The ceasefire agreement in Lebanon was reached on 27 November 2024, yet the process of implementing UN Resolution 1701 is still underway and continues to face obstacles and challenges.

The new president and government made clear that their strategic objective is to uphold the principle that arms should be held exclusively by the government, meaning disarming Hezbollah and the Palestinian factions in the refugee camps.

This places the Lebanese state at a historic crossroads. While they have clarified their preference to achieve this goal through dialogue with Hezbollah, it is hard to believe that it can be accomplished solely through peaceful means. This is particularly so when Iran provides clear and public backing for Hezbollah’s refusal to comply.

On the ground, the Lebanese army is demonstrating assertive activity in southern Lebanon in a way not seen before. For its part, Israel has not yet completed a full withdrawal from Lebanon. Before doing so, it wants to ensure the Lebanese army’s control over the territory and to maintain pressure on the Lebanese government to implement and expand the disarmament of Hezbollah.

The Lebanese state and society—rooted in the trauma of the civil war—fears sliding back into such conflict, which is understandable. But many also see this as an opportunity that can't be missed, and if not seized now, may not occur at all.

A masked ultimatum

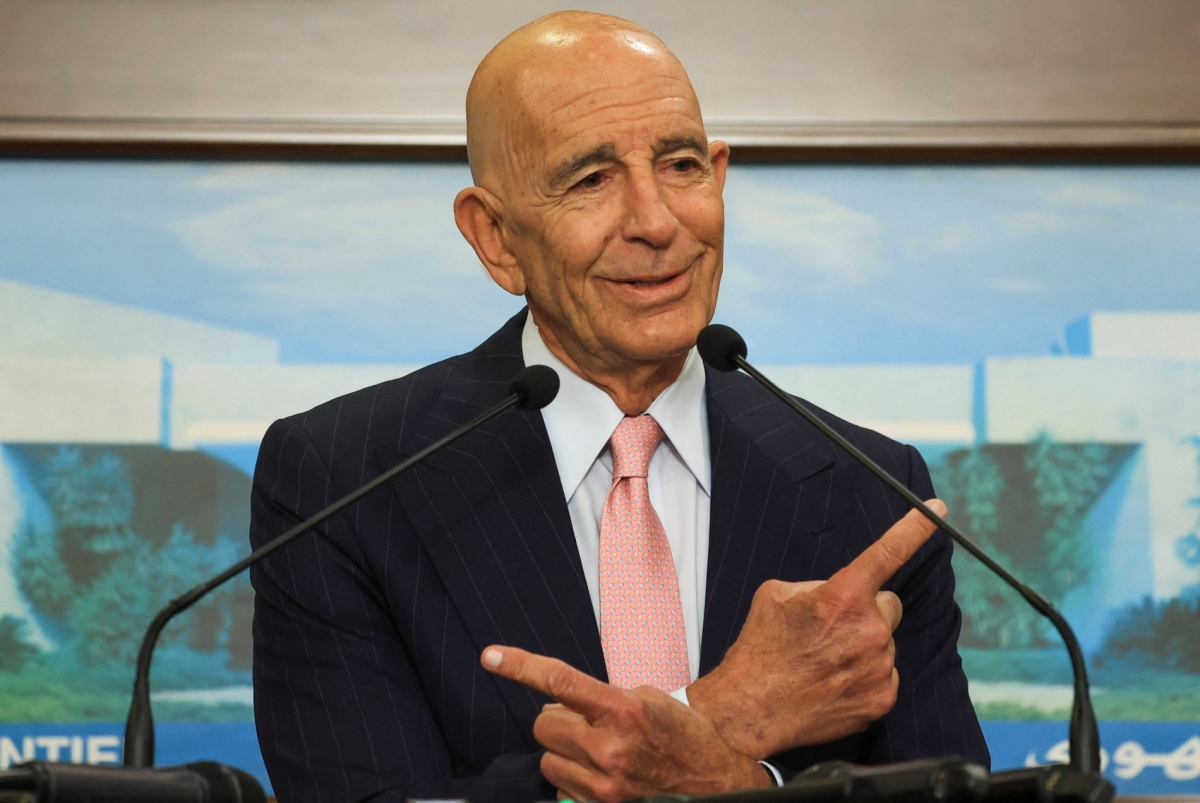

US special envoy to Syria Tom Barrack used his latest visit to Beirut to deliver what was, in effect, an ultimatum to the Lebanese government, though he took care not to present it as such. The substance of his remarks made it clear where Washington stands. The Lebanese media widely reported the main points of his overall message, which can be summarised as follows:

A. Lebanon is not high on the priority list of the main regional and international actors. The international arena expects Lebanon to implement its commitment to disarm Hezbollah.

B. Syria is now at the top of the Middle East agenda. The regional struggle centres around it, and there is greater interest in channelling funds to rebuild the Syrian arena. In this regard, Lebanon is a secondary front.

C. The United States will not pressure Israel to soften its stance—particularly on the disarmament of Hezbollah. For its part, Israel has no confidence in the United Nations and its institutions, and therefore sees no need for UNIFIL, which has failed to oversee the implementation of Resolution 1701.

The US administration has drastically reduced its contribution to the funding of UN peacekeeping forces, and therefore, it is uncertain whether UNIFIL’s mandate will be renewed, or alternatively, whether its troop numbers will be cut dramatically to just a small number of observers. Implicitly, the US may support Israel’s preference to abolish UNIFIL’s role altogether.

High risk, high reward

Barrack’s blunt message was aimed at turning up the pressure on the Lebanese government to deliver on its obligations. The move is not without risks, but the timing is highly favourable: Iran and Hezbollah are significantly weakened, the Assad regime is gone, and the regional balance of power has shifted in dramatic ways.

Israel is closely monitoring developments in Lebanon. From its standpoint, maintaining military pressure should help the Lebanese government use the “Israeli stick,” as well as the American one, to get on with disarming Hezbollah.

Moreover, one cannot deny that, after 7 October, Israel has fundamentally shifted its security doctrine from restraint toward assertive use of its weight, military power, and the support it receives from the Trump administration, to pressure, and possibly even force its will.

Still, caution is advised, and Israel would be well-advised to recalibrate its approach toward Lebanon in a more sophisticated way, by exercising silence and restraint, and not inserting itself into Lebanon’s internal debate over Hezbollah’s disarmament. Israel’s position is clear enough; there is no need to repeatedly wave the stick.