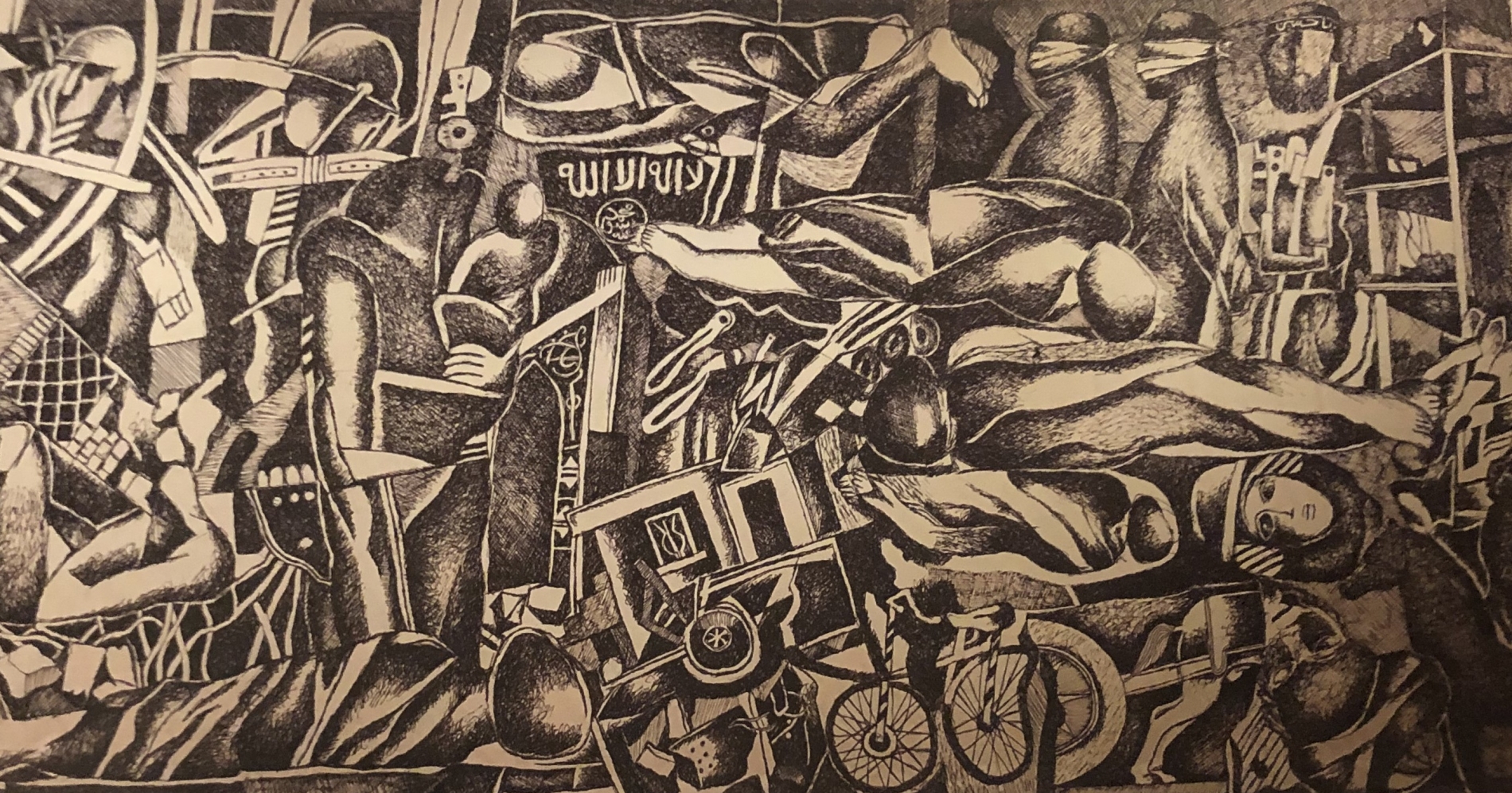

Ruin also features in the mural of Mosul. Titled Panorama of Destruction and rendered in charcoal black upon white canvas, it depicts the devastation of Islamic State (IS) rule. With feverish imagination, al-Azzawi has scattered dismembered limbs, torn torsos, severed blindfolded heads, skulls, and a single female face crowned by what seemed half-helmet, half-headscarf. Stones, knives, keys, tools, and fragments all merge into an infernal, subterranean world of the dead, alongside the IS flag and the name of al-Nuri Mosque, inscribed in reverse. This is where IS leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi declared the so-called Islamic Caliphate.

Invoking a curse

Circling the clay installations of Mosul and Aleppo, it is hard to escape the sense that Azzawi is invoking a curse—one that befell countless cities, including Basra, Baghdad, Mosul, Ramadi, Hama, Homs, Aleppo, Raqqa, Daraa, Sweida, and beyond, to Mount Hermon (Jabal al-Sheikh) on the Lebanese-Syrian border, and even Yemen’s capital Sana’a, or its port city of Hodeidah. The genocide in Gaza seemed to cast its shadow over al-Azzawi’s entire panorama.

Never in the post-1945 world order have governments been so silent in the face of extermination as they have in relation to Gaza since October 2023. What a contrast to the global outcry that followed the 1982 Sabra and Shatila massacre in Beirut, perpetrated against Palestinians under the protection of Israeli commander (and later, its prime minister) Ariel Sharon during Israel’s invasion of Lebanon.

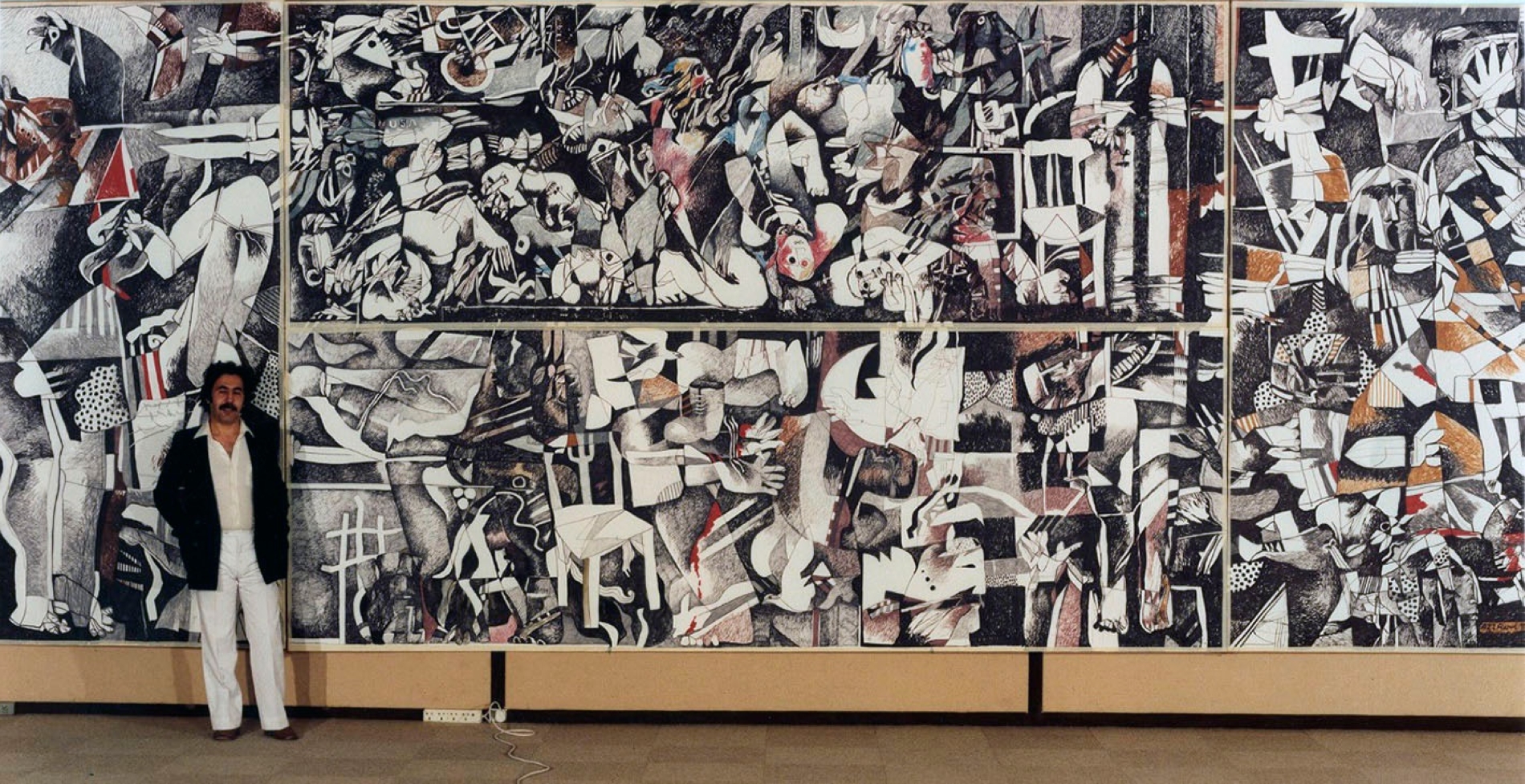

Al-Azzawi immortalised that massacre in a monumental mural that became one of his most celebrated works worldwide. He drew from the images he saw in London and from the writings of French author Jean Genet, who visited Beirut in the summer of 1982 and then published his searing account, Four Hours in Shatila.

Al-Azzawi later echoed Genet’s haunting words, saying: “I had to go to Shatila to understand the obscenity of love and the obscenity of death. For in both, bodies have nothing to hide... A man lay face down, his body swollen and purple-black... The wound on his thigh—was it from a spear, a knife, an axe, or a dagger? Flies hovered over it. His head was larger than a watermelon, a black watermelon... I asked his name. ‘A Palestinian,’ a Frenchman answered. ‘Look,’ he said, ‘look what they did.’”

False witnesses

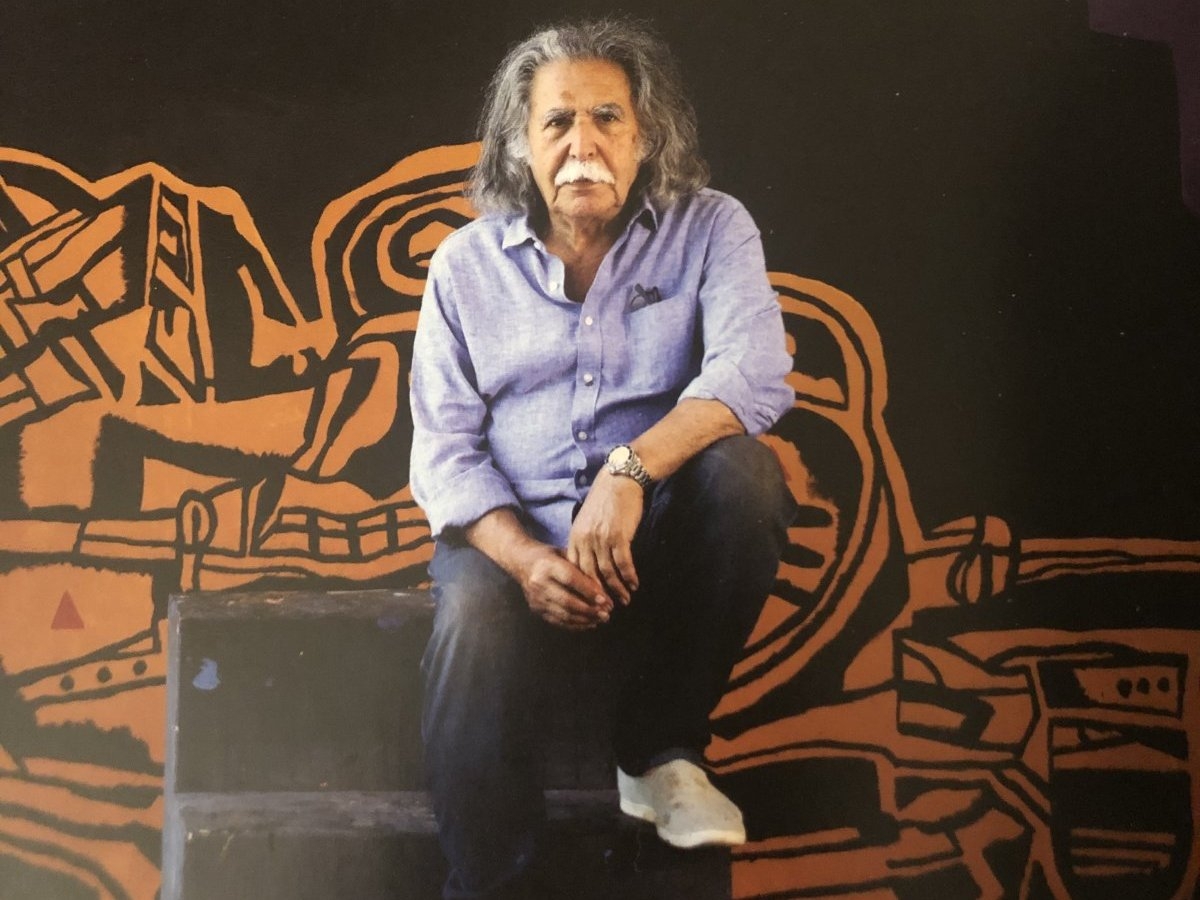

Al-Azzawi, who fled Iraq under Saddam Hussein’s dictatorship, titled his Beirut exhibition False Witnesses. He said: “I lived in another Iraq—that of the 1950s and 60s. I don’t want to be a false witness. One does not live twice. I will not return to or visit Iraq. Many who did after the tyrant’s fall soon left again for exile. I wish I had left earlier.” To see his work in Beirut, one would think he never left Iraq. Yet distance seems to have let him immerse himself more deeply in the country: intellectually, emotionally, and spiritually, exploring its civilisational and cultural legacy.

His features appear resolute, his expression grave, like a figure drawn from one of Mesopotamia's ancient epics, or from a poem by Iraqi poet Yusuf al-Sayegh, who once wrote: "My bones rattle like the bones of hyenas." Earlier in his career, al-Azzawi transformed several of al-Sayegh's poems into painted forms. Since the 1970s, poetry has been a defining influence in his art—the verses of Mahmoud Darwish, Adonis, Mohammed Mahdi al-Jawahiri, and Mudhaffar al-Nawwab—but al-Sayegh holds a special, personal resonance.

Al-Azzawi's paintings, murals, and sculptural installations depict Iraq's tragedies in the aftermath of Saddam Hussein's tyranny and the American liberation/invasion that pulverised and fragmented the country. This, in turn, gave rise to Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi's IS and the Iran-backed Popular Mobilisation Forces (PMF). Before that, the Arab defeat of June 1967 marked a turning point in al-Azzawi's art, shaping his later engagement with political struggle, most vividly through his depictions of Palestinian resistance in Jordan and Lebanon.