Since last June, Lebanon’s skies have witnessed a strange, though not unprecedented, convergence of war and art. Social media platforms have circulated footage of Lebanese citizens undeterred by the Iran-Israel war, persisting in their revelry of song and dance.

Had a composer sought inspiration from the fiery, smoke-laden spectacle that dominated Lebanon’s skies for days, they might have produced a rare piece titled Dance of Fire. Its spiralling rhythms would trace the ballistic trajectories of missiles, now descending toward Haifa or Tel Aviv, arriving from western Iran. It would resemble a composition in a warlike maqam, drawing horizontal lines to the edge of the sky, ascending into space, then plunging to southern altitudes where it meets other trajectories or detonates prematurely, scattering sparks that touch the soul.

Meanwhile, the indifferent, or perhaps those schooled in dark realism, continue their dance. The Lebanese, long exhausted by conflict, call it the ‘rebirth of the phoenix,’ a recurring homage to their ancient, once-glorious and now-vanished civilisation.

The image of dancing beneath missiles evokes the most extreme existential nihilist motifs seen in cinema, from the aftermath of World War II through the Cold War to the great invasions and wars at the close of the last century. Over the past quarter-century, such scenes have inspired filmmakers beyond the US as well as content creators on digital platforms. This strand of nihilism, fuelling absurd yet deliberate behaviour, is woven into Lebanon’s long history: a nation besieged by the narrative of war, deprived of security, yet clinging to survival against all odds.

Reviving ancient theory

Faced with this bleakness, a diverse group of contemporary musicians from across Lebanon’s cultural landscape has chosen to operate on a different artistic and existential plane. They have moved beyond the exhausting pursuit of analysis, anticipation, and conscious understanding. Instead, they have found answers in primal musical forms: sonic experiments and hypnotic performances that speak to raw instincts, centred on the search for safety amid the ever-present threat of death.

This trend recalls the avant-garde musical movements that emerged after World War II, where lyrics were minimised in favour of heightened vocal and kinetic expression. These forms served both as a protest against political and cultural systems that had weaponised language in propagandistic rhetoric, and as an assertion of the desire to rebuild and transform. Meredith Monk, born in 1942 and to be honoured this October with the Venice Biennale Musica Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement Award, was a pioneer of this approach in 1960s New York. Her vocal compositions rarely feature recognisable text, reflecting her sustained search to reconcile two seemingly opposing ideas: a primal voice that speaks to the future.

A similar impulse is at work in Beirut’s music scene, where certain producers seek to break decisively from the clichéd image of the ‘city that dances through anything.’ In its place, they chart a liberated creative path toward a primordial human essence, earthly or subterranean, authentic and untamed, where strength and sorrow intertwine. This is a clear rebuke to the romanticisation of Lebanon’s tragedy—the fashionable treatment that blends rustic nostalgia with a contrived modernity.

This strand of primal music is one of three distinct currents shaping Lebanon’s alternative music scene. Alongside it runs a second, more familiar current—ethereal music—deeply rooted in the region’s geography and spiritual heritage. One of its notable branches is contemporary Sufi music, which seeks to ‘purify souls from the debris of cruelty and futility born of an inescapable alliance between the machinery of war, economic collapse and systemic corruption.’ The third current, with unmistakably Asian roots, unfolds within a shamanic framework that calls for a return to nature as a place of refuge and healing.

Within these three movements, performers and musicians such as Faten El-Khechen and Veer Selas of the Ashira Tribe Band, Tarek Bashasha of the Tajalli Band, and Daniel Balabane, with his Indian collaborator Shati Sukla, are each working within their own spaces and creative visions to infuse Beirut with peace, abundance, and joy. Their ambition is to raise the city's 'energetic vibrations,' reviving spiritual and mystical traditions long obscured by the fog of conflict and the haze of pollution.

"We seek to accompany people on a journey of ecstasy," says Bashasha, a theatre artist and co-founder of the Tajalli Band. "Through the melodies of our instruments, we reweave the city's tapestry, transforming it into a carpet upon which we dance." For more than two decades, the band has sought to revive the emotions and ideas of Sufi poets such as al-Hallaj, Ibn al-Farid and Rabia al-Adawiyya, as well as the musical traditions of 19th-century Aleppo. All set to the rhythms of clarinet and guitar.

Members of the Ashira Tribe Band, meanwhile, seek to send healing vibrations into the ears of their audiences in Ras Beirut and Achrafieh, bridging the capital's western and eastern quarters. They draw on instruments once played by Indigenous peoples of South America and Australia, including the didgeridoo and the rain stick, evoking an ancient sonic language of restoration. At the same time, melodies from northern India carry Hindu meditative sensibilities into Beirut's storied Hamra Street.

Music behind closed doors

Yet for all their experimentation and spiritual resonance, these projects have yet to rival the dominance of mainstream pop culture, which continues to flourish, improbably, much like the city's inflated real estate market and the soaring fees of its privatised beaches. Alternative performances often remain within studios or enclosed venues, a necessity born of insecurity and the caution of organisers since 2019, the year that marked the beginning of Lebanon's most acute collective collapse in modern history.

"With the Covid-19 pandemic, the October Revolution, the economic collapse, the port explosion, and the Israeli aggression that has continued since the summer of 2024 alongside regional wars, a new reality has taken hold in Lebanon's alternative music scene," says Michele Paulikevitch, an activist and long-time cultural programmer. "Concerts have withdrawn behind walls, retreating from public squares. The boldness with which we once organised open performances in shared spaces after the civil war has given way to profound caution."

Charlotte Aillet, cultural attaché at the French Institute of Lebanon, echoes these concerns. She notes that while the centre celebrated the talents of 150 Lebanese musicians during June's Fête de la Musique, it was forced to cancel the participation of two visiting French groups due to "airspace closures and uncertainty over security developments."

Journeys into the realm of meaning

In the musical world of the Tajalli Band, Bashasha and his fellow musicians lead their audience through alternating currents of conscious and subconscious perception, swaying between surrender and initiative. The programme, at once carefully composed and open to improvisation, unfolds as a textured sonic journey.

Its melodies shift fluidly—from the hypnotic pull of collective instrumentation to the mystical incantation of al-Hallaj. Then comes the haunting tā'iyya of al-Farid, whose verses, with their celebrated couplets, carry the audience deeper into the spiritual journey. The journey builds toward contemporary spiritual visions evoking Marrakech or Nicosia, before closing with al-Hallaj.

By the end, the audience—having travelled from Beirut, Saida, Byblos, and Batroun to the banks of the Tigris, the wilds of India, the Kazakh steppes, and the taverns of Seville—is transported. "This migration draws us away from cruelty into union with our essence. What Lebanon needs most now is to reconnect wholly with our inner worlds, long neglected until love withered within them," Bashasha tells Al Majalla, flanked by his children, who share his musical passion. He is quick to stress Lebanon's historic defiance of typecasting: "We are not a traditional Sufi chanting ensemble. Our electric and wind instruments include no ney, for example. We evoke ecstasy through melody and sonic progression, not through the symbolism of any single instrument."

On another creative 'planet,' named for the trinity of immortality, light, and the resonance of the spoken word, sound blurs the boundaries between the celestial and the earthly, the divine and the nihilistic, the human and the animal, pain and rapture. Here, the artist's own body becomes the instrument, sending waves of energy in shifting vibrational frequencies.

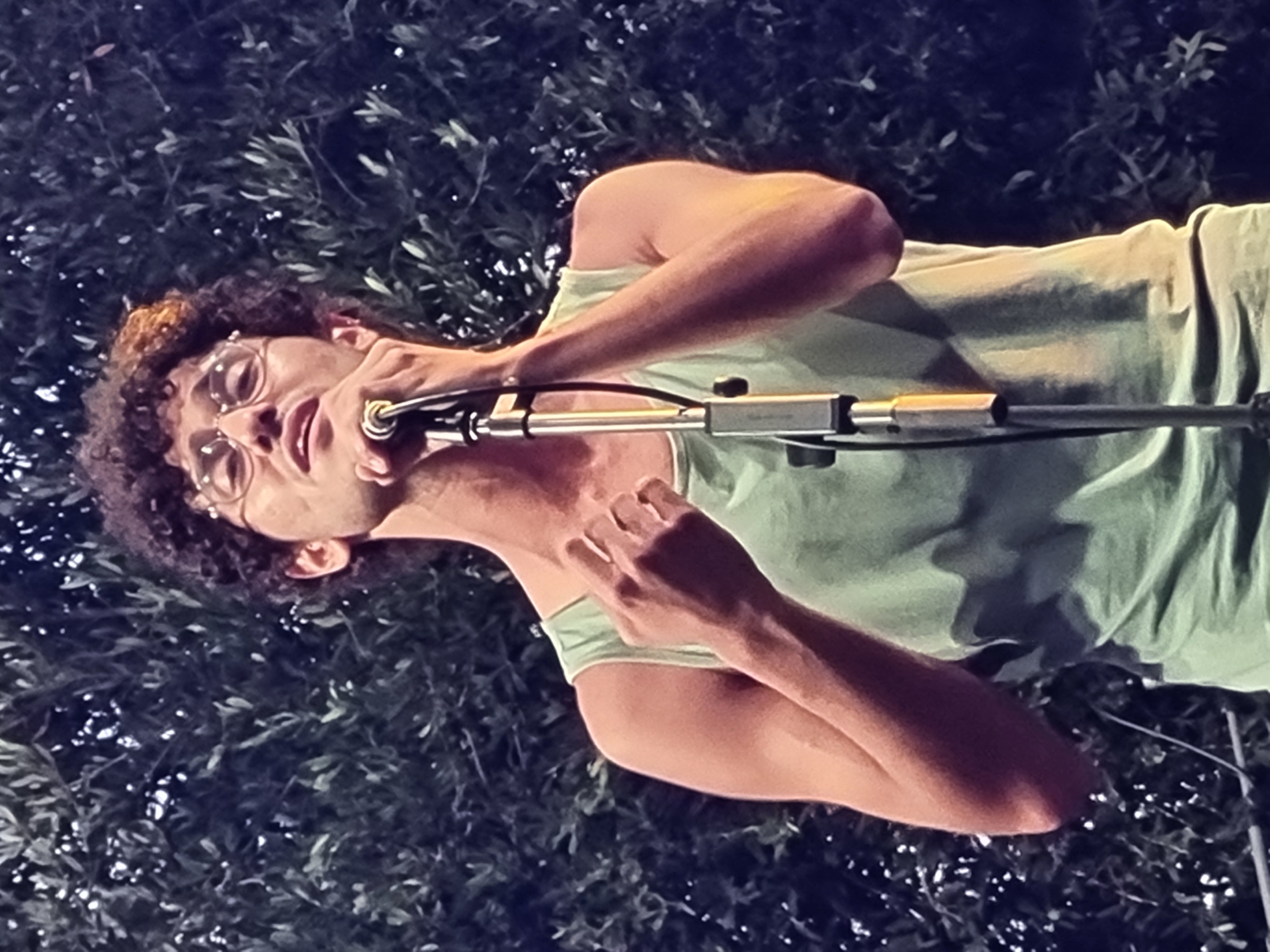

In this realm, a 20-something from Byblos, who adopted the name Veer Selas during what he calls a "spiritual awakening", takes the stage with a rain stick—a hollow staff filled with dried seeds and pebbles whose rattle evokes a sudden downpour. In the garden of the National Library, the audience is drawn into his trance-like state.

Yet the rain stick is incidental. The real instrument is his flesh and breath—the body as a vessel of sound. At times, it channels earth-rooted tribal song; guttural cries that declare: "Here we are, capable, resisting, acting." At others, it summons luminous hymns and temple chants, or dissolves into whispers—"a dance at the threshold of breath," as he describes it—testing form and resonance.

"This ritual music first carries me inward, into myself as a complete, undiscovered land," says Veer Selas. "A land of consciousness that becomes a medium for receiving deeply rooted messages, which I hold fast even as I soar beyond the limits of focus."

He calls this state al-sarha—the trance. "In Beirut, I learned to free myself from fear's grip and wander toward discovery," says the artist, who began composing at 12 and draws inspiration from Norwegian singer Aurora and contemporary Scandinavian folk revivalists. "I belong to a generation of 'streamers'—not singers or musicians in the traditional sense, but performers who broadcast their own music, on stage or online. We speak directly to audiences, turning our bodies into conduits of energy, exploring their limits to produce raw sound. I do this as an act of defiance against despair."

Stockhausen's cave

Is this streamer from Byblos living in denial of a harsh reality? "Perhaps," he replies with a luminous smile, his eyes steady on his interlocutor, as befits the courage of a young man composing a fresh and daring narrative built more on possibility than the permanence of security.

Unlike the entrenched world of mainstream pop, which enjoys a relative immunity sustained by public taste and commercial forces, streamers embrace the risks of choosing alternative creative lives. In doing so, they follow a lineage: rappers, rockers, death metal artists, jazz musicians, electroacoustic composers, and free improvisers who forged local and global sounds, rhythms, and noise to express their bond with their surroundings and the wider world.

These pioneers challenged the classical modes that preceded them, only to establish new forms of pop that, in turn, may now be ripe for dismantling or reinvention—a process described by European sociologists Anthony Giddens, Ulrich Beck, and Scott Lash as 'reflexive modernity,' a deconstructive rebuilding.

There was, however, a fourth European thinker of equal weight, working at the intersection of sociology and music. In the late 1960s, at 40 years old, he arrived in Lebanon on the cusp of turning the country into an international platform for his bold intellectual 'rocket': a 'musical revolution' grounded in spiritual and socialist currents. History, with a twist of irony, would remember him instead as the founding father of electronic music—the German composer Karlheinz Stockhausen.

His 1969 composition Jeita, written to mark the partial opening of the cave's upper chamber, became a vehicle for furthering his early explorations into experimental sound. The work employed tone rows—ordered sequences used to generate melodic material—ensuring no note was repeated and producing an abstract musical texture. The cave, where life seemed to breathe and unfold with the slowness of a tortoise, enabled him to develop his technique of 'point sound,' in which isolated tones were projected into space. Blended with elements of controlled aleatoricism—chance harnessed within rigorous boundaries—the result was a soundscape of shifting rhythmic patterns and spatial distribution, continually in flux, alive with vitality and motion.

Through these early experiments in spatial sound, which transformed music into a three-dimensional experience, Stockhausen became a pioneer of what is now called 'immersive art' within sound practice. His musical revolution also embodied globalisation and cultural transcendence. By fusing innovation, technology, and sensory exploration, he sought to redefine music as a universal language of communication—one that could transcend cultural and geographical boundaries through the ordering of sound in space.

In June, the explorations of Khechen, a Lebanese artist who performed on a two-metre-long wooden horn during Beirut's Fête de la Musique, coincided with a commemorative return of Stockhausen to the city. Nearly half a century after his first visit, his legacy was celebrated through the screening of a documentary on one of his monumental operas, Licht (Light), at the Beirut Art Film Festival.

The life and death of a white ant

Armed with ancient musical knowledge—some drawn from the traditions of Indigenous Australian peoples—and adorned with tattoos and primal ornaments, Khechen approaches the didgeridoo with deep, measured breaths and lips trained to quiver along its mouthpiece. Her connection to the instrument embodies a narrative of death and rebirth in all its manifestations.

It begins with the white ant, invading the dead wood of eucalyptus or bamboo, burrowing and gnawing until the hollow is left behind, where it lays its larvae—proof that life can spring from decay. It continues with the profound rapture of breath, which Khechen believes transforms her into a conduit, "summoning ancestral energies to heal the living," as she tells Al Majalla. It culminates in the ancestral stories of the Māori, Gadigal, and Palawa tribes, who fashioned the instrument from hollowed trunks, polished and tattooed them—much like the markings on the musician's own body—and released their music into the world.

Here lies an endless cycle of destruction and renewal, an "eternal labyrinth," as Stockhausen once described his opera Licht, or perhaps the destiny of Beirut itself. "I blow as if I were a child spitting in the face of that nihilistic state—at once terrifying and exhilarating—of living and creating music in Beirut," Khechen says. "I turn my body into an extension of the instrument, much like Veer Selas's transformations, joining with the tube to become a channel that carries healing energies from ancient, collective experiences into the present moment."

Her fusion with the long wooden wind instrument—blending emotion with vibrating sound—also evokes an earlier experiment by another Lebanese artist, Mazen Kerbaj, whose multimedia work marked a new phase of artistic exploration two decades ago.