Over a decade later, I still remember an idyllic scene I once glimpsed from the window of a bus. At the time, I was hurtling towards the Pacific. It was a bright mid-afternoon, and already we had left the chill of the Andes far behind and were crossing a tropical landscape towards Ecuador’s sizzling coast. I had long since fallen into a sort of trance. There was little to arrest the eye.

Suddenly, in the midst of this dreamlike boredom, I was ambushed by desire. A few yards from the side of the road, I saw a girl in a hammock. Beneath her some chickens were pecking in the dust. The hammock must have been slung from the trunks of trees; I didn’t lose time analysing the picture. All I noticed were the chickens, the hammock and the girl, and my desire, which was aroused in an instant, latched onto these three elements.

The girl wasn’t just relaxing on a sunny afternoon, it seemed to me. Unlike the ads for luxury cruises, she wasn’t offering a respite from toil. She was more like an argument for idleness as a way of life. Hammocks, like floating beds, are the closest an earthbound human can get to levitating. Gravity, money, stress and the necessity of work, death, along with more esoteric concerns like original sin, these stand on one side, pointing accusatory fingers, while the hammock swings idly on the other, casually flipping the bird.

The girl’s composure, along with that of the chickens and, most defiantly, the hammock she was swinging in, seemed to mock activity of any kind and scorn the Protestant work ethic. The sheer languor of the scene was capable of retarding the haste of the coach as we sped by, albeit briefly, as if it had extended time and bent it back on itself. Proust would have devoted an entire book to the phenomenon, while Einstein would have explained the effect mathematically, yet when you see relativity actualised like that, you don’t rush to explain or even to celebrate what’s in front of you; instead, it catches at your soul, throwing you into a state of mourning. I would never be able to join her, there, in that halo of ease.

Admittedly, on a less metaphysical level, I fancied her. It was no coincidence that this glimpse of paradise occurred in the middle of an extended period of enforced celibacy, though fortunately for me the term ‘incel’ was yet to be invented and no one was insinuating that I could not be trusted near women. I lived peaceably with several at the time. Men may be beasts, but this one was reared in captivity. Besides, there was a far deeper level to my sadness than the fatberg of wasted sexual instincts clogging up the subterranean passages of my psyche (it had been a long time). The sadness was not only personal, like the effect of tea and madeleine cake on Marcel. This scene was prelapsarian – for a few seconds, a humble portion of Ecuadorian soil had reverted to Eden – so I’m talking about a sense of loss on the scale of the entire species.

This much, then, by way of preamble to a meditation on the hammock. I don’t recall whetherBertrand Russell said anything about hammocks, but if not, then his essay on idleness should be supplemented by a long footnote on the subject, and this is the man to provide it.

At well over four hundred pages,The Falling Skyby Davi Kopenawa certainly qualifies as that footnote. It never explicitly singles out the hammock as a symbol, but many of the book’s remarkable events take place there. Unlike the one in Ecuador, this hammock is suspended from a ceiling, but it is also, belonging as it does to a shaman, suspended from every tree in the forest. Remove the forest and the shaman, along with the sky itself, would promptly fall:

‘…the sun […] who is also a jaguar being, will angrily come down towards the earth and devour the humans like they were smoked monkeys.’

Smoke is the serpent in this paradise. What Kopenawa calls ‘epidemic smoke’ could easily rise and choke the sky’s chest. If the shamans die, the orphaned spirits will cut up the sky in fury. Then the sky will collapse, because there are no longer any shamans to hold it up.

There are times when the cosmology is as dense as one imagines the forest itself to be, but the underlying anxiety is palpable. In fact, this whole miraculous, poetical book is ‘vexed to nightmare’ not by the rocking of Yeats’s cradle, but by the swinging of an insecure hammock and the ever-present fear of falling. Maybe ordinary, less sensitive members of the tribe are able to sleep soundly, but Kopenawa is the kind of man Yeats would have no trouble identifying with. After all, the Irishman had a lifelong fascination with the occult. Like the shaman, he communed with the spirit world and sensed the onset of the apocalypse.

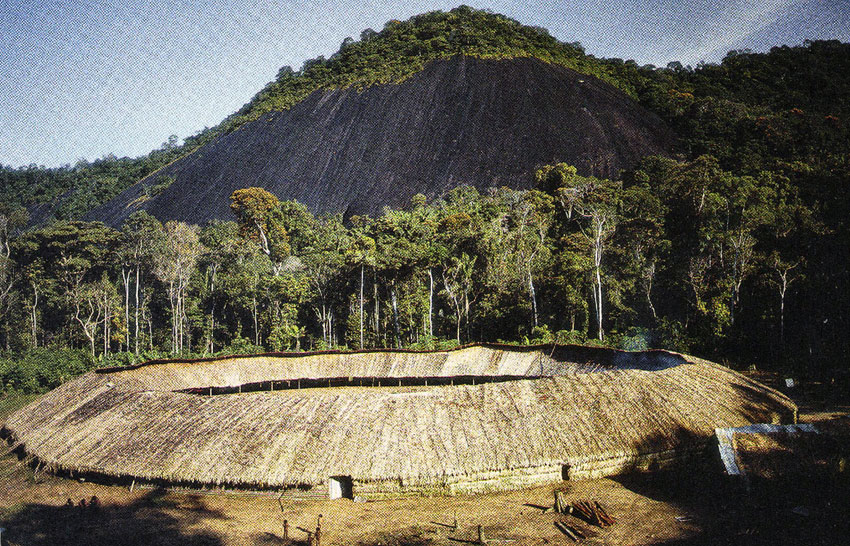

Kopenawa’s tribe resides in a big communal house in the forests of northern Brazil, near the border with Venezuela. Sleeping in hammocks slung from the roof, they have managed to preserve the habits of millennia that existed long before Columbus. Hammocks are an essential part of that lifestyle. When a woman decides to take a husband, she ties her hammock from the roof next to his. When a shaman succeeds in attracting the ‘xapiri’ [pronounced shapiri] or spirits down to dance for him, they take up residence in spirit houses where they sleep, naturally enough, in hammocks.

As a child, Kopenawa had great difficulty sleeping. He would toss and turn, frightened of the intimations from the spirit world. It was only as he grew that he began to realise these were attempts by that world to communicate with him. It was his father-in-law, a great shaman, who first blew the powder of the yakoanaplant into his nose that would enable Kopenawa, after great struggle and even terror, to become accustomed to the company of spirits, to become ‘other’ and ‘like a ghost’ in order to cease living like ordinary mortals and make a journey (or his image, at least) to the chest of the sky, far above the forest. Eventually he was able to attract spirits down to sing and dance for him, but not without going through severe privations.

The shaman has to renounce sex, for example. Spirits dislike the smell of penis, apparently. This comes as no surprise. After all, there had to be some good explanation for the fragrant Gwyneth Paltrow’s reluctance to extend her range into the next available genitals. More precisely, there must be no ‘eating of vulva’ as the translator puts it, in what is really the closest to a description of cannibalism the book has to offer. There’s a lot of this vulva-eating going on, but notif you’re an aspiring shaman.

The novice must also forgo meat. If he hunts game, such as tapirs, he has to wear the correct adornments and stalk his quarry with infinite patience, but for all his exertions he must never eat the animals he manages to kill.

Given these privations, it’s hardly surprising that the youthful Davi Kopenawa was fit for little more than lying in his hammock for days on end, getting physically weaker and closer to the spirit state. He dreamt a lot. At last, the reward for his self-control was the uncanny beauty of the spirits who sought him out in their droves. These spirits were ancestral. They moved balletically, sang like sirens and were so perfect that even their farts smelt sweet. Word to the wise, Gwyneth. They were the emanations of the forest and of its creator, Omama, and ordinary tribesmen just didn’t know what they were missing.

Without leaving his hammock, Davi was then able to travel to the back of the sky and meet the ghosts of his ancestors there. He was taught by his xapiri the ways of curing people’s ailments. With time he could attract great numbers of spirits into his spirit house, and, unsurprisingly, he had no desire for material possessions. His mind was on higher things.

The book contains long meditations on the ethereal realm of the forest and on the only root of virtue in men: boundless generosity. Most of the members of the tribe make haste to give stuff away the moment they acquire it. Like two friends bickering over who pays the bill, people strive to outdo each other in their munificence. A good man dies without a stick of furniture to his name, having successfully disposed of everything along the way, and is mourned by the entire tribe for weeks on end. It’s easy to detect the echoes here of the noble cannibals described by Montaigne.

Stepping out from the rhythm and the mores of life in the forest is, therefore, as one might expect, a huge shock, and no one can accuse Kopenawa of half measures. When he ventures beyond Brazil, it is to frenzied megapoliseswhere he sees the destitution in which many of the inhabitants are forced to live. Here, for instance, is his account of New York:

‘…while the houses in the centre of the city are tall and beautiful, those on its edges are in ruins. The people there have no food and their clothes are dirty and torn. They looked at me with sad eyes. These white men are greedy and do not take care of those among them who have nothing. How can they think they are so smart? They do not want to know anything about these needy people. They reject them, and let them suffer alone. They are happy to keep their distance and call them “the poor”. They even take their crumbling houses from them and force them to camp outside in the rain with their children. It scared me to see such a thing.’

One thinks here of the cannibal of five hundred years ago, astonished at the appalling treatment of our ‘necessitous halves’ (see Of Cannibals, Part Two):

‘Their cities are full of big houses and innumerable possessions, but their elders never give them to anyone. If they were really great men, should they not tell themselves that it would be wise to distribute them all before they make so many more? Do we ever hear the white people say: “Take all the machetes and pots that you see?” We people of the forest possess few things and we are satisfied.’

The sharing of goods in the Brazilian forests before the Portuguese arrived, and a contemporary’s disgust at the very notion of ‘the poor,’ show that things have not altered substantially.

The language of this book is so plaintive and guileless, I couldn’t help thinking of William Blake. At first it seemed like a far-fetched analogy, but then I remembered the film ‘Dead Man’ in which a native American mistakes Johnny Depp for the great poet. Perhaps a genuine ‘savage’ had indeed roamed the chartered streets near where the chartered Thames does flow. It’s certainly true, given the Englishman’s intimacy with the spirit world, that he was some kind of homegrown shaman.

Kopenawa’s attitude to war is equally reminiscent the old mystic poet, who once expelled a belligerent soldier from his garden. His perceived lack of patriotism in a time of war got Blake into trouble with the authorities. Montaigne’s cannibals also come to mind, with their emphasis on valour and lack of interest in the spoils:

‘We do not fight with the same hardness as they do. If one of our people is killed by arrows or sorcery blowpipes, we only respond by trying to kill the enemy who ate him. This is different from the wars with which the white people mistreat each other. They fight in great numbers. They even kill their women and children. They simply make the wars for bad talk, to grab new land for minerals, to tear minerals out of the land.’

This is heartfelt, as the Yanomami are threatened by the depredations of gold miners, ripping holes in the ground, poisoning the rivers with mercury and felling trees to construct their roads.

Like Blake, the shaman’s ultimate aim is to expel men of violence from the garden. Kopenawa consistently associates white people with an inability to dream. The hammock thus becomes a potent image of what we stand to lose, forever, when there are no trees left to hang one from and no dreams worth the name. Of course, there will still be dreamers, just as there will still be trees– even in the streets of Sheffield, if the local council can be persuaded to keep their hands off them – but the forests where the trees constitute the greatest, most diverse biosphere on the planet will be gone, and with them the lifestyle of the tribes who lived there. The world’s soul will be the smaller for it. At this strange and ominous juncture in the geological era known as the Anthropocene, we can still pay heed to the poetic words of a shaman who was born in the forest half a century ago and who has visited the world outside, constantly alert to the poor mental health of its inhabitants:

‘…their thought is short and obscure. It does not succeed in spreading and rising because they prefer to ignore death. They are prey to dizziness […] The white people, they do not dream as far as we do. They sleep a lot but only dream of themselves. Their thought remains blocked, and they slumber like tapirs or turtles.’

The dreams fall short, like exhausted birds. No one dreams with ambition or scope. Again:

‘I can never think calmly in the city. People constantly ask you for money for everything, even to drink and urinate. Everywhere you go you find a multitude of people rushing, although you do not know why. Whenever I stay there too long, I become restless and cannot dream.’

One night in Paris,he sees:

‘a kind of house, very tall and pointy, made of metal like a large antenna covered in vines of sparkling light.’

He takes it to be a spirit tower at first, but is swiftly disabused:

‘As I looked at it, I told myself: “these outsiders do not know the spirits’ words, but they imitated their houses without even realising it!” It baffled me. Yet despite the resemblance, the light from this house of iron seemed lifeless. It was without resonance. If it were alive like a real spirit house, the vibrant songs of its occupants would unceasingly burst out of it.’

Has anyone ever been so disappointed by the Eiffel Tower? There is only one refuge after the confusion and dizziness of his excursions into the white people’s land.

‘I was happy to come back to my hammock […] Yet I had barely settled into it when I was seized by a violent dizzy spell […] I could only keep my eyes set ahead of me, staring like a ghost. Flying to this distant spirits’ land had made me become other, and if the shaman elders […] had not protected me again I might have died of it!’

In his absence, his spirits have been starving, dependent as they are on the powder from the yakoana plant for sustenance, so he consumes it ‘day after day.’ Without the food they would complain, especially the younger ones, and if their ‘father’ disappeared altogether, they would depart. ‘Under no circumstances can we leave them abandoned in their hammocks.’ Dreaming is a sacred duty. It is a measure of the extent to which the philosophy of the hammock is diametrically opposed to the bustle and industry of forlorn Westerners:

‘The lives of white people who hurry like ants seem sad to me. They are always impatient and anxious. They barely sleep, and run all day in a daze. They live without joy and busy themselves with acquiring new merchandise, their minds empty.Once their hair is white, they disappear and the work – which never dies – survives them without end. Then their children continue to do the same thing.’

This perpetual work sounds remarkably like another dream we’ve heard so much about, possibly the most tarnished cliché on the planet. It’s certainly up there with ‘trickle-down economics’ and Disneyland for sheer triteness, but more of that in a second.

Work is spuriously eternal for the Amazonian shaman. His own people have to die, largely because Omama was unable to make them immortal, but also as a result of the ‘cannibalism’ of infectious diseases whose ‘hammocks are made of human skin.’ Yet the forest lives forever. In the land of the white people, individuals also come and go, but work is immortal. From the point of view of the hammock, this apotheosis of work is unutterably bleak and counter-productive. Ordinary tribesmen (not everyone can be a shaman) ‘dream of their children, their garden, visitors to their home, or their wife’s vulva.’ White men have even grown indifferent to that.

‘White people are greedy and make people suffer at work, to extend their cities and accumulate merchandise there. This merchandise is like a fiancée to them. They are really in love with it. They go to sleep thinking about it like we doze off with the nostalgia of a beautiful woman. They dream of their car, their house, their money.’

And they say romance is dead. Elsewhere he claims ‘They sleep without dreams like axes abandoned on the floor of a house.’ Whether they dream or not, these people, most of whom have never been near a hammock, are oblivious to spirits altogether. Could this be the American Dream, the one that has loosed upon the world an epidemic of consumerism?

I may be unconventional in this, but if my own dream world was how Kopenawa describes it, sheer boredom would wake me up. I would actually be too bored to sleep. Anyone whose oneiric life was that dull may as well renounce dreaming altogether and opt for concussion. Given that dreaming is a licence to have and to do whatever you please, one is bound to ask what self-respecting dreamer would have come up with such a humdrum dream in the first place?

Well, we all know the story. Immigrants fled the Old World to embrace the opportunity the dream offered them. They were impoverished, for the most part, arriving on coffin ships with few possessions, from backwaters of grinding poverty where there was no opportunity for hard-working people to prosper. By this account, the dream was not shameless propaganda used to bamboozle the masses into working for ‘the man.’ It was the antidote to poverty and injustice. Only an unamerican ‘libtard’ would assert that it was also the product of an impoverished imagination.

With origins like this, it is no surprise the dream promises a variety of goodies, whether it’s possessions the dreamer is after, or success, though it’s unclear what success would be, exactly, if it didn’t include possessions. And, thereafter, still more possessions, multiplied to infinity. In the words of John Cooper Clarke (a drug-addled shaman if ever there was one), ‘Too much is not enough now, let’s not be naive.’

But this palatable formulation of the American Dream, as prosperity for every law-abiding, hard-working American, has become increasingly improbable. George Carlin famously observed it was called a ‘dream’ because you’d have to be asleep to believe it. Based on unbridled competition, the dream dictates that for every winner there have to be losers. This means that the dream of wealth one day trickling down to the poor is a category error. Peak dream will be achieved when two billionaires battle it out for the presidency, one of them representing the realistic aspirations of the poor – good luck with that! – and the other their false consciousness. For the sake of maintaining a shred of decorum in public life, we can only hope that neither of these billionaires invokes the American Dream in their speeches. Implicitly, however, they unavoidably will.

The dream can only be fulfilled if the fabulously poor consent to be the flipside of the fabulously wealthy. They have to be equally helpless fetishists who covet stuff and never have a dream worthy of the name in their entire earthbound existence. Thus, the person with nothing who, despite the unlikelihood that they will ever have anything, dreams of possessing everything, stays motivated. Why make do with the big illusion that you can one day be comfortably off, when you can have the even bigger illusion that you can be fabulously wealthy? Dream big or don’t dream at all. This happens routinely on Instagram. Oneiric penury is every American’s birth right. By the end of the process, the uninhibited vulgarity of the rich will have been redistributed across an entire society and they’ll all look about as cheerful as a recent self-portrait by Cindy Sherman.

Of course, another dream has always been possible, though it was pretty much extirpated by the rampant ethics of Protestant white men. When Henry David Thoreau chose spartan simplicity and communing with nature over patriotic, Godfearing wealth creation, he was really living the Unamerican Dream. It was very transcendental, and for most of his contemporaries the novelty of bucolic self-isolation would have begun to pall after the first half hour. Americans would find his lifestyle a lot easier these days, however. As long as the hut had a signal, they could keep up with their friends on Snapchat and get limitless quantities of merch from Amazon.

While the American Dream is about to fulfil its manifest destiny in the north, in Brazil it is still a work in progress. It must be dispiriting to see so much wilderness yet to be tamed, so many layabouts still powdering their noses without paying a cent for the privilege and making like they own the place, but where there’s a will.

As long ago as 1998, Jair Bolsonaro declared it was a shame the Brazilian cavalry hadn’t been as efficient as the (North) Americans “who exterminated the Indians.” Twenty years on, he is the head of state, which explains why Raoni Metuktire, a venerated leader of the indigenous tribes, has returned to the fray at the grand old age of ninety. “I have seen many presidents come and go,” he says, “but none spoke so badly of indigenous people or threatened us and the forest like this. Since he [Bolsonaro] became president, he has been the worst for us.”

Nobody swinging in their hammock, however spiritually attuned they might be, is safe from what’s coming. Gold mining, tree felling, road building, dam construction, cattle grazing – there are so many wonderfully efficient ways of fulfilling the American Dream, at the expense, as ever, of the Amerindian one.

Nobody swinging in their hammock, however spiritually attuned they might be, is safe from what’s coming. Gold mining, tree felling, road building, dam construction, cattle grazing – there are so many wonderfully efficient ways of fulfilling the American Dream, at the expense, as ever, of the Amerindian one.