After more than a decade of war, Syria’s energy sector lies in ruins—but the scramble to rebuild it is already underway. With former Syrian President Bashar al-Assad gone, oil and gas attention is returning fast, but so is a quiet, grassroots solar revolution. The country now sits at an energy crossroads: will its recovery be anchored in oil and gas, or will it seize the chance to lean into renewables and build something more resilient?

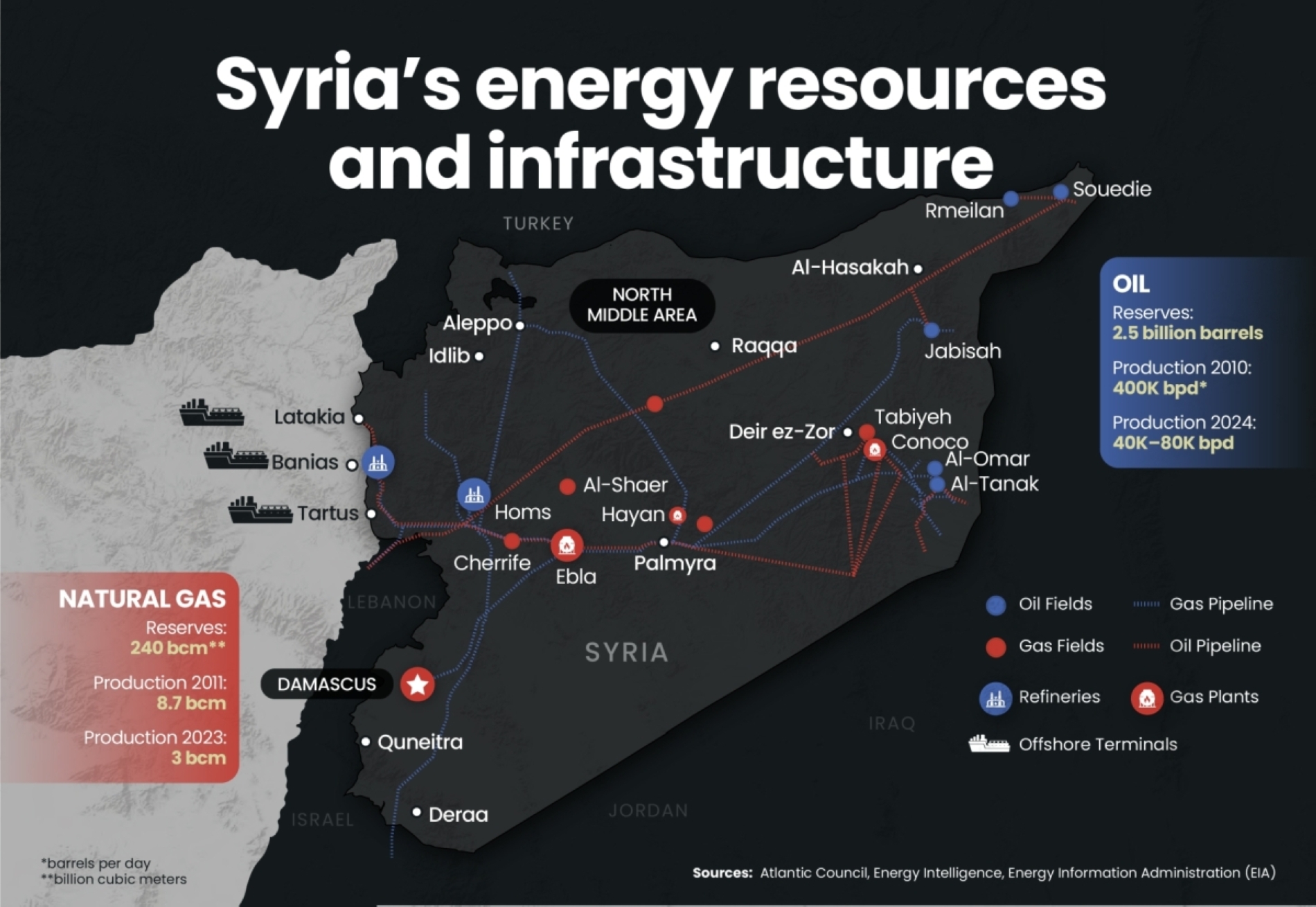

The Syrian civil war destroyed Syria’s conventional energy infrastructure and has fundamentally weakened the country’s capacity to extract, refine, and distribute fossil fuels. Before the conflict, Syria’s oil and gas sectors were key pillars of the national economy and major sources of state revenue. But the war triggered a dramatic decline in capacity. Electrical generation capacity plummeted from 9.5 gigawatts to just 1.6 gigawatts, while infrastructure losses in the electricity sector alone are estimated at $40bn.

The geopolitical advantages Syria once derived from its position as a regional energy hub have also been severely eroded by territorial fragmentation and instability, making it difficult to restore secure energy corridors or attract external investment. Restoring Syria’s role in regional energy flows now hinges on the long-term prospects of security, economic stabilisation, and physical reconstruction—none of which are guaranteed.

Syria’s new authorities have prioritised rebuilding the sector. The new Ministry of Energy was formed in March as a result of the merger of the Ministries of Electricity, Oil and Mineral Resources, and Water Resources.

It will take time for the new authorities to establish a functioning national energy regulator capable of managing energy policy, managing the reconstruction of Syria’s energy production infrastructure, and overseeing the surge of interested foreign investors exploring opportunities in Syria’s energy sector. Rebuilding physical assets, one of the first steps, is only half the battle. Rebuilding the governance architecture to manage and equitably distribute energy resources is just as urgent.

Before the fall, the Assad regime relied almost entirely on imported fuel from Iran, smuggled oil sold by non-state actors across conflict lines, and solar energy to keep the lights on. Without access to Syria’s eastern oil fields, al-Assad looked to build a national renewable energy strategy to address mounting electricity shortages.

In 2024, the Assad government announced its intention to develop 2,500 MW of solar power and 1,500 MW of wind by 2030, and claimed around 100 MW of solar capacity had already been connected to the national grid. Al-Assad’s energy minister sought support from “friendly countries” like China to back new projects, including a prospective 200 MW wind farm in Homs and other wind-rich areas. However, the strategy remained largely aspirational due to financial constraints and fragmented governance.

Fossil fuels or renewables?

Al-Assad is now gone, but Syria’s energy crisis remains. The country’s most valuable energy assets remain divided. While Syria's eastern oil fields were long held by Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), a May 2025 agreement between Syrian authorities and SDF leadership transferred control of several key fields back to the central government.

This shift opened the door to a series of new energy deals aimed at reviving the country’s fossil fuel sector. In May, a Qatar-led consortium announced a $7bn energy package to provide an estimated 4,000 MW of gas-generated power and 1,000 MW of solar capacity. It was followed later by a Qatar-backed plan to supply Azerbaijani fuel to improve electricity output in northern Syria.

Meanwhile, Syria is also exploring a potential joint venture with major US energy companies—tentatively named SyriUS Energy—to rehabilitate its oil and gas infrastructure and ensure affordable energy access. Under this proposal, Syria would hold a 30% stake through a sovereign energy fund.

These deals signal that fossil fuels will continue to dominate Syria’s reconstruction agenda; however, the inclusion of solar energy in the Qatar agreement introduces a notable shift. For now, such hybrid arrangements appear to be the exception rather than the rule. Syrian policymakers must avoid prioritising the quick fixes—overreliance on fossil fuels—over long-term sustainability.

Syria's geography continues to entice regional powers eager to reshape energy flows. If stability returns, the country could again serve as a key corridor linking producers to European markets. Türkiye has proposed extending the Arab Gas Pipeline through western Syria to offer an alternative to LNG shipping routes and challenge the Eastern Mediterranean Gas Forum, a regional energy alliance that includes Egypt, Israel, Greece, and Cyprus.

Yet such overlapping ambitions risk turning Syria into a race for external influence. This could result in energy transit routes being shaped more by strategic competition than by coherent development or energy diversification strategies.

At the same time, energy access within Syria remains deeply unequal. While some urban households and business owners have been able to install solar panels or invest in backup systems, many rural communities, displaced populations, and informal settlements remain locked out of these gains. For millions, daily life is still defined by diesel generators and unreliable power—contributing to pollution and fuel dependency. Unless energy recovery plans explicitly prioritise marginalised communities, they risk deepening existing inequalities and reinforcing the same fault lines that fueled the conflict.

Energy master plan

In May 2025, the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) and the Government of Norway introduced a Renewable Energy Master Plan to guide Syria's energy recovery. Over the next year, the plan will assess the country's future energy needs, determine how much can realistically be generated from renewables such as solar and wind, and recommend legal and policy reforms to facilitate a clean energy transition.

The plan lays out 12 priority areas, including expanding electricity access, reducing fuel imports, creating clean energy jobs, and avoiding wasted investment in outdated infrastructure. It also provides guidance for integrating renewables into the existing power grid and introduces progress-tracking benchmarks. UNDP is also working with local institutions and universities to train a new generation of renewable energy professionals.

While the challenges are steep, Syria's bottom-up energy shift offers a rare advantage. Rather than waiting to rebuild the central grid, Syria could capitalise on these systems to pilot adaptive, low-cost technologies tailored to fragile environments—models that may hold lessons for other conflict-affected nations. Years of grid failure and wartime destruction have forced many households and businesses to turn to solar panels for power—creating a grassroots renewable base rarely seen in other post-conflict countries.

Though limited by economic hardship, this improvised infrastructure has laid the foundation for a decentralised energy model. Small-scale projects, privately funded or by NGOs, helped establish an ecosystem of decentralised, household-level solar units. For example, in Northwest Syria, informal networks of solar panel installers, battery sellers, and repair technicians have built a fragile but functional ecosystem.

While not formally regulated, this local clean energy market has proven adaptable and innovative under wartime conditions. Supporting these actors—through training, microfinance, or integration into formal recovery programs—could strengthen Syria's renewable transition from the ground up and ensure that recovery is not solely foreign-led.

A recovery anchored to fossil fuels?

Decarbonisation in post-conflict contexts is difficult. Governments emerging from war often face urgent fiscal demands, limited institutional capacity, and intense political pressure to restore basic services—conditions that favour fast, familiar fossil fuel solutions over slower, capital-intensive renewable alternatives.

For Syria, where governance remains fragile and access to financing is constrained, the transition to clean energy may be a long-term aspiration for local authorities rather than an immediate priority. The fossil fuel sector still dominates Syria's economic reality.